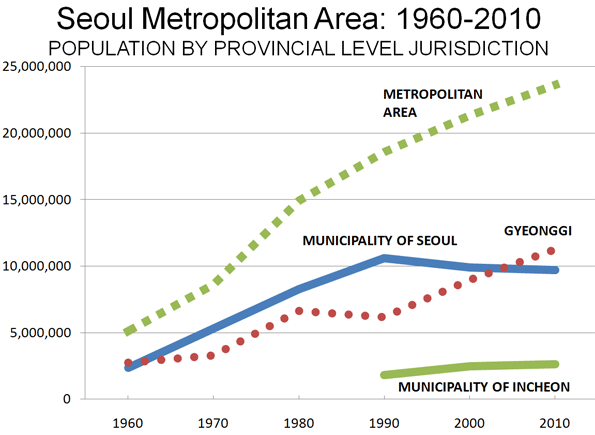

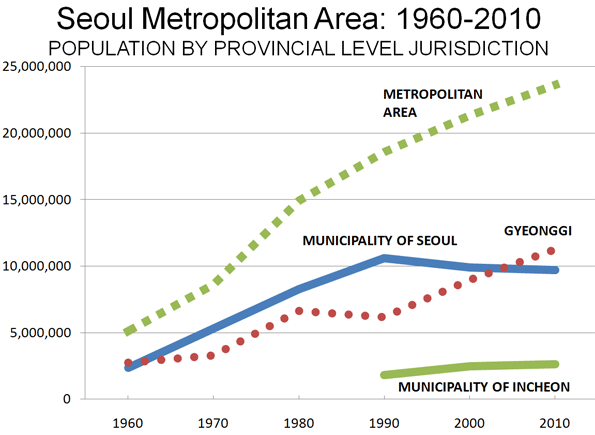

Based upon the preliminary results of the South Korea 2010 census, Seoul has become the world’s third largest metropolitan area. The jurisdictions making out the metropolitan area, the provincial level municipality of Seoul (which is the national capital), the province of Gyeonggi and the provincial level municipality of Incheon now have a population of approximately 23.6 million people. This is third only to Tokyo – Yokohama, which has a population of approximately 40 million and Jabotabek (Jakarta), which is approaching 30 million. While international metropolitan area population estimates should be taken with a "grain of salt," (Note 1: Metropolitan Areas) the rise of Seoul is nearly unprecedented in the high-income world. Further, many more people are projected to move to the Seoul metropolitan area as the trend of rural and smaller area migration to larger urban areas continues.

A Difficult History: However, any analysis of Seoul and its progress must begin in the context of the overall economic progress of South Korea and its difficult history.

Seoul was a major battleground in the Korean War of 1950 to 1953. During 1950 alone, military control of the municipality of Seoul changed hands four times. Today, despite the precariousness of the political situation on the Korean Peninsula, the northern suburbs of Seoul are as close as four miles (seven kilometers) from the demilitarized zone, which forms the border with North Korea.

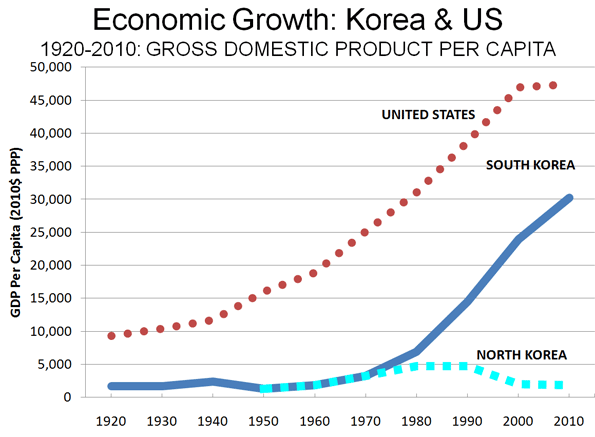

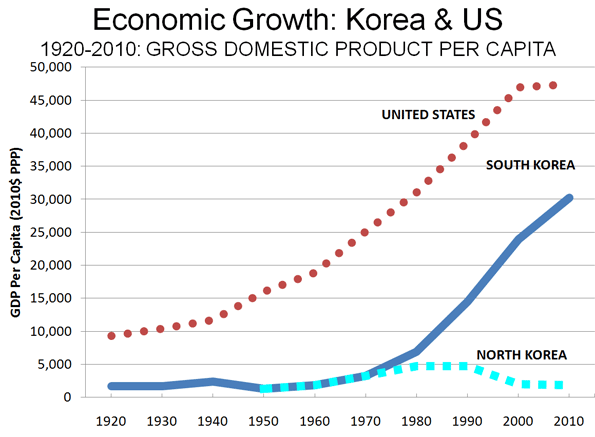

Strong Economic Growth: A very poor country even before the war, South Korea has been an economic success story. Based upon data produced for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development by the late economist Angus Maddison, South Korea had a gross domestic product per capita (purchasing power parity) of less than $1300 (2010$) in 1950. It had peaked, as a Japanese colony, somewhat above that level before World War II, but never approached one quarter of the GDP per capita of the United States and averaged less than one third of then high income Argentina.

After the Korean War, initial economic progress was slow. As late as 1965, South Korea’s GDP per capita was less than that of Mozambique. Since that time, South Korea’s GDP per capita has risen from approximately $2000 to $30,200 in 2010 It exceeded Argentina in the 1980s.

South Korea today has a higher GDP per capita than Spain and New Zealand and less than 10 percent behind the European Union, on which it is gaining quickly. As the capital, the Seoul is a prosperous metropolitan area in a prosperous country.

South Korea’s prosperity is also considerable contrast to that of North Korea’s. South Korea’s GDP per capita is more than 15 times that of North Korea (Figure 1). This would make any future reunification far more expensive for South Korea then Germany’s unification was for West Germany, because the economic disparity, though substantial, was much less.

The Urban Area: Growing and Dense: The Seoul urban area (area of continuous development) includes the municipality of Seoul and also includes the urbanization of Incheon, to the west and substantial suburban development in the province of Gyeonggi on the other three sides (Note 2: Urban Areas). Based upon an analysis of data from the 2010 census, we have estimated the Seoul urban area population at 22.5 million. The next edition of Demographia World Urban Areas: Population & Projections (current edition) will show Seoul to be the world’s third largest urban area, trailing only Tokyo-Yokohama and Delhi (which recently passed Mumbai to become India’s largest urban area). Jakarta, the second largest metropolitan area, ranks as the fourth largest urban area, though will soon pass Seoul, because of much stronger growth. Among high income world urban areas, Seoul’s population growth has been greater than that of any other since 1950 except for Tokyo-Yokohama. Seoul added more than 20 million people, while Tokyo-Yokohama added more than 25 million people. By comparison, New York added less than 10 million people and Paris added 4 million people.

Seoul’s population density is among the highest of the world’s affluent urban areas. With population density of 27,000 people per square mile (10,400 per square kilometer), Seoul ranks second in the high income world among urban areas of more than 5 million people, trailing only Hong Kong, which is more than twice as dense. Thus, Seoul is more than twice as dense as Tokyo-Yokohama, three times as dense as Paris and four times as dense as Los Angeles or Toronto, the densest urban regions in North America.

With the exception of Hong Kong, no first world urban area has the density of high rise condominium developments as are found in Seoul. While virtually all of the recent urban expansion in both population and geography has been in the suburbs, nearly all of the new residences are in high rise buildings.

Seoul is also the home to massive city real estate developments. For example, Ilsan, in Gyeonggi is a very large planned high-rise community to the north of the Han River (which bisects the urban area), west of Seoul and north of Icheon. Most of Ilsan was developed by the early 2000s. The high rise development of Songdo, four miles (seven kilometers) south of the core of Incheon is intended to be home to 75,000 people and 50 million square feet of office space.

Seoul’s Han River is crossed by multiple bridges, including architectural icons. A new international airport (Seoul-Incheon) was opened in 2005, 43 miles (70 kilometers) away from the Seoul central business district. This airport, on an island west of Incheon is most remote international Airport among the world’s megacities (urban areas over 10 million population), 8 miles further even than Narita International Airport from central Tokyo. Domestic flights continue to operate out of Gimpo Airport, which is halfway between the cores of Seoul and Incheon.

Distribution of Population Growth: The municipality of Seoul – the capital district – is one of the largest municipalities in the world, with nearly 10 million people (Note 3: Municipalities). However, like many core municipalities that have not expanded their boundaries, Seoul is losing population. The 2000 census shows the population to have declined 900,000, or nearly 10 percent, from 1990. The population loss during the 2000s was a somewhat more modest 200,000.

Since 1990, all the population growth in the Seoul metropolitan area since has been in the suburbs. The province of Gyeonggi has gained more than 5 million residents, while the municipality of Incheon has added more than 800,000 residents. During the 2000s, the province of Gyeonggi added enough population to exceed the municipality of Seoul as the largest provincial level jurisdiction in the metropolitan area (Table).

| Seoul Metropolitan Area Population: 1960-2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Year |

Metropolitan Area |

Provincial Level Jurisdiction |

| Seoul |

Gyeonggi |

Incheon |

| 1960 |

5.1 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

|

| 1970 |

8.6 |

5.3 |

3.3 |

|

| 1980 |

14.9 |

8.3 |

6.6 |

|

| 1990 |

18.6 |

10.6 |

6.2 |

1.8 |

| 2000 |

21.4 |

9.9 |

9.0 |

2.5 |

| 2010 |

23.6 |

9.7 |

11.3 |

2.6 |

| In Millions |

|

|

|

|

| Incheon created from Gyeonggi in 1981 |

|

|

The Future? There is also some question about whether Seoul will remain the national capital. In 2004, the national government decided to move the capital to Gongju, 90 miles (150 kilometers) south of Seoul. The decision was both preceded and followed by considerable political jockeying and it appears that the government is backtracking on the capital move (though construction has begun).

Regardless of the eventual fate of the new capital, Statistics Korea projections indicated that the Seoul metropolitan area will continue to expand. The population of the municipality of Seoul is expected to decline through 2030 while the suburban jurisdictions of Incheon and Gyeonggi are expected to continue their growth. Further, more rapid growth is anticipated in North Chungcheon and South Chungcheon provinces as the metropolitan area, and perhaps even the urban area spreads further to the south. This larger metropolitan area is projected to grow to more than 31 million people by 2030.

—-

Note 1: Metropolitan Areas: Metropolitan areas are the economic dimension of the urban form. They represent the labor markets (area from which people commute to the urban area) and thus include both the urban area and surrounding economically attached rural and exurban areas. There are no international standards for delineating metropolitan areas and most national statistical agencies have no such delineation. The nations that do giving me metropolitan areas have differing standards and even within nations there are substantial difficulties. The only serious attempt to define metropolitan areas based upon consistent standards was by urban expert Richard L. Forstall (who ran the Rand McNally "Ranally" international metropolitan area program), Richard P. Green and James B. Pick. The complexity of the research is indicated by the fact that their list is limited to the top 15 in the world. Other attempts to delineate metropolitan areas generally rely on complete second or third level jurisdictional boundaries, such as counties, states or provinces. This can lead to specious comparisons of densities, because the jurisdictions that are used vary so much in size. This is perhaps best illustrated by comparing Portland and Riverside – San Bernardino. In 2000 (latest available data), the Riverside – San Bernardino urban area had a densities slightly higher than that of Portland. Yet the metropolitan areas vary greatly in size, due simply to the size of the counties that comprise them. The two counties of the Riverside – San Bernardino metropolitan area cover four times as much land area as the seven county Portland metropolitan area.

Note 2: Urban Areas: urban areas are the structural dimension of the urban form (the "urban footprint"). Urban areas are the area of continuous urban development. They may also be called urbanized areas (such as United States, United Kingdom, France, India and Canada); urban centers (Australia) or urban agglomerations (United Nations). Canada will switch its terminology for urban areas to "population centres" in the 2011 census. The distinction between urban areas and metropolitan areas can be confusing and has led some internet – based lists to somewhat indiscriminately mix the two. Moreover, the term "urban area" has even been used to denote an area well beyond the continuous urbanization (more akin to a metropolitan area), such as in its definition by statistics New Zealand.

Note 3: Municipalities: international comparisons of municipalities (often called "cities," which is a term that can also be used for two substantially different concepts, metropolitan areas and urban areas) are generally invalid, because there is no geographic or population criteria between or even within nations by which municipalities are defined. This is illustrated by the fact that the world’s largest municipality, Chongqing is largely rural, not urban, and covers an area approximately the size of Austria or Indiana. While the municipality of Chongqing (and virtually all other Chinese "cities") is larger than its metropolitan area, municipalities may be far smaller than their metropolitan areas. For example, the municipality of Melbourne ("city of Melbourne") has less than 2 percent of the metropolitan area population, while the municipality of Atlanta has less than 10 percent of the metropolitan area.

Note 4: The United Nations population estimates show the Seoul urban area to be limited to the municipality of Seoul which produces a far smaller estimate of less than 10 million people.

—–

Photo: Suburban Seoul (by author)

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life ”

”