What makes one city different from another? Some of it is the geography, the economy, or the buildings. But a big chunk of it is culture.

Every city has its own culture. A journalist recently interviewed me about Indianapolis and asked about some of the things that make that city’s culture distinct. I’m reposting ten of my observations here. Keep in mind that many of these points are relative, not absolute. They are comparisons versus what I see in other cities.

1. Indianapolis has a very open social structure. Many cities have very insular cultures that are difficult to penetrate. The Midwest river cities like Cincinnati, Louisville, and St. Louis are like this. If you weren’t born there, in a sense you’re always something of an outsider. I’ve also heard reports of similar things about Cleveland, where people who come there have trouble making new friends and connections. The stereotype of some Southern cities is that who your daddy was, etc. matters a lot.

In Indy, outsiders can move to the city and rapidly make friends and contacts, and to get integrated into civic networks. Columbus, Ohio is similar I’m told. I speculate that these cities have a more open orientation because they are state capitals. They frequently have new players circulating in and out, and this opens up the social networks considerably.

A newcomer is likely to have a much better time of it in Indianapolis than most other Midwest cities.

2. The social life of Indianapolis happens in back yards. This was an observation made some time ago by local cultural commentator David Hoppe. It’s dead on. In a city like New York or Chicago, there’s a palpable sense of bustling street life. This is largely absent in Indianapolis. If you operate on the assumption that this is the One True Way cities should function, Indy looks bad. But in reality the history and even built environment of Indy simply created different forms of social life. Different doesn’t mean worse.

People in NYC have tiny apartments, so of course they want to be out and meet people out. People in Indy mostly have single family homes, and so people can gather inside and in back yards. This produces things like Sunday night dinners and porch parties. In my experience, this produces many more useful “collisions” than the merely physical ones you’re likely to have on the street in Chicago.

3. A bimodal distribution of quality. Indianapolis has a “barbell” shaped quality curve. There’s a lot of stuff that’s pretty bad, but some things that are truly excellent. So, for example, the design of the average street in Indianapolis is terrible, but Monument Circle is one of the world’s great urban spaces. This contrasts with say Columbus, Ohio, where the vast majority of things are solid but relatively few stand out as terrible or exceptional. Interestingly, Nassim Taleb recommends barbell strategies. This may be one reason why Indy has the best small city tech scene in the Midwest.

4. An excessive preference for the pragmatic. This is a common Midwest trait. Again, I’m writing a future magazine column about this and its downsides. But for now note that the Midwest tends to actively discourage ambitious undertakings and the pursuit of excellence. This can produce a stifling environment for people who want to dream big and care about doing things right. Indy is certainly far better than the rest of Indiana on this, but it’s still present.

Looking at Indy’s barbell quality distribution, it’s clear the community gives itself permission to do A+ level work in certain areas: sports hosting, Monument Circle, etc. But I’ve yet to crack the code on what the characteristics of these are that made them acceptable while so many others were not.

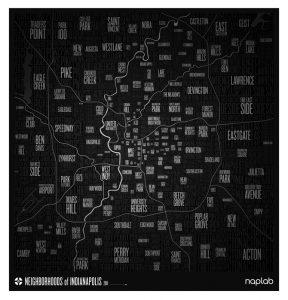

5. A weak sense of neighborhood identity. Cities like Chicago and Cincinnati are deeply steeped in a sense of neighborhood. They have strongly delineated, long-standing neighborhood areas people strongly feel themselves to be part of. Like Detroit, Indy has always been more about what side of town you live on than what neighborhood you live in. There were some exceptions to this, but the norm has been a weak sense of neighborhood identity. Unigov, where the city took in a lot of suburban and rural areas in a city-county merger, doubtlessly contributed to this, but I suspect it far predates that.

One reason some friends and I started the Naplab Indianapolis Neighborhood Map project was to start strengthening a sense of neighborhood identity.

6. Low cultural differentiation vs. the state. People who live in Indianapolis are Hoosiers and think of themselves that way. There’s historically been little sense of urban identity apart from the state. Chicago is like a different planet from Illinois. People in Chicago think of themselves as Chicagoans first, and Illinoisans secondarily if at all. By contrast, in Indy people are Hoosiers first, residents of the city second. It’s telling that there isn’t even a commonly used word to refer to residents of Indianapolis. Indianapolitans anyone?

Also, the city is mostly a draw from the rest of the state, so it has a very Hoosier feel. In Chicago, there’s a Midwest feel because it draws from a regional catchment area. In Dallas, you meet people from everywhere.

This is one the urban progressives would probably like to dispute, but they are a relatively small tribe in the city.

7. Low institutional differentiation vs. the state. As the only big city in the state, the city’s major institutions are frequently pressed into double duty as statewide ones. There’s an Indiana Historical Society but no Indianapolis Historical Society. (Is Indianapolis the biggest city in the country without its own historical society?) The major state economic development groups like TechPoint are basically Indianapolis organizations that serve a statewide audience.

People in the rest of the state people feel the state and major institutions give too much focus to Indy. But again, in many cases these are de facto Indianapolis institutions doing double duty for the state. In many (most?) states there would be separate organizations for the major urban region and for the state. In Indiana, that’s not the case. (I’m not familiar with how others states with one major city like Georgia and Minnesota are set up. Are they similar?)

8. A strong civic but weak political culture. Indianapolis is known for having three top notch mayors in a row: Richard Lugar, Bill Hudnut, and Stephen Goldsmith. But in general mayoral leadership and city government have not been the drivers of change. I don’t know how Lugar operated as I was not around. Goldsmith seemed to have a strong mayoral agenda (e.g., outsourcing). But others relied more on a broader civic grouping of people – business, foundations, etc. to get things done.

I suspect most cities would claim their civic sector is strong. Chicago likes to boast of its corporate involvement, for example. But it’s also clear that Chicago likes to get things done through a powerful mayor in City Hall. In Chicago, if the mayor says Yes to you, you are probably golden. In Indy, however, that’s not the case.

It’s hard to describe how this works because frankly it’s very opaque. Civic initiatives are largely cooked up in the back room behind the scenes. There seems to be a big focus on consensus. Disputes are generally not aired in public. And there’s a very “go along to get along” civic ethic.

This has had a lot of benefits. First, while it generally takes longer for Indy to decide to do something than other cities, once the decision is made to go forward, it almost always happens. You don’t see things like Louisville arguing for 40 years over whether and where to build a bridge (which only got built because Mitch Daniels stepped in). You don’t see repeated failures to pass a light rail program, like in Kansas City. When Indy decides to do something, it has a very high success rate. (A critic might say some of these things should have failed and that success at doing something you never should have done in the first place is a Pyrrhic victory).

Secondly, there is long term continuity in civic initiatives. Rarely do things die when mayors change. The sports hosting strategy has gone back over 30 years, for example. While the current mayor didn’t strongly support the transit initiative developed under his predecessor of a different party, he didn’t stand in its way either. Contrast with how a new mayor came into Cincinnati and tried to pull the plug on a streetcar project. Or at the state level Chris Christie in New Jersey taking office and cancelling a rail tunnel project.

The downside is a very enfeebled and low capacity city bureaucracy. Also, some changes need to come from the political sector in order to have democratic legitimacy. This makes the Indianapolis system bad at solving certain kinds of civic challenges. It should be no surprise that the mayor-driven (i.e., politically driven) system of suburban Carmel, Indiana was better able to redesign infrastructure, for example.

Another downside is that it’s an extremely difficult environment for a civic entrepreneur to try to get things done. That’s where cultural fit comes in. If you don’t know how to navigate an opaque civic structure, accumulate political capital in that environment, etc. then you are going to fail to accomplish anything. This tends to reward insiders vs. outsiders. Though because of point #1, outsiders can become insiders fairly easily in Indianapolis, if they know how to play the game. Due to the nature of the civic structure, playing the game is likely to involve significant dilution of their ideas and compromises many people might find unpalatable.

9. A strong preference for local hires. Indianapolis might be the biggest city in the country that’s basically never hired a global starchitect to design a major civic structure. Now there are many negative things one might say about the starchitect trend, but this is still revealing of the local culture. There’s a strong preference to hire locally in most places, but it’s very high in Indianapolis and often very clearly trumps quality. In fact, an out of towner with high flying ideas is exactly the kind of person who is going to be resented by a significant faction of the local power structure, and probably not be long for this world.

10. You need to a guide to find the good stuff. Similar to point #2, you’re not just going to stumble into some famous place randomly, like you can in many cities. It’s a city where you need a guide to point you at the good stuff. For example, PRINTtEXT at 52nd and College is one of the best magazine stores in the entire world. I’m not exaggerating. But you’d never find it unless you were looking for it. There are all sorts of great things and great people in Indy, but they take time to find and get to know. In some cities the greatness is on the surface. In Indy, it’s in layers you need to dig up over time.

Aaron M. Renn is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a contributing editor of City Journal, and an economic development columnist for Governing magazine. He focuses on ways to help America’s cities thrive in an ever more complex, competitive, globalized, and diverse twenty-first century. During Renn’s 15-year career in management and technology consulting, he was a partner at Accenture and held several technology strategy roles and directed multimillion-dollar global technology implementations. He has contributed to The Guardian, Forbes.com, and numerous other publications. Renn holds a B.S. from Indiana University, where he coauthored an early social-networking platform in 1991.

Top photo: Daniel Schwen, CC BY-SA 4.0

Second photo: Monument Circle. Photo Credit: alexeatswhales, CC BY 2.0

Fourth photo: Indianapolis hosting the Super Bowl. Image via Shutterstock.

Fifth photo: Image via PRINTtEXT Instagram