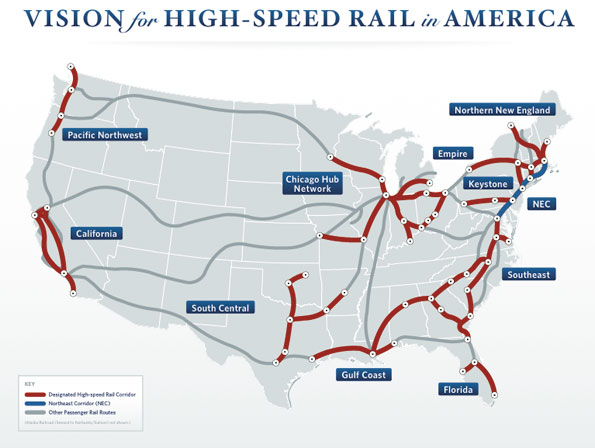

Given that Warren Buffett ponied up $44 billion in cash and stock to take private the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad, I wonder why President Obama is betting that the way to lift the country out of stagnant growth is to invest another $50 billion, in public funds, to swing aboard the dream of high-speed intercity rail.

According to the administration, new money needs to be allocated to such high-speed rail (HSR) projects as those between San Diego and Sacramento, Orlando and Tampa, and — my personal boondoggle favorite — the DesertXpress between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, a $4 billion bet that getting high-rollers to the blackjack tables will lift the U.S. economy out of its doldrums.

To establish some track cred, I spend much of my life dreaming about trains, consulting timetables on how to catch them, and plotting trips that might end up on night trains to Butterworth (the station for Penang) or Iasi (change in Ungheni, on the Moldovan border).

More to the point, I have ridden nearly all the high-speed trains — in China, Japan, and France — that are being held as speeding examples of what the United States could build if Congress would fork over another $50 billion, and if the President could appoint a railroad czar with the acumen of E. H. Harriman.

Painful as it is for me to admit, the $50 billion high-speed stimulus package is a way to lay track to nowhere.

Take the rail link between Tampa and Orlando that imagineers hope will shuttle theme-parkers at speeds reaching 186 m.p.h. President Obama has already thrown $1.25 billion at the line. Presumably, the named expresses will be The Absentee Balloter and The Recount.

Local officials have been busy buying rights-of-way and planning stations in their home districts, although, oddly, downtown Orlando is given a miss.

When the stimulating project is finished for close to $3 billion, a family visiting Disney World can drive to the station, catch a high-speed train to Lakeland, pay a cab driver to take them to the Detroit Tigers spring training facility, and watch a game. After the game, to get back to their hotel, they would do the trip in reverse. Or they could drive to Lakeland in the hour projected on MapQuest. What would you do?

The reason high-speed rail has more allure in Europe is because people live in cities. Nor do they like driving their cars on the cobblestones of historic quarters. In China, cities are megalopolises and few Chinese own cars or want to drive them across the vast country. France is a one-city country, so all rail lines lead quickly to Paris, as Louis XIV would have wanted.

In Target-specked America, everyone has a car, lives out-of-town (“we like it here”), and, except for a few New Yorkers, drives everywhere, except when they fly. Orlando might be the most car-centric suburban cluster in the country.

Not long ago, I had to drive from my Orlando motel just to find dinner. Is it remotely possible that Floridians will hop a high-speed train to rush them into downtown Tampa, which after 6:00 PM, when I was last there, looked like Death Valley?

I can imagine Chicagoans taking a fast train to St. Louis, as opposed to flying out of O’Hare. But normal trains, and lots more of them, that reached the 100 M.P.H. speeds of the 1930s would suffice in most corridors.

What logic explains betting public billions on a concept — intercity rail transportation — that the same government has devoted countless resources to destroying? Through most of the twentieth century, the American government used public money to lay down roads and interstates, and to subsidize airports, that choked off demand for passenger rail service.

Federal bodies like the Interstate Commerce Commission, which regulated the profits out of the industry, killed off the national jewel that was the railroad network in the 1920s, with its 250,000 miles of track.

It is doubtful whether the combined forces of the Texas Railroad Commission, Jay Gould, railroad baron Daniel Drew, and Leland Stanford, could have kept passenger service alive when confronted by a government that lived by the rail credo of William Vanderbilt, who said: “The public be damned.”

Between the 1970 collapse of the Penn-Central and the 1980 passage of the Staggers Act — President Carter’s successful deregulation of the industry — most Class I railroads flirted with bankruptcy, earning less than one percent on their capital, and were unable to set rates competitively.

The Staggers Act got the government off the rails; since then, the vital signs of the business have flourished to the point of attracting Warren Buffett’s capital. Trackage has been rationalized from 270,623 to 160,734 miles. Container traffic has grown from three to twelve million. Productivity has more than doubled, and, adjusted for inflation, prices are down (although the big coal companies hate deregulation, and they are forty-five percent of the business).

I mourn the loss of such evocative railroad names as Grand Trunk, Boston & Maine, Nickel Plate, and Chicago & Alton (for which my grandfather worked). Nonetheless, from more than thirty failing companies, mergers have produced five thriving Class I railroads. The industry employs 164,439 works at an average annual wage of $72,836. Even the government made a profit by spinning off Conrail.

Despite such a success story, renewed federal intervention threatens the freight revival. A Bushism called Positive Train Control, a computer system to reduce accidents and allow tighter spacing between trains, will cost the industry $15 billion, although there’s little proof that it will work better than what Casey Jones would have known as the “dead man’s hand” (a grip that stops the train if the engineer dies).

The new stimulus package represents the government belief that it understands the passenger business better than either the industry or the capital markets, neither of which wants in on any high-speed rail action. (You would think the Vegas Highball would tempt Wall Street.)

More to the point, the government’s record with Amtrak ought to disqualify it from any say in how to run a railroad.

Freight companies are leery of high-speed rail because of what it might do to their rights-of-way. Many plans project HSR running on freight lines, which are notorious for “putting the varnish in the hole.” Meaning: let the passengers wait on a siding while a freight train goes through.

I love trains, so I take Amtrak often and everywhere, and it’s an endless disappointment, with late trains, cold food, clogged toilets, and indifferent “customer service representatives.” Even though I collect its schedules and prowl its web site, Amtrak reminds me of Aeroflot.

Nor is Amtrak’s meandering route system anything more than the arteries of a patronage network that would warm the heart of E.H. Harriman, who knew all about railroad patronage. Remember Mark Twain’s aside: “I think I can say, and say with pride, that we have some legislatures that bring higher prices than any in the world.”

Before the United States rushes further into high-speed rail, it needs first to decide whether passenger rail service should be a public or private business. A white paper is due out this fall, but I am not holding my breath.

Personally, I like the English model, flawed as it may be, in which BritRail (the U.K. Amtrak, but with cold pork pies) was privatized, and routes around the country were sold to private railways. A government corporation, albeit one starved for capital, held on to the track and infrastructure.

On the surface, anyway, British trains are now shiny, clean, faster, and a pleasure to ride. The airline Virgin has some trains, and newer lines, like Eurostar, have come into business. It used to take BritRail ninety minutes to chug out to Cambridge from central London. Now two companies compete on the line, and the trip is forty-five minutes.

I doubt that Warren Buffett wants to get the Burlington Northern back into the passenger business. His bet is that he can monopolize container traffic from Asia to Chicago and maybe, someday, with another deal, to New York.

With proper incentives, why wouldn’t a private company bid for the line between Boston and Washington, or San Diego to Los Angeles? Or maybe Disney could integrate the Orlando-Tampa train into its monorail? At least it could fill the seats without stimulus money.

Matthew Stevenson is the author of Remembering the Twentieth Century Limited, winner of Foreword’s bronze award for best travel essays at this year’s BEA. He lives in Switzerland (near the station).

Photo: Amtrak (although this particular one is the Pacific Surfliner in Del Mar, California)

Map: The White House