In a time when many European nations are burdened by high debts and difficulties to get spending under control, the Swedish economy is amongst the most well managed in Western Europe.

The nation’s GDP fell dramatically, by more than four percent, when the financial crisis struck. This decline was twice the average of the OECD-15 countries. Despite this, Swedish employment actually increased between the last quarter of 2006 and 2009.

Sweden was hit hard by the crisis since the country relies heavily on exports. On the other hand, the new center-right government that was elected in 2006 has implemented considerable supply side reforms in terms of tax cuts and tightening of welfare and social insurance benefits. These reforms have encouraged work rather than dependence on handouts, balancing out much of the negative impacts of the crisis.

This reformist trend is rarely acknowledged in the United States. However, during the last two decades both center-right and social democratic governments have implemented free market reforms, tax reforms, pension reforms, privatization of state owned firms and increased reliance on private production of public services such as education and health care.

The country has also followed a surprisingly conservative fiscal policy. The welfare state remains, but Sweden is no longer an extreme case in terms of socialist policies. This now helps Sweden stay on top as Europe starts on the road to recovery.

Bu what are Sweden’s long-term prospects for turning the crisis into an opportunity for growth? As history shows, when the macroeconomic shocks subside, growth to a large extent depends on innovation and entrepreneurship. Typically, entrepreneurship is not included as a factor in economic models. In real life however, the business climate matters.

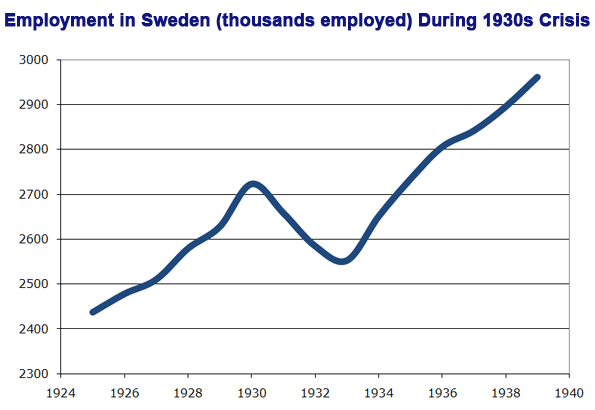

This is illustrated by how well Sweden handled the great depression. Between 1930-33 170,000 jobs were lost, leading to a six percent drop in employment. However, the downturn soon turned to growth.

At this time, Sweden was far from a socialist welfare state. The nation boasted low taxes, a flexible labor market and a good business climate. The solution for many who lost their jobs was to start their own business.

Job creation spurred. Already in 1935 more people were employed compared to before the depression. One reason is that the Swedish economy already had gone through a recession in the 1920s, sparking structural changes.

New and innovative ventures were started to replace the jobs that had been lost. Several famous Swedish firms, that still today remain as top employers, were formed during and shortly after the depression, such as: Volvo Aero, the mining company Boliden, Securitas and SAAB.

Swedish social democrats have a surprisingly strong tradition of being quite pro-growth, and even pro-business. However, the hard left resurgence in the 1960s, culminating in the turmoil of 1968 radicalized the Social Democratic party. The tax level started climbing (through hidden taxes on labor and consumption), the labor market became dominated by labor union influence and regulations and the incentives for work, education and entrepreneurship were severely limited.

As policy shifted, the growth of highly successful entrepreneurial ventures stagnated. A study by economist Sten Axelsson (Axelsson 2006) has examined the entrepreneurial ventures that had the highest revenues in Sweden in 2004. Only two out of 38 firms had been formed after 1970. If the firms were instead ranked after how many the employed, not a single one was shown to have been formed after 1970!

Another study by economist Jonny Ullström (Ullström 2002) has looked at all the firms that were started in Sweden between 1986 and 1996. Among the 180,000 examined firms, 90 percent had fewer than five employees in 1997. Less than one among a thousand firms had 50 employees or more. Only eight of all the firms had 200 employees or more.

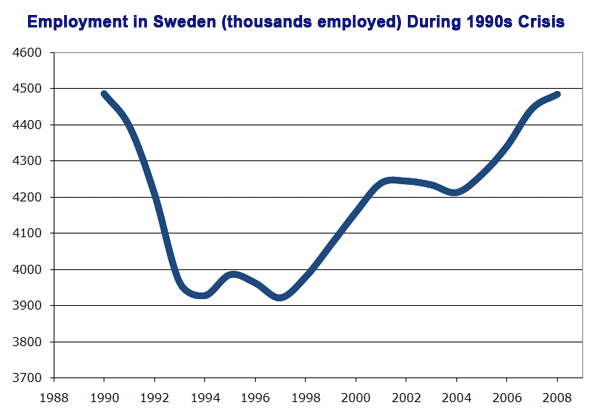

The drop in entrepreneurship affected Sweden’s ability to deal with downturns. In the beginning of the 1990s, a new crisis hit Sweden. The global economy was growing strongly, but major obstacles faced the Swedish welfare state. Employment fell with almost twelve percent between 1990 and 1993. Within a few years the economy began to grow again. But employment stagnated. It remained until 2008 until Sweden reached the same level of employment as before the crisis.

However, due to the previously mentioned reforms, the Swedish economy in 2008 was far more flexible than previous years, and thus better able to withstand the international downturn. Since the beginning of the 1990s, Swedish politicians amongst both the right and the left have realized the importance of moving towards greater share of economic freedom and following a generally fiscally conservative path In this time of worldwide crisis, this has helped Sweden’s economy to perform better than many others.

This is not to say that more reforms are not needed to promote growth and entrepreneurship. Labor market regulations and taxes still depress successful entrepreneurship. For example, a person increasing her or his income with 100 Swedish Kronors has to pay fully 74 Kronors in hidden and visible taxes on employment and consumption taxes.

Successful entrepreneurs are often highly educated people who already have a good career within large firms. But why spend time and energy on a new venture if up to three quarters of the gains are taxed away?

Sweden is a nation with a strong history of entrepreneurship, great scientific institutions and strong working ethics. Today the nation stands stronger thanks to reforms towards greater level of economic freedom. But as long as taxes and labor market regulations block the way of growing businesses, the country cannot hope to repeat its stellar recovery course seen during the 1930s.

Nima Sanandaji is president of the Swedish think tank Captus. He is the author of the book ”Entrepreneurs who go against the stream – what the 90s successful entrepreneurs can teach us” (Swedish title: ¨”Entreprenörer som går mot strömmen – vad 90-talets succéföretagare kan lära om dagens utmaningar”) for Fores.

Photo by: jdlasica

References:

Axelsson, Sten (2006). ”Entreprenören från sekelskifte till sekelskifte – kan företag växa i Sverige?”, in Dan Johansson och Nils Karlsson (ed.), ”Svensk utvecklingskraft”, Ratio.

Ullström, Jonny (2002). ”Det svenska nyföretagandet 1986-1997: förändringar i företagsstruktur och sysselsättningseffekter”,Vinnova.

“High Rise or House with Yard” stands alone in claiming that New York City is less costly than its suburbs. The most recent (and authoritative) ACCRA cost of living index for Brooklyn is a

“High Rise or House with Yard” stands alone in claiming that New York City is less costly than its suburbs. The most recent (and authoritative) ACCRA cost of living index for Brooklyn is a