The No Child Left Behind Act became law in 2002. Among other things, it required standardized testing of students, beginning in 2003. The scores are used to evaluate the quality of the schools.

It sounds reasonable. Congress certainly thought so. It was co-authored in the Senate by Edward Kennedy (D-MA) and Judd Gregg (R-NH), while John Boehner (R-OH) and George Miller (D-CA) introduced it into the House. It passed both houses by huge bi-partisan majorities, 91-8 in the Senate and 384-45 in the House.

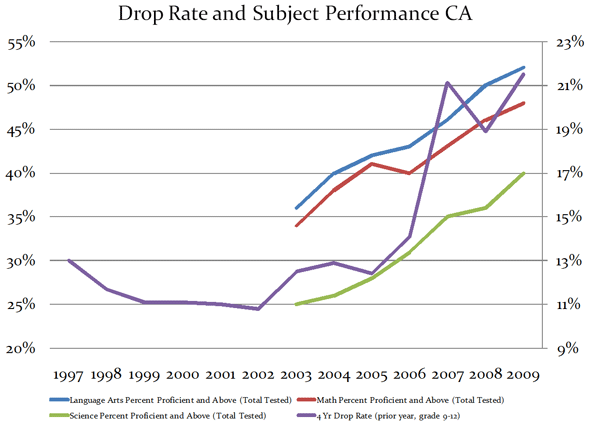

The Act’s passage also marked the low point in California’s High School dropout rate.

In 2002, California’s High School dropout rate had been declining for several years. After the act’s passage, the dropout rate trend experienced an unprecedented reversal. What had been a declining trend became an increasing trend, one that continues today. After bottoming out at less than 11 percent in 2002, California’s High School dropout rate is now approaching 22 percent.

The costs of dropouts are enormous, both for the students who leave school and for society. A person without a High School education is economically crippled. For all but the very exceptional few, dropping out of High School is a sentence to a lifetime of poverty and drudgery. For many dropouts, a lifetime of poverty and drudgery is the best possible outcome. Far too many will be involved in drug abuse, dysfunctional or violent relationships, teenage pregnancies, and crime.

The costs to society are large. They include losses to crime, and the direct costs of subsidies, social programs, healthcare, prisons, and law enforcement. Those costs may be exceeded by the dropout’s output deficiency, that is, the difference between what the dropout would have produced with a decent education and what he or she actually produces.

One way to improve standardized test scores is to increase the retention of tested topics by the students. An easier way is to prohibit students who would perform poorly from taking the test. Since all students have to take the test, this means converting poorly-performing students into non-students, letting them drop out.

It looks to me like California’s educational establishment has opted for the easy way.

On the chart below, the purple line shows California’s dropout rate from 1997 through 2009; you can see the percentages on the right-hand side of the chart. The other lines show the percentage — on the left side of the chart — of California’s students who passed the standardized tests for Math, Language, and Science. California’s passing percentage in each field has increased lockstep as dropouts increased.

It is worse than that, though. The percentage of students passing the standardized tests has increased by about 15 percent, on average, while the percentage of students dropping out has just about doubled. That’s an extraordinarily expensive improvement.

Did the schools follow this strategy deliberately? You can’t rule it out. People react to incentives, and the Act provides an incentive to abandon those who will likely perform poorly on the tests. Teachers will probably object to that, but we have no reason to believe that they should somehow be different that most people and ignore the incentives. Besides, we’ve already seen examples of teachers and administrators cheating on these tests.

Teachers assert that the solution to all of No Child Left Behind problems is to abandon it. The other solution, of course, is to fix the incentives. The way to do that would be to assign the schools a huge financial penalty for dropouts. Teachers and administrators would scream. They would tell us that dropouts result from problems at home and socioeconomic conditions.

No doubt, many students have terrible home conditions that put these children at a huge disadvantage, but those are exactly the children that we should be giving the most attention. A lousy home environment doesn’t explain the sudden increase in dropouts. These issues have been with us for a very long time. I took my first college economics class, The Economics of Poverty, in the 1969-1970 school year. There is nothing about poverty today that we didn’t discuss in that class, except that the returns to education have increased dramatically since then.

Failure to educate disadvantaged children guarantees that the perverse cycle of poverty and despair is perpetuated. Providing them with quality education, even with the active resistance of family, friends, culture, and the students themselves, is the only way to provide them with even the minimum hope for the upward mobility that government-provided education implicitly promises.

Abandoning our least advantaged children is unconscionable. If we are to have an egalitarian and merit-based society, we must reduce the dropout rate. The way to ensure that no one is abandoned is to penalize the school for dropouts. It sounds harsh, but we owe it to the students, and we owe it to ourselves.

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org

Flickr Photo by kerryj.com: “On national standardised testing, from a brilliant educator in Western Australia – a student’s view of national summative assessments”.