The state of New Jersey virtually defines suburbanization in the United States. New Jersey is not home to the core of any major metropolitan area but, major portions of the nation’s largest metropolitan area (New York) and the fifth largest metropolitan area (Philadelphia) are in the state (See map). These two metropolitan areas comprise 17 of the state’s 21 counties. Another county (Warren) is in the Allentown, Pennsylvania metropolitan area, while Atlantic (Atlantic City), Cumberland and Cape May are single-county metropolitan areas. No one, however, should make the mistake of imagining that New Jersey is wall to wall suburbanization. In the 2000 census, more than 60 percent of the state’s land area was rural, with urban areas (areas of continuous urban development) making up less than 40 percent of the state’s land area, while 94 percent of the 2000 population was urban (which includes suburban).

Map courtesy of Passaic Public Library

Map courtesy of Passaic Public Library

The recently released 2010 census data indicates that the dispersion of New Jersey population, which was underway by 1900 and continued apace in the last decade.

New Jersey’s Larger Municipalities: This is not to suggest that it was a bad decade for the larger municipalities in the state. However, the 20th century was not kind to New Jersey’s largest municipalities. At some point during the century, six municipalities reached a population of 100,000 or more. Four of these municipalities were near the city of New York and were eventually engulfed by its suburbanization (Newark, Jersey City, Paterson and Elizabeth). Another, Camden, was engulfed by Philadelphia’s expansion and the last, the state capital Trenton, is midway between the cores of the two metropolitan areas and has more recently become a part of the New York metropolitan area.

The new decade started out better for these municipalities. Newark, Jersey City, Elizabeth and Camden gained population between 2000 and 2010. However, even after the population gains, Newark’s population remains 165,000 (37 percent) below its 1930 peak. Jersey City remains 70,000 (22 percent) below its 1930 peak, despite the growth of a new financial district just across the Hudson River from lower Manhattan. Camden remains approximately 35,000 (37 percent) below its 1950 peak. Of the four municipalities gaining population, Camden did the best, adding 6.9 percent to its population, a full 50 percent above the statewide increase of 4.5 percent.

Paterson and Trenton posted small population losses. Trenton remains nearly 45,000 (33 percent) below its 1950 peak (Table 1).

| Table 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| New Jersey Municipalities Achieving 100,000 Population |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Census Population |

Peak |

| Municipality |

2000 |

2010 |

Change |

% Change |

Population |

Year |

| Newark |

273,946 |

277,140 |

3,194 |

1.2% |

442,337 |

1930 |

| Jersey City |

240,055 |

247,597 |

7,542 |

3.1% |

316,715 |

1930 |

| Paterson |

149,222 |

146,199 |

(3,023) |

-2.0% |

149,227 |

2000 |

| Elizabeth |

120,568 |

124,969 |

4,401 |

3.7% |

124,969 |

2010 |

| Trenton |

85,403 |

84,913 |

(490) |

-0.6% |

128,009 |

1950 |

| Camden |

78,672 |

84,136 |

5,464 |

6.9% |

124,555 |

1950 |

| Total |

947,866 |

964,954 |

17,088 |

1.8% |

1,285,812 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Balance of State |

7,466,484 |

7,826,940 |

360,456 |

4.8% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| New Jersey |

8,414,350 |

8,791,894 |

377,544 |

4.5% |

8,791,894 |

2010 |

Elizabeth and Paterson however have been far more successful in retaining their population than other older municipalities, both in New Jersey and around the nation. Both Elizabeth and Paterson have become majority Hispanic and have a sizeable African American community. They also have a large immigrant community. In Elizabeth, 45 percent of the population is foreign born, almost four times the national rate. Paterson has an immigrant population of 25 percent.

The Older Suburban Counties: Nonetheless, even with the modest population reversals in four of the five municipalities in the Philadelphia and New York metropolitan areas, their corresponding older suburban counties grew slower than the rest of the state in the 2000s. Combined, Camden, Essex, Hudson, Passaic and Union counties – fast growing suburbs of the early 1900s – grew at a rate of 1.6 percent, compared to the statewide growth rate of 4.5 percent, capturing 12 percent of the statewide growth. (Table 2).

| Table 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| New Jersey County Population Growth by Area |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Area |

2000 |

2010 |

Change |

% Change |

Share of Growth |

| 5 Older Suburban Counties |

2,923,130 |

2,969,617 |

46,487 |

1.6% |

12.3% |

| Balance of NY & Phila Metropolitan Counties |

4,887,467 |

5,184,873 |

297,406 |

6.1% |

78.8% |

| Outside NY & Phila Metropolitan Area |

603,753 |

637,404 |

33,651 |

5.6% |

8.9% |

| Total |

8,414,350 |

8,791,894 |

377,544 |

4.5% |

100.0% |

| Note: 5 Older Suburban Counties Include Camden, Essex, Hudson, Passaic and Union |

|

The Newer Suburban Counties: The bulk of New Jersey’s growth has taken place, as in the rest of the country, in more newly suburbanizing counties of the Philadelphia and New York metropolitan areas (Note 1). The growth rate in these counties was 6.0 percent, well above the statewide growth rate of 4.5 percent. Overall, the outer suburban counties accounted for 73 percent of the state’s population growth during the 2000s. The strongest growth was in Ocean County, which is at the furthest distance (fifty to one hundred miles) from New York City. Ocean County grew 13 percent, adding 66,000 people to its population, nearly one-fifth of the state population gain. Gloucester County, in the Philadelphia area also grew 13 percent, adding 33,000 to its population. Ocean and Gloucester accounted for more than one-quarter of New Jersey’s population growth. Only one other county added more than 50,000 people, Middlesex, which is adjacent to the New York City borough of Staten Island in New York, much of which is made up of postwar suburbanization.

Counties Outside the Large Metropolitan Areas: The counties outside the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan area, Atlantic, Cape May, Cumberland and Warren added 5.6 percent to their population and nine percent of the state’s population gain. The largest growth was in Atlantic County (8.7 percent) and Cumberland County (6.1 percent), both adjacent to counties of the Philadelphia metropolitan area. Cape May County had the largest population loss in the state, at 4.9 percent (Essex County, where Newark is located, lost 1.2 percent, the only other county to lose population).

Small Area Analysis: The dispersion of the population is also illustrated by "place" data, which includes incorporated municipalities (Note 2) and "census designated places."

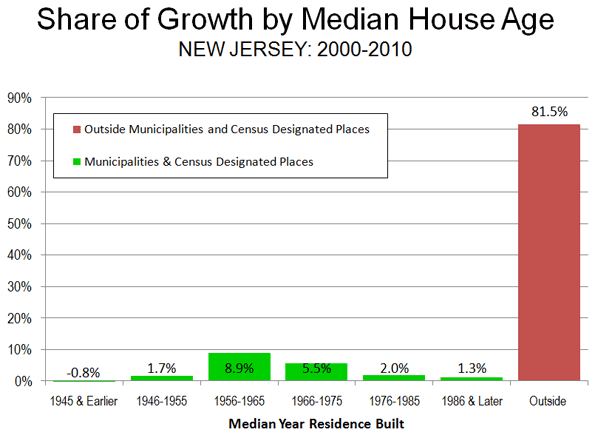

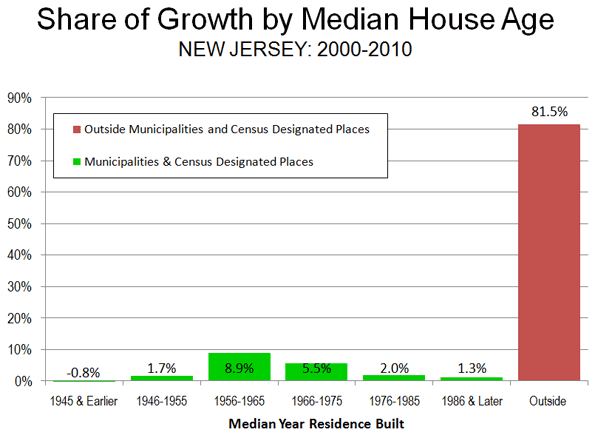

Generally, newer housing reflects the distance of suburbs from the urban core. Gaining a larger share of population growth, this demonstrates a primarily suburban, rather than urban core oriented, expansion. An analysis of the more than 500 places (municipalities and "census designated places") indicates that the greatest share of New Jersey’s growth is in new suburban areas.

Among places in which housing has a median construction date of 1945 or earlier, there was a 0.8 percent reduction in population. The growth rate then rises with each 10 year increment, reaching 4.0 percent in places with a median construction date of 1976 to 1985 and 11.1 percent for places with a median construction date of later (though this is the smallest category).

However, the growth in these places accounts for only 18.5 percent of the state’s population gain. The other 81.5 percent was outside the incorporated municipalities and the census designated places. This population is generally in the state’s townships, some of which are older (such as North Bergen or Woodbridge), but most of which are much newer. However, much of the growth in the townships was in newer areas, with 84 percent in areas with median construction dates of 1966 or later (Note 3)

Thus, all-metropolitan New Jersey is becoming more suburban, while older, major municipalities such as Newark, Jersey City and Camden are enjoying a welcome respite from their generally steep declines.

—

Note 1: These counties include Bergen, Burlington, Cumberland, Hunterdon, Mercer, Middlesex, Monmouth, Morris, Ocean, Salem, Somerset and Sussex.

Note 2: New Jersey township officials have been engaged with the Census Bureau in a dispute over whether New Jersey townships should be considered incorporated. This analysis uses the "non-incorporated" status as defined by the Census Bureau, without taking a position on the nature of the disagreement.

Note 3: The Census Bureau routinely makes changes to "census designated places" between censuses. As a result it is not possible to reconcile the township and place totals to the state total. There is a discrepancy of approximately 1.5 percent. This discrepancy is small enough to make the township figures generally reflective of the median construction dates.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life ”

”

Map courtesy of Passaic Public Library

Map courtesy of Passaic Public Library