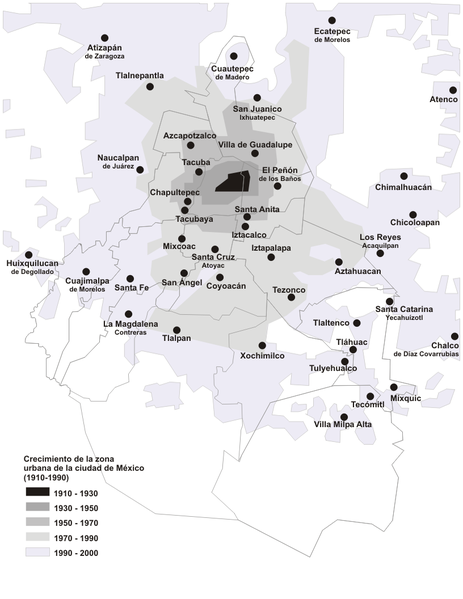

The last 60 years of urban growth in the Mexico City area should dispel any belief that suburban dispersion is principally an American phenomenon or even limited to the high income world. Over the last 60 years, all of the population growth in what is now called the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area and urban area has occurred outside the urban core (See Map). In this regard, the declining population in Mexico City urban core mirrors that of other urban cores, such as the city of Chicago, the city of Copenhagen, the city of Paris and nearly all other urban cores in the high income world.

Map: Valley of Mexico Urban Area: Northernmost Urbanization Excluded

A New Name: the Mexico City metropolitan area is one of only two out of the world’s more than 25 megacities (10 million or more population) that has adopted a name more reflective of geographical reality, shedding reference to the urban core, which is declining in influence virtually everywhere. The other name-changing metropolitan area is Jakarta where the name Jabotabek is an acronym composed of the beginning of four large municipality names. Mexico’s national statistics bureau, the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) has designated the Mexico City metropolitan area as the "Zona Metropolitana del Valle de México," which translates to the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area.

According to the broadest definition, the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area had a population of 21.4 million according to the 2010 census. The Valley of Mexico joins a lengthening list of metropolitan areas with more than 20 million people. No reliable world ranking of metropolitan areas is feasible, because of varying definitions by nations and other population estimating sources (Note: Metropolitan Ranking). It can be said with assurance that the world’s largest metropolitan area is Tokyo – Yokohama, with approximately 40 million people and perhaps even that Jabotabek ranks second at nearly 30 million people. Other metropolitan areas making legitimate claims to having more than 20 million people include Seoul, Sao Paulo, Mumbai, Delhi, Manila and New York (Note: New York).

The Valley of Mexico Urban Area

In the early 1980s, the Valley of Mexico was expected to become the world’s largest urban area. A number of factors worked to keep that from happening, such as a falling birthrate and the devastating earthquake of 1985, which slowed growth and the simple problems created by the unmanageable scale of the region. This led to greater decentralization both to peripheral parts of the Valley of Mexico as well to other Mexican states.

In 2010, the Valley of Mexico urban area had a population of 19.4 million people. The urban area is estimated to cover 780 square miles (2,020 square kilometers), for a population density of 25,000 per square mile (9,700 per square kilometer). This makes the Valley of Mexico urban area approximately one-fourth the density of Dhaka (Bangladesh), the densest urban area in the world and similar in density to the Cairo urban area. The Valley of Mexico is less than three times as dense as the Paris urban area and less than four times the density of North America’s most dense urban areas, Los Angeles and Toronto. The next edition of Demographia World Urban Areas: Population & Projections (current edition) will show the Valley of Mexico to be the world’s ninth largest urban area.

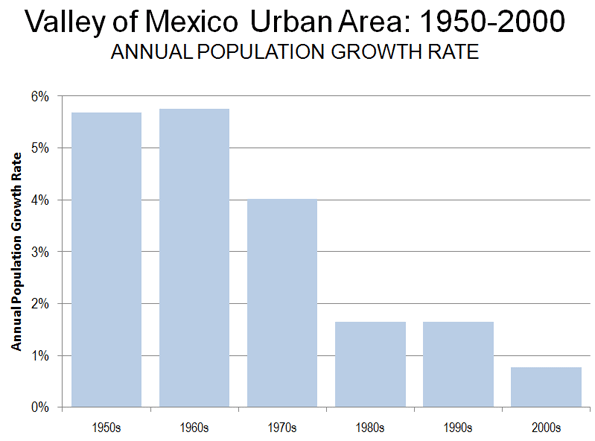

The key issue here is a population growth rate that has plummeted since 1950. In the 1950s and the 1960s, the Valley’s population growth exceeded 5.5% annually. The rate fell to 4.0% during the 1970s, and dropped to 1.6% in the 1980s and 1990s. By the 2000s, the annual population growth rate had fallen to 0.8% (Figure 1).

Urban Core: Former Mexico City: In 1950, the core “delegations” constituted Mexico City – Cuahtemoc, Miguel Higalgo, Venustiano Carranza and Benito Juarez had 2.23 million people out of the urban area’s 2.88 million. Mexico City covered a land area of 54 square miles (139 square kilometers). In 1970 the population rose to a peak of 2.85 million with a peak population density of 53,000 persons per square mile (20,500 per square kilometer). At this point a severe population decline began, with a drop of more than 1.1 million people to 1.68 million by 2005. This represented a 41 percent drop in population density, two 31,000 persons per square mile (12,000 persons per square kilometer). A modest increase to 1.73 million people occurred between 2005 and 2000 in the urban core.

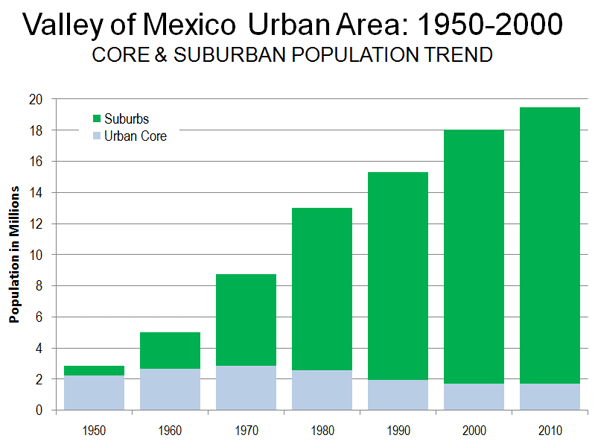

In 1950, the urban core accounted for 78 percent of the urban area population. By 2010 this figure had fallen to under nine percent (Figure 2).

The Suburbs: As of the 2010 census, more than 90 percent of the urban area population lives in what has historically been the suburbs. Since 1950, the urban core has lost 500,000 residents; while suburban areas have added more than 17 million. Thus, the suburbs have accounted for more than 100 percent of the growth in the urban area over the past 60 years (Figure 1). During the 1950s, the suburbs accounted for more than 80 percent of the growth and in each decade since that time the suburbs have been 95 percent or more of the growth.

In the earlier decades, the suburbs inside the Distrito Federal (but still outside the urban core) accounted for most of the growth, 93 percent during the 1950s and 53 percent during the 1960s. However from the 1970s to the present the growth has shifted to the more distant suburbs outside the Distrito Federal. These suburbs have captured at least 70 percent of the growth, including between 80 percent to 90 percent over the past two decades.

Valley of Mexico Metropolitan Area

The trend of continuing dispersion is evident in the metropolitan area trends. As defined in 2005, the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area included the 16 "delegations" (boroughs) of Mexico City (the Distrito Federal), and 60 municipalities (municipios), 59 of which are in the adjacent state of Mexico and the last of which is in the more northerly state of Hidalgo. In the late 2000s, another 28 municipalities in the state of Hidalgo were proposed for addition to the metropolitan area (and are included in this analysis).

The metropolitan area is divided into five parts, the urban core (pre-1994 Mexico City), the urban balance of the Distrito Federal, inner ring municipalities, which are adjacent to the Distrito Federal, the outer municipalities before the proposed expansion and the 28 municipalities in the state of Hidalgo.

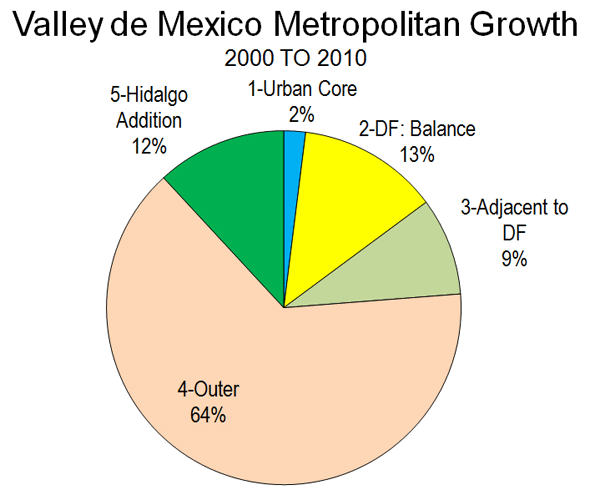

Between 2000 and 2010, the urban core of the former Mexico City added 38,000 people or two percent to its population but accounted for only two percent of total metropolitan area population growth. Thus, during the 2000s, suburbs (areas in the urban area outside the urban core) gained 98 percent of the population growth (Figure 3).

The vast majority of the growth took place either in the outer delegations – some 12 percent of growth –while the inner suburbs of the state of Mexico captured 9 percent of the growth. The "lion’s share" of the growth was in the outer suburbs of the states of Mexico and Hidalgo, at more than 75 percent.

Clearly, the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area is prime example of the suburbanization and reduced urban densities that have occurred virtually around the world.

| Valley del Mexico Population: 2000 to 2010 | |||||

| Geographical Sector | 2000 | 2010 | Increase | Rate | Share |

| Urban Core (Former Mexico City) | 1.692 | 1.730 | 0.038 | 2% | 2% |

| Balance of Distrito Federal | 6.913 | 7.143 | 0.230 | 3% | 13% |

| Distrito Federal | 8.605 | 8.873 | 0.268 | 3% | 15% |

| Inner Muncipalities | 6.061 | 6.232 | 0.171 | 3% | 10% |

| Outer Municipalities | 3.730 | 5.032 | 1.302 | 35% | 75% |

| Hidalgo Expansion | 0.993 | 1.240 | 0.248 | 25% | 14% |

| Total | 19.390 | 21.378 | 1.740 | 9% | 100% |

| In millions | |||||

——

Note: New York: according to US Census Bureau estimates from 2009, the New York metropolitan area had slightly less than 20 million people. However the Combined Statistical area (which includes the Connecticut suburbs) had a population of 22 million people. Because metropolitan areas are labor market areas, the extent of their transport systems is an important factor in delineation. In the case of New York, the extent of the highway and transit systems is sufficient to suggest the combined statistical area as more appropriate for international comparisons.

Note: Metropolitan Area Ranking: There is only one known research effort to consistently define and rank the world’s metropolitan areas. Richard L. Forstall (who ran the Rand McNally "Ranally" international metropolitan area program), Richard P. Green and James B. Pick, produced that list, which was limited to the top 15 in the world. This small number, in relation to more than 750 metropolitan areas in the world with more than 500,000 people illustrates both the difficulty of obtaining sufficient data and the complexity of the research.

Note: Pachuca de Sota: the entire urban area is within the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area.

Photo: Cathedral, Mexico City (by author)

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”