The New Zealand Government recently decided to follow the example of Montreal and Toronto by amalgamating the six City councils and the single Regional Council of the Auckland Region to create a united “Super City” of 1.4 million people.

Like similar amalgamated bodies, the new Auckland Council, which came into being on the 1st November, 2010, has fallen for the notion of regionally determined smart growth built around a huge investment in heavy rail.

Backed by a Regional Council totally committed to Smart Growth, every decision was driven by the need to “get people out of their cars” rather than to improve mobility. Since the 1990s they have fought for densification as a means of enabling more public transport. The bus lanes linking the north shore to the CBD are for buses only. HOVs are not allowed on and nor are shuttle buses. The planners openly argue that the near empty lane is to encourage people to get out of their cars on the congested motor way lanes and take the bus. Also they are inserting bus only lanes into our already narrow urban streets. Cars are just being crowded off the streets.

Consequently, congestion has grown progressively worse, but this was seen as only further evidence of the need to invest in rail.

Many of us thought that the election which replaced the Labour Government with a coalition of National and Act, two conservative-leaning m parties of the Right, would put an end to this “trip backwards to the future”.

But, as has happened elsewhere, the Right adopted the policy while the Chambers of Commerce and similar groups championed the mega-amalgamation on the grounds of efficiency. They saw huge savings to be made in having only one Mayor and one council, and one plan, and one rate, and indeed, ideally only “one of everything”.

Yet instead of searching for a new, modern way to develop this region, Len Brown, the left of center first Mayor of the Auckland Council has backed a “Vision for Auckland” built around an extensive rail network – including a rail link to the Airport, a CBD rail loop, light rail on the surface streets, and a rail tunnel under the Waitemata harbour.

Residents of surrounding areas may not share this Vision – especially if they have to share the costs. This is the kind of division that led to Montreal’s recent de-amalgamation.

The Mayor supports his Vision with claims that professional analysis and expert advice will show that these projects are viable and necessary and that Government must fund them.

One has to wonder where he gets his advice from.

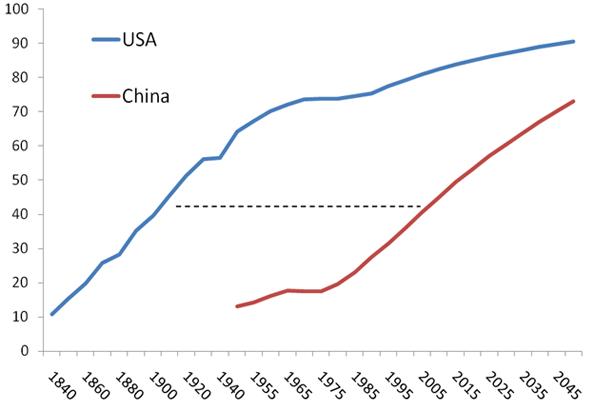

No investment in rail in New World cities since the 1980s has resulted in a reduction in congestion. In most cases congestion has increased and public transport market share has diminished because the investment into rail has diminished funds for roads, buses and High Occupancy Toll lanes, measures that actually work to increase mobility

The Government should also be aware that the international engineering firms at come in behind these proposals for rail investment (and similar major project works) have a proven expertise in getting a foot in the door with low bids then cranking up the costs afterwards. These projects routinely come in over budget.

Furthermore, some research reveals that Heavy Rail (as is proposed for the Auckland network) has a worse record for cost overuns than Light Rail projects. Early projects have a worse record than more recent projects, possibly because the tendering firms have gained experience over time in how to fool the public, and the population with low ball estimates of cost and exaggerated estimates of ridership.

“Megaprojects and Risks: and anatomy of ambition.” (Click on the link to read the Public Purpose review.)

This has become a clearer pattern, as seen in projects as diverse as the English Channel Tunnel, the Great Belt rail-road bridge between Zealand and the Jutland Peninsula, and the Oresund road-rail bridge between Copenhagen and Malmo, Sweden.

So this is not just an American problem.

The “Chunnel” trains, for example, were projected to carry 15.9 million passengers in the first year of operation (1995) but by the sixth year (2001) ridership was 57% lower at 6.9 million. The cost overrun was 79%.

The Flyvbjerg data set of international studies, including rail and road schemes, contained 258 projects.

- 90% had significant overrun of costs.

- Rail projects had the highest cost escalation (45% over)

- Road projects had the lowest escalation (20% over)

- The average ridership was 61% of forecast and the average cost overrun was 28%.

The figures for rail alone were worse.

An even more pessimistic summary of performance is contained in a power-point presentation by Lewis Workman of the Asia Development Bank, Predicted vs. Actual costs and Ridership – Urban Transport Projects, May 2010.

This presentation notes that the problem is actually worse in developing countries. The Bangkok metro “actual ridership” fell short of the projections by 55%. The authors ask the question “Lies or Incompetence?” and their answer is “Probably Both.”

New Zealand’s Minister of Transport, Stephen Joyce is well prepared to shout louder than the “one voice” of the new Auckland Council. In September 2009 he warned that the Government is committed to spending NZ$500m on the city’s rail electrification projects – but funding cost over-runs is not an option.

His officials have identified up to $200m of potential cost over-runs in the NZ$1.6bn project, which is still on the drawing board.

One of the first rail upgrade contracts demonstrates his concerns are justified.

The Manukau Rail Link was initially estimated to cost NZ$40 million [2006] which subsequently rose to NZ$72 million [2008] and the latest figure is NZ$98 million. This is for a 1.8k link and station southwest of Manukau CBD.

The Minister should hold fast to this position. But maybe he should also hold fast to the position that Auckland Council will not be compensated for any revenue shortfalls on account of lower than projected ridership.

Maybe the Auckland Council would then take on board the remedies for these “foot in the door” feasibility studies, or get those who make the studies to stand behind them with some form of guarantees backed up by insurance.

The recent experience with BART suggests that US politicians should learn to play equal hard-ball.

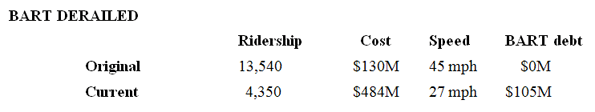

Similarly the 5 km BART connection to the Oakland Airport (on the East Bay) was originally projected to cost $130 million and cater to more than 13,000 passengers daily. However, after a decade of delays, those forecasts have been changed to $484 million – a cost increase of say 250%, and 4,350 passengers a day – a ridership shortfall of say 60%.

The crystal balls are not getting any clearer.

Consequently, according to a study by transport planners Kittelson and Associates, each new passenger who uses the system during its estimated 35-year lifespan will be supported by a subsidy of $102 – on top of the fares they pay. This is more than 10 times the original projected subsidy of $9 per new passenger. This combination of cost overrun and ridership shortfall has had a catastrophic effect on the viability of such projects.

But the boosters are not deterred. They say it should be built because “the community wants it”, which sounds familiar.

The table below shows this the Oakland Airport rail link is clearly a project that should never be started. Even the “rapid transit” speed will not be delivered.

Politicians’ Visions reward the citizens with nightmares.

These large multi-national engineering consulting firms have become accustomed to treating Governments – both Central and Local – as giant ATM machines.

It’s time to take away their plastic.

Owen McShane is Director of the Centre for Resource Management Studies, New Zealand.

Photo by bcran