China’s ascension to the world’s second-largest economy, surpassing Japan, has led to predictions that it will inevitably snatch the No. 1 spot from the United States. Nomura Securities envisions China surpassing the U.S.’ total GDP in little more than a decade. And economist Robert Fogel predicts that by 2050 China’s economy will account for 40% of the world’s GDP, with the U.S.’ share shrinking to a measly 14%.

Americans indeed should worry about the prospect of slipping status, but the idée fixe about China’s inevitable hegemony–like Japan’s two decades ago–could prove greatly exaggerated. Countries generally do not experience hyper-growth–the starting point for many predictions–for long. Eventually costs rise, internal pressures grow and natural limitations brake and can even throw the economy into reverse.

Instead the U.S. has a decent chance of remaining the world’s pre-eminent economy not only over the next decade or two and even by mid-century. There are five key reasons for this contrarian conclusion.

1. If Water is the “new oil,” China faces a thirsty future. China’s freshwater reserves are about one-fifth per capita those of the United States, notes Steve Solomon, author of Water: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power and Civilization. Much of that supply has become dangerously polluted; ours , for the most part, has become cleaner.

More important, the U.S. has become more efficient in its water usage, says Solomon. China, with a far less developed economy, will face increasing demands from industrial and agricultural users as well as hundreds of millions of households that now don’t enjoy easy access to clean drinking water.

2. China’s energy demands are soaring, but it lacks adequate domestic resources. China impresses journalists and policy-makers with grand “green” projects and heavy investment in renewables, but two-thirds of the country’s energy comes from that dirtiest of sources. China burns more coal than the U.S., Europe and Japan combined, often using very primitive technology. It has now overtaken the U.S. for the dubious honor of the most total energy use and highest greenhouse gas emissions. Since 1995 China’s dependence on foreign oil has grown from near to approaching 60%, and the country, long a coal exporter, is becoming a major importer of that unfashionable fuel.

The U.S. meanwhile sits on largely untapped fossil fuel resources, including coal, natural gas and oil. Add Canada to the equation and North America ranks second, behind the Middle East, in energy resources. In contrast to China, America’s energy use and greenhouse emissions appear to be dropping while still enjoying enormous, still largely untapped renewable resources, particularly from wind power in the Plains and biomass.

3. Food remains pressing problem for China. Scarce water, mass pollution and high energy costs all will limit China’s future food production. By some estimates acid rain falls on a third of all agricultural land; some climate experts predict long-term reductions in the country’s vital rice crop.

Plagued by floods, China now will have to look to U.S. and Canada to meet demand for crucial foodstuffs, particularly corn. And the food deficit may get worse over time: As China becomes wealthier, demand for high-protein foods like beef and pork will increase. The U.S. remains the world’s most reliable supplier of many of those agricultural products.

4. China’s rapidly aging population and shrinking workforce will slow growth, perhaps dramatically, by the next decade. Like that of the “Asian tigers” in the ’70s and ’80s, China’s rapid growth has been propelled in part by an expanding young workforce. Due to a very low birthrate, however, this trend will reverse within a decade or two. By 2050 31% of China’s population will be older than 60, compared with barely one-quarter in the U.S. There will be over 400 million elderly, with virtually no social security and few children to support them. Also worrisome: The preference for male children has skewed sex demographics dramatically, with roughly 30 million more marriageable boys than girls.

The logical solution to this dilemma would be immigration, but China’s culture appears far too insular for such an event. Rather than a benevolent “socialist” super power China, whose population is made up over 90% Han Chinese, will bestride the world as a racially homogeneous, and communalistic “Middle Kingdom.” In contrast, the U.S., despite occasional fits of nativism, remains remarkably successful at integrating cultures from around the globe.

5. Dictatorship thrives sometimes in a “take off” period, but often fails to compete well with more open societies during later stages of growth. Many American intellectuals and journalists celebrate China’s achievements, much as some of their predecessors admired past “successful” economic regimes in fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and the late Soviet Union. The longest lasting of the authoritarian superpowers, the Soviet state massively misallocated its resources in its unsuccessful competition with the more flexible systems of the U.S. and its allies.

Big Brother economies experience more subtle problems. Chinese entrepreneurs , according to a survey by the Legatum Institute in London, depend far more than their more nimble and self-reliant Indian counterparts. Overweening Chinese state power also might be chasing many foreign businesses–and some developing countries– toward more congenial investment and trade partners.

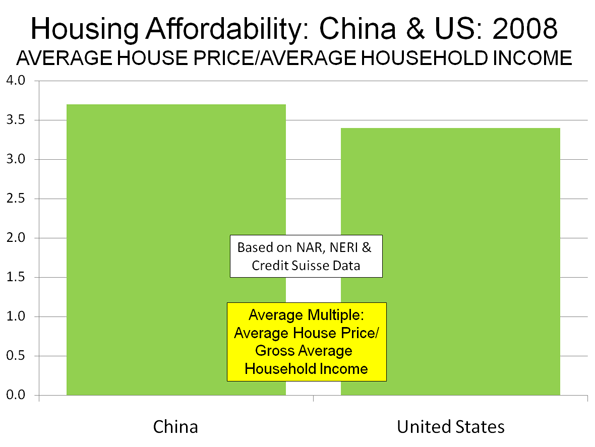

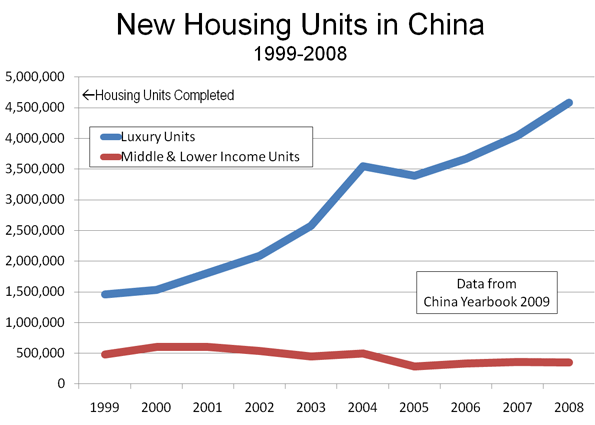

For all these problems, the Chinese emergence remains the dominant business event of our epoch. But world-wide dominion seems highly unlikely. One often overlooked factor: political problems stemming from growing inequality in this officially Marxist state. Over the past 20 years China’s income distribution pattern has shifted from the relative egalitarianism of Sweden, Japan or Germany to that of countries like Argentina and Mexico.

The class divisions will deepen further as growth inevitably slows. Roughly one-third of 2008’s 5.6 million university graduates have been unable to find work. Things are even worse for those less skilled, rural residents and small manufacturers.

Ironically, the Communist Party appears to further concentrate wealth and power; most of the richest people in China are linked to the party. Policies push growth, but with diminishing rewards to the masses. Over the last decade the share of GDP going to consumption dropped from 46% to less than 36%.

Of course, a comparatively small number of skilled, with often well-connected professionals and investors flourishing, but opportunities for economic advancement may now be scarcer for most workers compared to the earlier period of China’s remarkable “liftoff” after 1980. Conditions for the working class in China remain more akin to Dickensian England than a Marxian “worker’s paradise.” China’s dismal health care system for example, ranks according to the World Health Organization, among the world’s most inequitable, 188th out of 191 nations.

Not surprisingly, class anger has reached alarming proportions, with almost 96% of respondents, according to one recent survey, agreeing that they “resent the rich.”

America also faces its own share of social problems but not to such an extreme degree. Many Americans resent the affluent, but also dream of becoming them. How else to explain the popularity of paeans to bourgeois vulgarity like Housewives of New Jersey?

In the coming decades China, not the currently depressed U.S., may face greater headwinds. America’s biggest enemy will prove to be not China, but itself. The U.S. needs to move toward a pro-growth course driven by investments in our productive economy, basic infrastructure and skills-based education as well as sustainable immigration and population growth levels. If the country does these things then Americans will someday look back at their current Sinophobia as a delusion dressed up as irresistible conventional wisdom.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.

Photo: Steve Webel