It is well known that home ownership has declined in the United States from the peak of the housing bubble. According to Current Population Survey data, the national home ownership rate fell 2.9 percentage points from the peak of the bubble (4th quarter 2004) to the third quarter of 2011.

It is less well understood, however, that the spurt in home ownership was, like the housing bubble, an aberration. Looking over the data from the 2010 census, it seems clear that since 2000 the actual decline was a much smaller: 0.8 percentage points from the 2000 census. In fact the current home ownership rate tracks fairly well with that of the post 1960 and the entire pre-bubble period.

The End of Home Ownership? Analysts such as Richard Florida suggest an end to the preference for home ownership, citing the losses from the bubble, which were, in fact, an aberration. Most recently, Xavier University’s Michael F. Ford wrote in the Washington Postabout home ownership having been driven to 69% by "guarantees" and "tax breaks," such as the mortgage interest deduction. He notes that this "spending spree" led to a loss of $6 trillion in US real estate value.

Ford does not mention the fact that home ownership had hovered between 60% and 65% for more than three decades before the bubble, without suffering any such losses. Nor does he mention the roles played by Fannie, Freddie and Frank (D-Massachusetts), along with others in Washington, or the related "drunken sailor" mortgage policies concocted by lenders and Wall Street that anyone familiar with credit should have known could only lead to disaster. This was obvious to many observers, although shockingly not to the Federal Reserve Board, as recent reports indicate .

There is no doubt that the "spending spree" led to the housing bust and triggered the Great Financial Crisis. However it was not the long-standing ownership support programs of the federal government that were primarily to blame. As late as the beginning of the decade, there was no bubble and the median multiple in major metropolitan areas averaged 2.9, within the maximum affordability rating of 3.0. The "spending spree" itself was a rational response to policies that turned housing into the equivalent of a speculative commodities market, with destructive results, in certain large markets. Critically the bubble did not appear in many others.

Speculation and the "Bubble States:" The extent to which speculation fueled house price increases is the subject of a recent Federal Reserve Bank of New York paper by Andrew Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Joseph Tracy and Wilbert van der Klaauw. The researchers examine investment, or speculation in real estate markets, during the housing bubble. Investors buy houses that they do not intend to live in for the purpose of making money. In normal times, this investment is principally for rental income or long term capital gains. However, in the highly charged housing markets that developed in some metropolitan areas, prices rose so rapidly, that "flipping" (short term ownership) became very profitable, at least for some.

Pointing out that "The recent financial crisis—the worst in eighty years—had its origins in the enormous increase and subsequent collapse in housing prices during the 2000s," the New York Fed researchers show that speculative activity was much greater in California, Florida, Arizona and Nevada (which they label the "bubble states") than elsewhere. My analysis indicates that two-thirds of the house value drop in the nation before the Lehman Brothers collapse (September 15, 2008) occurred in the four "bubble states." According to the researchers, this greater speculative activity in these markets made the market more instable because unlike owner-occupiers, investors are far more likely to default on mortgage loans.

Missing the Geography of Speculation (the Geography of "Smart Growth"): The New York Fed research, however, ignores the geography of speculation. Why was speculation was so much more rampant in the bubble states? There is no reason to believe that residents of California, Florida, Arizona or Nevada are any less interested in making money or, in general, any more greedy. Yet speculators largely stayed out of markets in high demand areas, such as Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston and Indianapolis. In fact, in large parts of the nation, there was little speculative activity. In these markets prices were not rising inordinately so speculators did not bother with them. Instead they focused on more volatile markets where prices were already rising strongly, further swelling local price increases.

The geography of speculation corresponds largely to the geography of excessive land use restrictions, which created the shortage of land for housing that drove the prices up in the four bubble states (Note). It is a fundamental principle of economics that prices tend to rise where desired goods are in short supply.

In California and Florida, restrictive land use policies (smart growth or growth management) created a shortage of land for new housing relative to demand. The largest metropolitan areas of Nevada (Las Vegas) and Arizona (Phoenix) are surrounded by government owned land that was auctioned for development at such a slow rate that prices rose by more than five times during the bubble.

Astonishingly, having missed the geography of speculation, the New York Fed researchers suggest that a solution is to regulate speculation. There is a much simpler answer, which Florida has already implemented which is to repeal the restrictive land use regulations, without which inordinately speculative profits cannot occur.

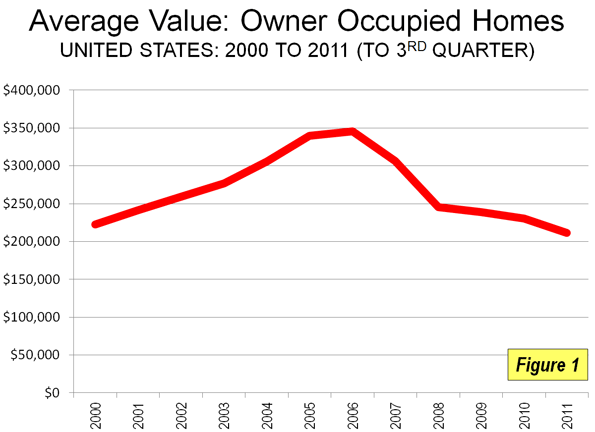

Meanwhile, as the speculators have been driven out of the market, and despite federal government efforts to prop-up the artificially high house prices, values have fallen to below 2000 levels for the first time (Figure 1). Based upon Federal Reserve Board and Census Bureau data, it is estimated that the average owner-occupied house value in 2011 (three quarters) has fallen to $211,000, which is down from a peak of approximately $345,000 in 2006 and $222,000 in 2000 (adjusted for inflation).

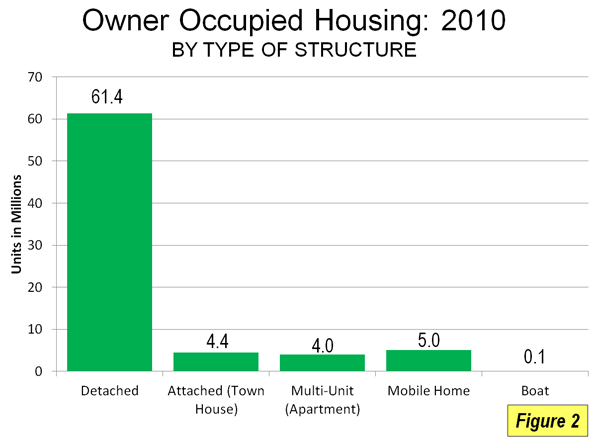

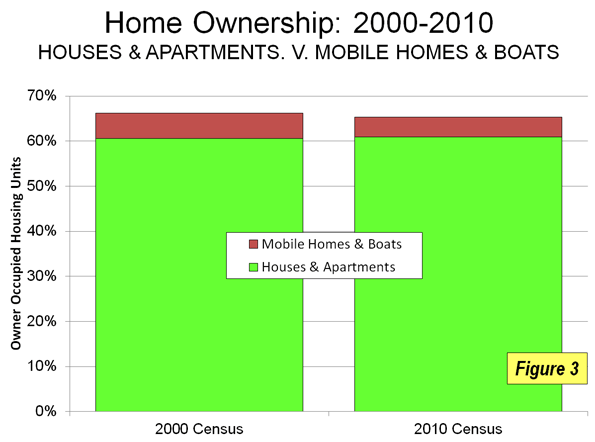

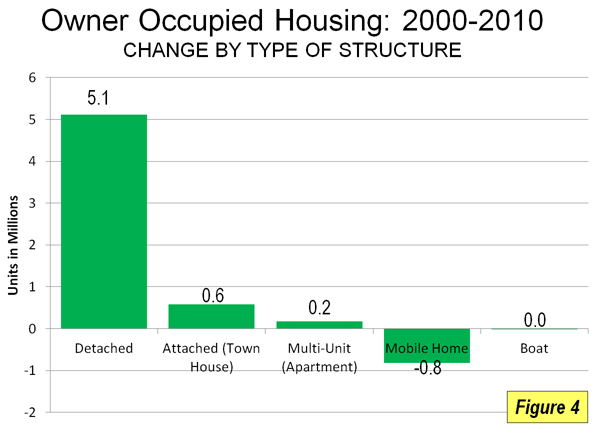

So is Ownership now doomed? Yet the home ownership naysayers have little to cheer. Yes, home ownership dropped in the last decade. However, all of the loss was in mobile homes and boats. Even so, the number of mobile home owners remained greater than home owners living in apartments, including condominiums (Figure 2). In fact there was a slight increase in the share of households owning their own homes, if mobile homes and boats are excluded (Figure 3), with a rise from 60.6% in 2000 to 60.9% in 2010.

There were 5,057,000 more home owners in 2010 than in 2000, and perhaps more surprisingly, 5,119,000 more home owners occupying detached housing. Detached, attached (town house) and apartment ownership each increased over the past decade (Figure 4). Contrary to new urbanist theoreticians, detached housing – not urban condos – overall accounted for the most housing growth, both owner-occupied and rentals.

Xavier’s Ford calls the American Dream of home ownership a myth and even goes so far as to suggest that home ownership is "more important to special interests than it is to most Americans." In fact, Ford’s interpretation is delusional. That home ownership continued its advance, however modestly, in the face of the worst economic downturn in 80 years, reveals the durability and, indeed the reality of home ownership as an American Dream.

Photo: Preventing speculation (New Development, Dallas-Fort Worth suburbs)

Note: Overall, the bubble states and other restrictively regulated metropolitan areas accounted for more than 90% of the pre-Lehman Brothers loss.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”