Sweden is often held up as a role model for those wishing to expand the size of government in the U.S. and other nations. The nation is seen as combining a large public sector with many attractive features, such as low crime rates, high life expectancy and a high degree of social cohesion.

But in actuality the success of the Swedish society lies not with the extent of its welfare state, but as the result of cultural and demographic factors as well as a favourable business environment throughout most of Sweden’s modern history.

First, it should be noted that Sweden experienced even higher rates of growth and impressive social outcomes well before the start of the Social Democratic era in 1936. Sweden was an impoverished nation before the 1870s, as evidenced by the massive emigration to the United States. As a capitalist system evolved out of the agrarian society, the country grew richer.

Property rights, free markets and the rule of law in combination with an increasingly well-educated workforce created an environment in which Sweden enjoyed an unprecedented period of sustained and rapid economic development. Famous Swedish companies like IKEA, Volvo, Tetra Pak and Alfa Laval were all founded during this period, aided by business friendly economic reforms and low taxes.

Between 1870 and 1936, the start of the Social Democratic Era, Sweden had the highest growth rate in the industrialized world. In contrast, between 1936 and 2008 the growth rate was merely the 18th highest of 28 industrialized nations.

Second, more attention needs to be paid to social and cultural factors. This reflects factors

such as the Lutheran work ethic and the cohesion of a largely homogeneous population with

particular social values. The perceived advantage of Swedes over other countries rose before

the rise of the welfare state. In 1950, before the rise of the high-tax welfare state, Swedes

lived 2.6 years longer than Americans. Today the difference is 2.7 years. Sweden’s lower

income inequality also stems back to at least the 1920s.

These same factors can be seen in the success of Swedes abroad. The approximately 4.4 million Americans with Swedish origins are considerably richer than the average American, as are other immigrant groups from Scandinavia. If Americans with Swedish ancestry would form their own country their per capita GDP would be $56,900, more than $10,000 above the earnings of the average American and 53 percent above the Swedish GDP level of $36 600.

A Scandinavian economist once stated to Milton Friedman: “In Scandinavia we have no poverty.” Milton Friedman replied, “That’s interesting, because in America among Scandinavians, we have no poverty either.” Indeed, the poverty rate for Americans with Swedish ancestry is only 6.7 percent, half the U.S. average. Economists Geranda Notten and Chris de Neubourg have calculated the poverty rate in Sweden using the American poverty threshold, finding it to be an identical 6.7 percent.

Critically, those Swedes who immigrated to the U.S., predominately in the 19th century, were anything but elite. Many were escaping poverty and famine. What has made Sweden uniquely successful is not the welfare state, as much as the hard-won Swedish stock of social capital.

Third, the recent strong performance of the Swedish economy has its roots in labor market and other reforms enacted by center-right governments. Perhaps least appreciated, Sweden has dramatically scaled back the size and scope of government starting in the 1990s, which spurred the recovery of the growth rate.

Indeed, modern Sweden’s success can be seen as more a shift away from the far left policy that predominated from the 1960s till the end of the century. During recent years Swedish policies have shifted strongly to the center-right, placing the once dominant Social Democrats in deep crisis.

An important explanation is that the Swedish electorate wishes to again strengthen the ethical norms that have been eroded during the high tax regime. The center-right government that took office in 2006 and was re-elected in 2010 has implemented stepwise and rather large tax reductions.

Few other nations demonstrate as clearly the phenomenal economic growth that results from adopting free-market economic policies. School vouchers have successfully been introduced, creating competition within the frame of public financing. Similar systems are increasingly being implemented also in other public programs, such as health care and elderly care. Another example is that the pension system has been partially privatized, giving citizens some control over their mandated retirement savings.

Where is Sweden headed?

Yet this is not to say Sweden can not go further into a free market direction. Although taxes have been lowered, research publication reveal they still impact to the level of entrepreneurship and crowding out private sector job creation. One study has for example shown that for each additional Swedish Kronor levied and spent by the government, the efficiency losses in the private sector can be as high as 1-3 additional Kronor.

One particular challenge lies with immigrants. In the past Sweden was highly successful in integrating immigrants. In 1950 the level of employment for foreign-born was 20 percent higher than the average citizen. In 2000 the level of employment was 30 percent lower for the foreign-born.

In 1968 foreign citizens living in Sweden had 22 percent higher income from work compared to those born in Sweden. In 1999 foreign citizens had 45 percent lower incomes. While racism had decreased significantly as time had passed, the situation of those born abroad in the labour market had worsened dramatically.

A government study has shown that in 1978 foreign born from outside the Nordic nations had an employment level that was only seven percent lower than ethnic Swedes. In 1995 the gap had expanded to 52 percent.

Looking forward, it’s clear that Sweden’s great advantages lie not in socialism, but in circumstances. In addition to its considerable human capital, Sweden has an abundance of natural resources, another that the nation was not involved in either of the worlds wars, which tore up other industrialized nations.

There remain many problems connected to the welfare state. Amongst others Jan Edling, former economist at the labor union LO which has close ties to the Social Democratic party, has discussed this high hidden unemployment and the connection to over-utilization of welfare systems. Around one fifth of the working age population in Sweden are supported by one form or another of government handouts rather than work.

The Swedish welfare state, of course, does create some social good, by for example providing relatively generous social security nets. But it is clearly not solely responsible for the low poverty and long lifespan in the nation.

Many in the United States and elsewhere who tend to see Sweden as a social democratic role model fail to understand the history and trajectory of Swedish society. Indeed, much of the success of Sweden, and other Scandinavian nations, relate to strong norms and entrepreneurship.

To be sure, Swedish society is not necessarily moving away from the idea of a welfare state, but continuous reforms implemented towards economic liberty have strengthened the society. The rise of government has been stopped and clearly reversed during the past years. Sweden is again returning to the free market policies which have served it so well in the past.

Nima Sanandaji, is President of the Swedish think-tank Captus.

Photo by Hector Melo A.

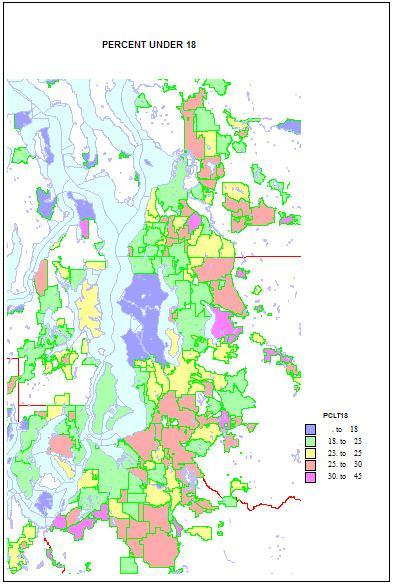

Higher shares of persons under 5 reveal areas of young families. The highest shares are in military bases and Latino towns in eastern Washington, but are quite high, over 12 percent, in the farthest suburban and exurban places around Seattle such as Duvall and Snoqualmie. They are lowest in retirement towns, on islands such as Vashon and Bainbridge, and in some college towns such as Pullman.

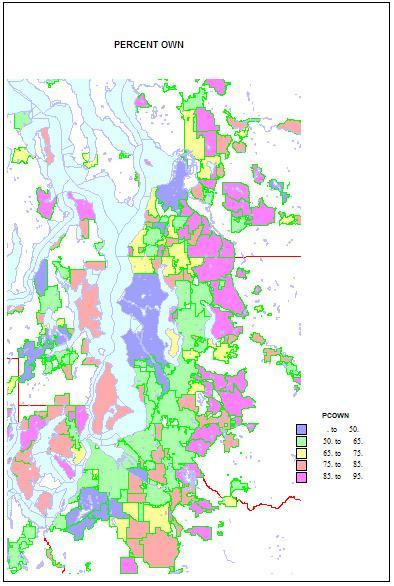

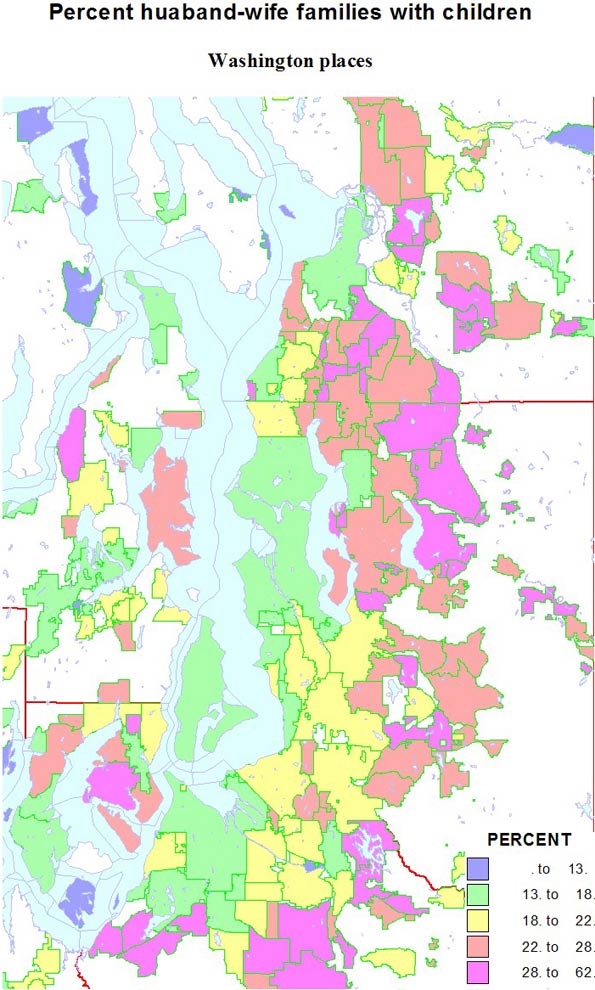

Higher shares of persons under 5 reveal areas of young families. The highest shares are in military bases and Latino towns in eastern Washington, but are quite high, over 12 percent, in the farthest suburban and exurban places around Seattle such as Duvall and Snoqualmie. They are lowest in retirement towns, on islands such as Vashon and Bainbridge, and in some college towns such as Pullman. Home ownership is related to both age and household types. Rates of home ownership are extremely high, in the 90s in newer and more affluent suburbs, with mainly single family homes; the rates are lowest on military bases, college towns, and in a few less affluent suburbs, such as Tukwila. As for the city of Seattle — which has indeed changed its character in a fundamental way — home ownership has dropped to a low of 48 percent. This shift helps us understand the cleavages in Seattle’s body politic, as a formerly very middle class city adjusts to an influx of singles, renters, and young people.

Home ownership is related to both age and household types. Rates of home ownership are extremely high, in the 90s in newer and more affluent suburbs, with mainly single family homes; the rates are lowest on military bases, college towns, and in a few less affluent suburbs, such as Tukwila. As for the city of Seattle — which has indeed changed its character in a fundamental way — home ownership has dropped to a low of 48 percent. This shift helps us understand the cleavages in Seattle’s body politic, as a formerly very middle class city adjusts to an influx of singles, renters, and young people.

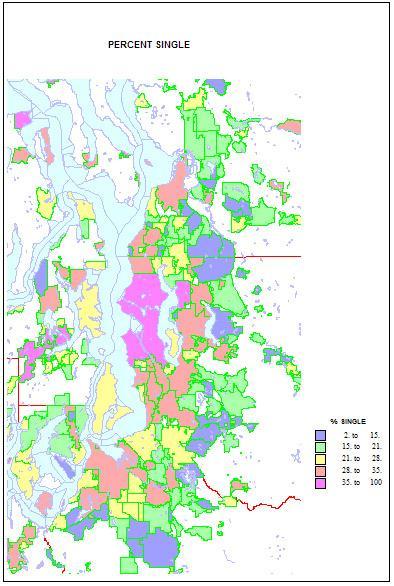

Conversely, singles are highest in two island towns, Friday Harbor and Langley, but Seattle is an extremely high 41 percent. Shares are lowest in the same new suburbs rich in families, as in Sammamish, at 11 percent. Shares of unmarried partners are a high 10 percent of households in Seattle, but are higher on Indian reservations and the cities of Hoquiam and Aberdeen. The share of single-parent households is also high on Indian reservations, in less affluent and more ethnic suburbs like Parkland and Bryn Mawr and Tukwila. It is lowest in the newer, family-filled far suburbs.

Conversely, singles are highest in two island towns, Friday Harbor and Langley, but Seattle is an extremely high 41 percent. Shares are lowest in the same new suburbs rich in families, as in Sammamish, at 11 percent. Shares of unmarried partners are a high 10 percent of households in Seattle, but are higher on Indian reservations and the cities of Hoquiam and Aberdeen. The share of single-parent households is also high on Indian reservations, in less affluent and more ethnic suburbs like Parkland and Bryn Mawr and Tukwila. It is lowest in the newer, family-filled far suburbs.