This is an excerpt from "Enterprising States: Creating Jobs, Economic Development, and Prosperity in Challenging Times" authored by Praxis Strategy Group and Joel Kotkin. The entire report is available at the National Chamber Foundation website, including highlights of top performing states and profiles of each state’s economic development efforts.

Read the full report.

Read part one in this series.

America has the world’s largest economy, the world’s leading universities, the most robust entrepreneurial culture and many of its biggest companies—yet many see this as a diminishing advantage.31 Stagnation, many predict, will extend into the foreseeable future because the economy’s low-hanging fruit has disappeared and so the pace of innovation has slowed; by this argument we are now on a “technological plateau” that will make further growth challenging.32 The United States remains a leader in global innovation, but better-funded, higher-performing hubs of innovation are emerging among determined competitors, notably China.

In contrast, we believe America’s prospects for competing with other countries are better than commonly assumed, and we are convinced that our strategy for the future is unlikely to be found elsewhere. Unlike our major competitors, we enjoy a huge base of natural resources—such as food and energy—which are likely to become ever more in demand as countries like China and India grow their economies. Most important of all, the United States, particularly in contrast with Europe and East Asia, enjoys relatively youthful demographics, promising an expanding workforce, new consumers and a new flood of entrepreneurs.

Yet our demographics and resources require intelligent policies that fit our particular situations. As a young country, we will have to find employment for an additional 20 million Americans in this decade. Slow growth, which could be accommodated in rapidly aging Japan or Germany, is not an option for the United States. We will also need to harness all forms of energy, from renewables to fossil fuels. Today, half of our trade deficit consists of energy, and yet we have the oil and gas resources to supply the vast majority of our needs. As we invest in renewables for the long run, the country needs to use the resources that are readily available in order to reduce the deficit and spark job growth.

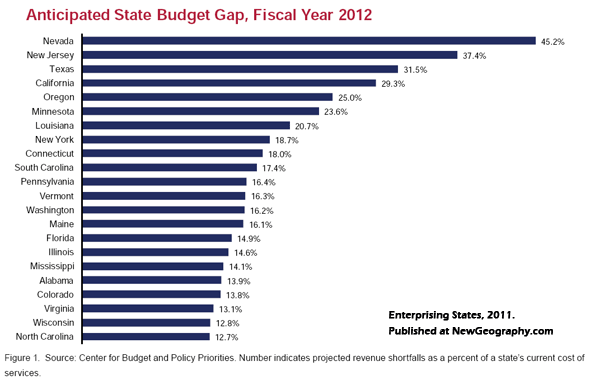

Our ability to compete, particularly on the state level, could be compromised by an inability to address our budgetary challenges. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, states are struggling with budget shortfalls for fiscal 2012 that add up to $112 billion. The most recent Fiscal Survey of the States anticipates considerably more financial stress in the states as the substantial funding made available by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 will no longer be available.

Most states have already taken actions to streamline and downsize government to meet the new economic realities. This has proven to be challenging given the increased demand for state services during the national recession. Surely, more redesign, streamlining and reform is on the way. To recoup lost revenue, states have taken such actions as eliminating tax exemptions, broadening the tax base, and in some cases increasing rates as well as raising a number of fees. Low tax rates by themselves are not a silver bullet for growth, but it has become clear that outdated state tax systems can undercut economic vitality.

States are the fulcrum of change in key areas of education, infrastructure, energy, innovation and skills training—something that was confirmed on many fronts in the first Enterprising States study. States and localities are far better positioned than the federal government to foster strategic investment, regulations, taxes and incentives that encourage private sector prosperity. In large part, this is because they are more responsive to local conditions.

Equally important, a diversified portfolio of opportunity agendas implemented by the individual states will go a long way toward renewing growth and prosperity in the national economy.

New Era of Leadership by the States?

As the 2010 Enterprising States study was being completed, the states were implementing sweeping changes to deal with a growing number of challenges. Since then twenty-nine new governors have started their terms. Governors of every state, along with their legislative counterparts, are taking steps to grow their states’ economies, create jobs and compete globally. They want to help businesses prosper, to produce an educated and skilled workforce, and to provide other essential services and infrastructure that foster the entrepreneurship and innovation that will lead to greater productivity and competitiveness.

The dramatic shortage of job opportunities has driven up the unemployment rate, pushed a large number of workers into part-time jobs, increased underemployment problems, and reduced the number of people who were expected to be active participants in the labor force. There is universal agreement that we need policies and programs that create jobs now, alongside investments to lay the foundations for long-term economic growth. “To keep the American dream of widely shared prosperity alive,” one commentator has argued, “we need to choose entrepreneurship and competition over the vested interests of the status quo.”

Restoring confidence in the economy by creating a meaningful and compelling plan for moving forward is a top priority for elected officials as well as leaders from business, education, and labor groups throughout the country.

There is also a stark recognition among the states that solving their fiscal problems is directly connected to creating an economic climate that will foster job creation. Any state with a budget tilting towards insolvency is in a weak position to make and maintain investments in its workforce and economic infrastructure. A state’s fiscal health also has immediate consequences by affecting its credit rating and, thereby, the cost of borrowing money. Unfunded pension obligations, viewed historically as soft debt, are now being considered together with the total value of state bonds to come up with a credit rating.

Many governors and state legislatures are attempting to strike a balance between budget cuts that could hold back the recovery by putting more people out of work, and spending cuts and government reforms that would create a more business-friendly environment, leading to greater business confidence, private-sector investment and job creation. How this balance is achieved depends on each state’s unique set of circumstances and available assets. Moreover, at their core, these debates reflect the fundamental tensions between the two major visions of American progress, namely: creating equality of condition by boosting wages, improving working conditions, and guaranteeing basic services, and creating equality of opportunity, by creating the conditions whereby individuals can elevate themselves through industry, perseverance, talent, and righteous behavior.

As noted in The Economist, private capital is mobile and it goes where government works. So while political considerations and ideological rationalizations certainly do influence the mix of austerity measures and public investments, the real opportunity today is for states to redesign government for the 21st century. That means cutting programs that do not spur economic growth and shifting resources, where possible, to those existing or planned programs that will.

While spending cuts will help control deficient budgets, so will increased revenue brought by economic growth. As states enact budget austerity measures, what job creation initiatives are surviving or receiving increased investment? What are the new priorities for job creation? How are states balancing cuts with critical job-creating initiatives that will stimulate innovation, build infrastructure, provide skills training, and unleash the dynamism of small business?

Job-Centric States Are Redesigning Government and Investing in Opportunity

Determining where to cut and where to invest40 is the central challenge of the day. States must carry out short-term strategies to jump-start and/or sustain an as-of-yet lackluster recovery, and cut costs to make state government more efficient and to avoid financial calamity. Simultaneously, though, they must craft and invest in innovations and structural solutions that will foster long-term economic growth while reining in taxes and regulations that stifle job creation.

In most states, revenues remain stubbornly down from where they were before the recession, and job growth is proving to be more elusive than in most previous recoveries. The strategies now being planned or undertaken by each state are based on their unique sets of interests, resources and capabilities, aligned with the opportunities that they see on the horizon and believe are conceivably within their grasp. Yet all states “will likely need a new network of market-oriented, private-sector-leveraging, performance-driven institutions”41 to restore and revitalize their economies.

The 2011 Enterprising States study highlights state-driven initiatives to 1) redesign government, including measures to deal with excessive debt levels that inhibit economic growth and job creation, and 2) forward-looking, enterprise-friendly initiatives whose primary goal is to create the conditions for job creation and future prosperity.

The policy initiatives and programmatic efforts are related to the five policy areas that were included in the original Enterprising States report.

- Entrepreneurship and Innovation

- Exports, International Trade and Foreign Direct Investment

- Workforce Development and Training

- Infrastructure

- Taxes and Regulation

What’s different in 2011 and for the foreseeable future is that for many states the imperative for change is real. The choice is simple. To remain a job-creating, fiscally robust economy, states will either change on their own or change will continue to be forced upon them.

Investing In Opportunity

States are taking a hard look at making investments in and implementing initiatives to create and sustain high-growth, higher-wage, 21st century industries.States play a key role in the higher education landscape, so there is considerable support for and investment in programs that educate the future talent pool and foster collaboration between business, education and government on science and technology, technology transfer and entrepreneurial programs. As states evaluate their return on investment, performance-based funding has become a best practice for aligning colleges and universities as partners in workforce preparation and sources of opportunity, growth, and competitive advantage.

High-growth start-ups are the best generators of new jobs, accounting for nearly all net job creation in America in the last twenty-plus years. They are also the firms most likely to raise productivity, a basis for economic growth. They also create jobs that did not previously exist, and solve problems in a way that makes a difference in people’s lives.

States have stepped up their efforts to help companies scale up and grow in order to capture growing domestic and international markets. A number of states have established or expanded seed and growth-stage financing funds. Some have implemented economic gardening programs deliberately designed to focus on expanding existing second-stage companies that have viable growth opportunities. Several states have undertaken initiatives to fix deficiencies in the market that inhibit private-sector investment and entrepreneurial activity. Tax credits for angel investors and state-backed venture capital funds are just two examples.

Companies with a global reach that bring together multiple technologies or complex expertise—such as advanced manufacturing, investment banking, construction and engineering, and natural resources—are likely to drive the nation’s global competitiveness in the next few years, along with more focused technology companies that are part of complex virtual networks.44 For that reason, several states are implementing, and having considerable success with, programs to help companies expand into global markets by assisting in the development of a customized international growth plan. And, some states have made significant headway using focused and purposeful strategies to attract foreign direct investment.

Public-private partnerships and privatization initiatives for economic development and the provision of infrastructure are proliferating throughout the states. Building funds and bonding programs that involve private-sector investors are now widely used to construct specialized facilities for research, demonstration, and technology transfer in key economic sectors. Building on the lessons of the past, states have become considerably more adept at avoiding what Robert Fogel has called “hothouse capitalism,” in which government assumes much of the risk while private contractors and financiers take the profit.

While unemployment remains high, many currently available jobs go unfilled. America faces a shortfall of almost two million technical and analytical workers in the coming years, a situation that stands to thwart economic growth.45 Painfully cognizant of this dilemma, many states are establishing workforce training and development programs that address structural unemployment problems and the mismatch between available jobs and the skills of the existing workforce. The goal is to align training and academic programs with in-demand regional occupations, and to add greater flexibility to workforce training programs that have left some re-trainable individuals slipping through the cracks.

Forward-looking states are modernizing their education and workforce training initiatives by developing people-focused approaches that help and train workers in navigating their careers, provide assistance for entrepreneurs, make lifelong learning loans, and offer wage insurance plans. The goal is to empower people to find better jobs and/or to create new ones. Plainly, making America more globally competitive is vital, but the increasingly obvious gap in our economic discussions is an agenda for making Americans more personally competitive. In this view, forging a new economics for the Individual Age will require rethinking our economy from the bottom up in order to realize future growth and prosperity.

Finally, because energy issues, both current and future, have become such critical factors in business and for economic growth, states are getting serious about policies, initiatives and investments to provide clean, secure, safe and affordable energy tailored to regional, state and local resources. These include renewable energy standards, investments in research, development and commercialization of energy technologies and processes, and the establishment of new financing authorities to build the infrastructure that will extract and transport energy to the places where it will fuel new growth.

Redesigning Government

The fiscal situation of many states has caused them to reconsider the level of services they are providing and, certainly, the way that they deliver them. According to the Government Accountability Office, “Because most state and local governments are required to balance their operating budgets, the declining fiscal conditions shown in our simulations suggest the fiscal pressures the sector faces and foreshadow the extent to which these governments will need to make substantial policy changes to avoid growing fiscal imbalances.”

In The Price of Government: Getting the Results We Need in an Age of Permanent Fiscal Crisis, David Osborne and Peter Hutchinson contend that Industrial Age government is just not up to the tasks and challenges at hand. Centralized bureaucracies, hierarchical management, rules and regulations, standardized services, command-and-control methods, and public monopolies are simply not aligned to Information Age realities. Today, government must be restructured and prepared for rapid change, global competition, the pervasive use of information technologies, and a public that expects quality and has lots of choices.

The keys, according to Osborne and Hutchinson, are to 1) get rid of low-value spending, 2) move money into higher-value, more cost-effective strategies and programs and 3) motivate all managers to find better, cheaper ways to deliver results. In sum, government needs to provide incentives, expect accountability, and allow the freedom to innovate.48

Government redesign efforts that are now underway or in the planning stages often follow the simple guidelines outlined above. Yet various approaches are now being used by state governments, including:

- Consolidation, reorganization, or elimination of agencies, boards and commissions.

- Regionalization of governance to decentralize decision-making and to customize and align service delivery with local circumstances.

- Streamlining and modernizing bureaucratic processes to increase productivity and improve service delivery, often by deploying services online.

- Experimenting with charter agencies that commit to producing measurable benefits and to saving money—either by reducing expenditures or increasing revenues—in exchange for greater authority and flexibility.

Steps to curb spending and reform taxation in the states have varied widely. States with the most serious fiscal problems are laying off workers, imposing hiring freezes, reducing spending for education and health care and ending or curtailing social services. Aid to local governments has been cut. For many states, current obligations for public pension funds and health insurance costs are unaffordable and future obligations represent a

looming financial disaster. Cuts, concessions and larger contributions from employees are now a necessary part of balancing the state’s checkbook.

Taxes and tax policies vary considerably among the states. To make up for lost revenues, most states have taken such actions as eliminating tax exemptions, broadening tax bases, and in some cases increasing rates as well as raising a number of fees. States have enacted increases in all of the major taxes they levy, including personal income taxes, general sales taxes, business taxes, and excise taxes. However, many states did reduce business taxes with new credits or expanded existing credits to encourage investment and growth in targeted industries.

Uncertainty, above all, is the antagonist of growth, investment, and job creation. States that cannot rid themselves of onerous DURT49 (delays, uncertainty, regulations and taxes) are in peril of putting the heaviest burdens on new and small businesses and on entrepreneurs, the real job creators in a growing economy. In a tight economy these considerations become more stringent for entrepreneurs and companies that are making economic decisions simply because the levels of uncertainty and the stakes are so much higher. Eliminating employment regulations and time-consuming processes that place unreasonable burdens on business can have a significant impact on job creation.

Moreover, the competitive identity of a state today relies increasingly on the degree to which the actions of the private, public and civic sectors are aligned with and corroborate the identity claimed or brand promise. A story must be backed up by actions: to simply proclaim an enterprise-friendly environment is no longer adequate.

States that are doing it right today are responsive and are taking a cooperative, supportive approach to dealing with new and existing companies. Their attitude and operating systems are customer-centric and their emphasis is on streamlining processes for obtaining permits, licenses, and titles.

Many state governments across the country are adopting a fast-track approach to achieving a better balance between the requirements of regulation and the need for new jobs and industry, so that that results have a higher priority than rules. This is the mindset that must guide the interface between government and business.

operating budgets, the declining fiscal conditions shown in our simulations suggest the fiscal pressures the sector faces and foreshadow the extent to which these governments will need to make substantial policy changes to avoid growing fiscal imbalances.”

In The Price of Government: Getting the Results We Need in an Age of Permanent Fiscal Crisis, David Osborne and Peter Hutchinson contend that Industrial Age government is just not up to the tasks and challenges at hand. Centralized bureaucracies, hierarchical management, rules and regulations, standardized services, command-and-control methods, and public monopolies are simply not aligned to Information Age realities. Today, government must be restructured and prepared for rapid change, global competition, the pervasive use of information technologies, and a public that expects quality and has lots of choices.

The keys, according to Osborne and Hutchinson, are to 1) get rid of low-value spending, 2) move money into higher-value, more cost-effective strategies and programs and 3) motivate all managers to find better, cheaper ways to deliver results. In sum, government needs to provide incentives, expect accountability, and allow the freedom to innovate.48

Government redesign efforts that are now underway or in the planning stages often follow the simple guidelines outlined above. Yet various approaches are now being used by state governments, including:

- Consolidation, reorganization, or elimination of • agencies, boards and commissions.

- Regionalization of governance to decentralize • decision-making and to customize and align service delivery with local circumstances.

- Streamlining and modernizing bureaucratic processes • to increase productivity and improve service delivery, often by deploying services online.

- Experimenting with charter agencies that commit • to producing measurable benefits and to saving money—either by reducing expenditures or increasing revenues—in exchange for greater authority and flexibility.

Steps to curb spending and reform taxation in the states have varied widely. States with the most serious fiscal problems are laying off workers, imposing hiring freezes, reducing spending for education and health care and ending or curtailing social services. Aid to local governments has been cut. For many states, current obligations for public pension funds and health insurance costs are unaffordable and future obligations represent a

looming financial disaster. Cuts, concessions and larger contributions from employees are now a necessary part of balancing the state’s checkbook.

Taxes and tax policies vary considerably among the states. To make up for lost revenues, most states have taken such actions as eliminating tax exemptions, broadening tax bases, and in some cases increasing rates as well as raising a number of fees. States have enacted increases in all of the major taxes they levy, including personal income taxes, general sales taxes, business taxes, and excise taxes. However, many states did reduce business taxes with new credits or expanded existing credits to encourage investment and growth in targeted industries.

Uncertainty, above all, is the antagonist of growth, investment, and job creation. States that cannot rid themselves of onerous DUR (delays, uncertainty, regulations and taxes) are in peril of putting the heaviest burdens on new and small businesses and on entrepreneurs, the real job creators in a growing economy. In a tight economy these considerations become more stringent for entrepreneurs and companies that are making economic decisions simply because the levels of uncertainty and the stakes are so much higher. Eliminating employment regulations and time-consuming processes that place unreasonable burdens on business can have a significant impact on job creation.

Moreover, the competitive identity of a state today relies increasingly on the degree to which the actions of the private, public and civic sectors are aligned with and corroborate the identity

States that are doing it right today are responsive and are taking a cooperative, supportive approach to dealing with new and existing companies. Their attitude and operating systems are customer-centric and their emphasis is on streamlining processes for obtaining permits, licenses, and titles.

Many state governments across the country are adopting a fast-track approach to achieving a better balance between the requirements of regulation and the need for new jobs and industry, so that that results have a higher priority than rules. This is the mindset that must guide the interface between government and business.

Read the full report, including highlights of top performing states and profiles of job creation efforts in all 50 states.

Praxis Strategy Group is an economic research, analysis, and strategic planning firm. Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and author of The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050