Forget about all the perceived problems with the American higher education system, and ponder these two numbers: 12.8 million and 3.4 million.

The first is the estimate of Americans actively looking for work and unemployed. The second is the number of job openings in the U.S. as of the end of December, according to the Labor Department.

There are jobs to be had, and plenty of people to fill them – if only they had the right skills. But this is not yet another article on the nation’s well-documented skills mismatch (at least not directly). Rather, it’s on the educational component of this debate, which was recently brought to the surface in a new Georgetown study on the unemployment rates analyzed by students’ major field of study in college, and by columnist Virginia Postrel’s response to it for Bloomberg.

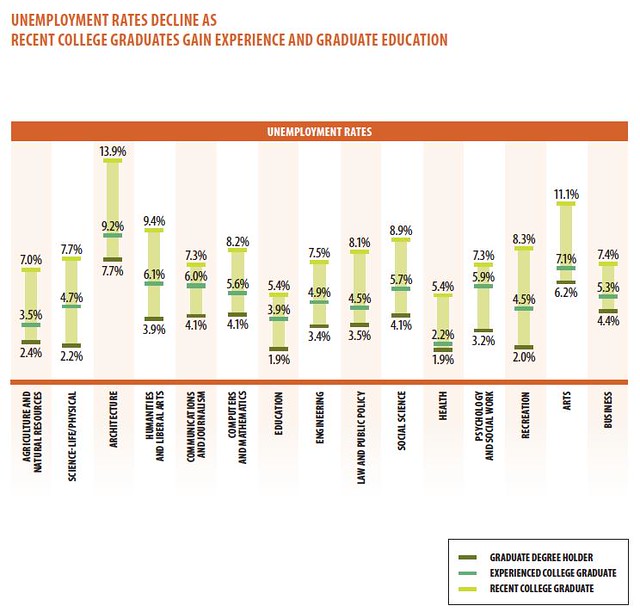

Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce, analyzing 2009-10 data on graduates from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, showed that the worst job prospects are for students coming out of architecture programs (13.9% unemployment), followed by arts (11.1%), humanities and liberal arts (9.4%), social science (8.9%), and law and public policy (8.1).

Postrel acknowledges some of Georgetown’s findings but goes right at those who think the US needs students to be more career-minded. Looking at national education stats, she argues most Americans are already choosing a college major based on the prospects of landing a job upon graduation. And if the supply of "practical" workers increases, Postrel warns, the quality of the workforce will deteriorate and wages will be lower.

“Contrary to what critics imagine,” she writes, “most Americans in fact go to college for what they believe to be ‘skill-based education.’ A quarter of them study business, by far the most popular field, and 16 percent major in one of the so-called Stem (science, technology, engineering and math) fields. Throw in economics, and you have nearly half of all graduates studying the only subjects such contemptuous pundits recognize as respectable.” Further, Postrel says those who argue for initiatives to push students in STEM fields – or away from liberal arts – disregard “the diversity and dynamism of the economy, in good times as well as bad.”

So what’s better? Would the U.S. be better off if more students took a broad-based liberal arts approach to their education, or should more be concerned with learning a specific trade or set of skills?

Postrel cited the National Center for Education Statistics’ report entitled "2008-09 Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study" (PDF here), which looked at graduates from the 2007-08 academic year. Two points should be made on this study: 1) the economy and employment prospects related to certain programs have changed drastically since 2007-08, and 2) the report includes only bachelor’s degree recipients.

With this in mind, EMSI tapped into the NCES database to get a more recent and thorough picture of the most popular programs areas for recent US grads. We looked at the total number of degrees given out in 2010 (the most recent year available from NCES) at the associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate level among major program categories.

Our analysis includes degrees at the four main postsecondary levels mentioned above, not certificates or postsecondary awards. We did this to better reflect graduates who have made a more-than-one-year investment in education and have therefore given their decision serious thought.

A few noteworthy items (see the full data here):

- Humanities majors account for 12% of graduates in the study Postrel used; according NCES’ latest data, which uses slightly different program classifications, 9.6% of all degrees came in liberal arts and sciences, general studies and humanities. One reason for the lower percentage could be that we included associate’s degrees (as well as bachelor’s, master, and doctorate degrees) in our analysis and the NCES study looked only at bachelor’s degree holders.

- Business, management, marketing and related programs make up the largest percentage of 2003 and 2010 degree recipients, just under 20% in both years. Postrel said a quarter of all degrees came in business (per the NCES study, it’s 23%).

- Health professions and related programs made the biggest jump among major program categories — from 9.2% of all degree recipients in 2003 to 12.7% in 2010–and now stands No. 2 overall. The biggest reason for this has been the dramatic increase in registered nursing/LPN and medical assistant degrees (see more on the supply of RNs).

- As a proportion of all degrees, computer and information sciences took the biggest hit — from 4.6% (127,088) in 2003 to 2.7% (94,730) in 2010.

These stats point to a few telling short-term shifts. Yes, a significant number of all degree recipients have moved toward skill-based education. But more striking is the decline in students choosing STEM majors as a share of all graduates. In 2003, 21% of degrees awarded in the U.S. were from STEM-related programs. In 2010, that percentage dipped to 19%.

Postrel would prefer students not be pigeonholed into going the skill-based route, even when it’s STEM-related. Yet it’s hard to ignore the illuminating data from Georgetown’s report: Recent grads in humanities and liberal arts have a 9.4% unemployment rate – lower than architecture, which has taken a beating with the construction downturn, but considerably higher than engineering (7.5%), business (7.4%), and especially health (5.4%).

So, to go back to the question posed earlier, our economy would seem to be better off – or, to put it another way, unemployment would most improve — if more students earned a skills-based education over a liberal arts degree. At least in the short term, that appears to be the best solution to get people back to work. But outside training for a few fields, there’s no automatic path to a job. Even some new registered nursing grads – with nursing once seen as a lock to find a job – are having a hard time finding employment. And EMSI and others have written about the souring job prospects for lawyers.

The Great Recession affected every industry in one way or another. Nonetheless, it’s worth repeating: There are 3.4 million jobs openings out there – 39% more than in June 2009. But in a sure sign that something is out of whack, hiring is only up 12% over that same time.

Flickr Photo by Jason Morrison: Ann Morrison gets her Masters of Science in Nursing, Pepper Pike, Ohio.

Joshua Wright is an editor at EMSI, an Idaho-based economics firm that provides data and analysis to workforce boards, economic development agencies, higher education institutions, and the private sector. He manages the EMSI blog and is a freelance journalist. Contact him here.