This is an excerpt from “Enterprising States: Creating Jobs, Economic Development, and Prosperity in Challenging Times” authored by Praxis Strategy Group and Joel Kotkin. The entire report is available at the National Chamber Foundation website, including highlights of top performing states and profiles of each state’s economic development efforts.

States throughout American history have done everything they can to cultivate, attract, retain, and grow the businesses that comprise the most fundamental building blocks of their economy. Even in today’s volatile global economy states with severe unemployment and budget woes can point to policies, programs, and investments that foster new economic opportunities and create jobs.

Read the full report.

Read part one in this series: The Jobs Imperative: Power to the States

Many state economic development organizations were originally established with business recruitment and attraction as their primary focus. But today’s mix of state approaches to economic development has moved well beyond earlier, sometimes singularly focused attempts to lure footloose businesses with huge financial incentives and/or by offering a business climate based on cheap labor, low taxes, and lenient regulations.

States, nonetheless, still compete with each other for companies in “traded sectors” and jobs in the global economy, either directly or by virtue of unique assets and resources, and this sometimes involves financial incentives and tax abatements. But there is growing momentum among governors and state legislatures to grow their economies from within by creating a new set of competitive advantages that include building human capital through workforce development and training, harnessing the power of science and technology assets, making strategic investments in infrastructure, reaching out to global markets, developing opportunities related to energy and the environment, and spurring entrepreneurship and innovation.

Generally, state economic development efforts include an interrelated array of policies, programs and investments, falling into three major categories: (1) an entrepreneurial approach focusing on new business and technology-based development, oftentimes with a focus on bolstering productivity and innovation; (2) recruitment, expansion, and retention strategies emphasizing financial incentives or investments and other programs, including international trade and export promotion; and (3) “fertile soil” policies28 that create the conditions for growth that will benefit almost any type of business by streamlining governmental regulation, optimizing taxes, investing in infrastructure, and/or by providing a better-educated, more highly skilled work force.

While it is up to state governors and legislators to set the environment for development to flourish, ultimately economic development success is defined by execution at the local and regional level. With well designed state-implemented development tools, effective workforce development and skills training systems, and strong infrastructure, states can give local economic developers the power to assist the growing businesses, to broker the key partnerships, and to lead the key initiatives that create the jobs needed to sustain our growing population.

Most of all, states must carefully weigh policy to refrain from constructing barriers to private enterprise growth. Many of the most effective economic development initiatives start from grassroots efforts or private sector business leaders, so supporting these efforts from the state level is imperative.

Measuring the States: A List of the Top Performers

A primary goal of any state economic development program is not only to increase the number of jobs in the state, but to improve the quality of jobs and the overall prosperity of the state’s residents.

This study combines metrics for each economic development policy area to measure overall high performers in each policy topic area. States are compared in each metric and top states are determined by a composite comparison of all metrics in overall performance and in each policy area. For a full description of all metrics and results for each state as well as top performers in exports, innovation, workforce development, infrastructure, and tax and regulation, see the full report.

To establish the overall best performers we combined measures of Job growth rate since 2000 and since 2007; Gross State Product (GSP) measures: real GSP growth since 2000, GSP per job 2008, Growth in GSP per job 2000-2008; and income: per capita personal income growth 2000-2009 and median four person family income adjusted for cost of living, 2009.

Top Overall Growth Performers

- North Dakota – While North Dakota’s low unemployment and recession resistance is often attributed to healthy agriculture and energy sectors, its construction and manufacturing sectors are relatively healthy and the state has seen 42% job growth in professional and technical services and 36% in management of companies since 2002. North Dakota is the top job performer since the 2007 peak and is fifth since 2000. The state also places first in growth in GSP per job (productivity increase), second in GSP growth and third in per capita income growth. Recent investments in research and development (R&D) infrastructure are beginning to pay off as the state is the fastest growing in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) job growth.

- Virginia – Already a professional and technical services powerhouse in 2002, Virginia added another 135,000 jobs in that sector since that time, fueled by 90,000 new jobs in computer systems design and management and technical consulting services. The state’s high incomes and slightly below average cost of living placed it first on our cost of living adjusted family income measure.

- South Dakota – South Dakota is a strong overall performer, doing best in productivity and output measures. Partly due to an enterprise-friendly regulatory structure, the state has 30% more finance industry employment than the national norm and has added 18% growth in finance employment since 2002. The state’s manufacturing sector actually gained jobs since 2002, led by growth in signs, chemicals, communications equipment, and construction equipment, all averaging more than $43,000 in earnings per worker.

- Maryland – Maryland landed in the top 20 or better on all seven performance metrics. Maryland saw strong growth in technical consulting and computer systems design, but especially private scientific research and design services, a sector more than 2.5 times as concentrated in Maryland than the nation as a whole and paying nearly $95,000 in earnings per worker.

- Wyoming – Wyoming’s growth is powered by a rapidly expanding energy cluster, which added more than 18,000 jobs since 2002 and now holds 30% of all employment in the state. The energy growth has spilled over into business services sectors such as environmental consulting, surveying and mapping, and testing laboratories. Its overall manufacturing supersector also gained jobs, seeing the fabricated metal and electrical equipment clusters begin to emerge.

- New York – While New York saw average job growth through the beginning of the decade, it has weathered the recession better than most other states, and its high productivity and productivity gains help place it among our top performers. Accounting for about 8% of all jobs in the state, the professional and technical services sector added more than 115,000 jobs for 15% growth.

- Texas – Texas has seen strong job growth this decade and has weathered the recession well, fueled by 20% expansion of a now 1.1 million job energy cluster. Recently machinery manufacturing and transportation equipment manufacturing clusters are emerging, both growing to more than 90,000 jobs. This has helped stimulate a 15% expansion in transportation and logistics including warehousing and storage and many freight and specialized trucking sectors.

- Iowa – A solid performer across most of our metrics Iowa’s strength is perhaps in its stability. The state’s largest cluster, agribusiness, food processing and technology, grew at a 1% rate since 2002, significantly better performing than the same group of industries nationally. Iowa’s other most competitive clusters include machinery manufacturing (farm and construction equipment, refrigeration and heating systems, and other commercial equipment) transportation and logistics, and advanced materials (search and navigation equipment and machine shops).

- Nebraska – Nebraska has added 15,000 jobs to its business and financial services cluster since 2002, led by management and technical consulting, management of enterprises, and credit intermediation, all adding at least 3,000 jobs and averaging $55,000 to $90,000 in earnings per worker. The state’s railroads and support industries and freight trucking support a strong transportation and warehousing cluster, and the state has seen a boom in marketing consulting and market research sectors.

- Montana – While Montana’s energy and mining clusters added a combined 8,400 high-paying jobs to the state since 2002, Montana’s greatest source of national dominance came from the collection of arts, entertainment, recreation, and visitor industries, perhaps a sign that the rest of the nation is beginning to discover the Big Sky country. Montana is also beginning to see the emergence of smaller clusters in chemicals, apparel and textiles, and fabricated metal products.

Growing Jobs: How Do They Do It?

A review of which states are high performing shows a diverse group—some big, some small; some rural, some urban; some inland, some coastal—but a closer examination shows a shared pattern of policies by these high performers.

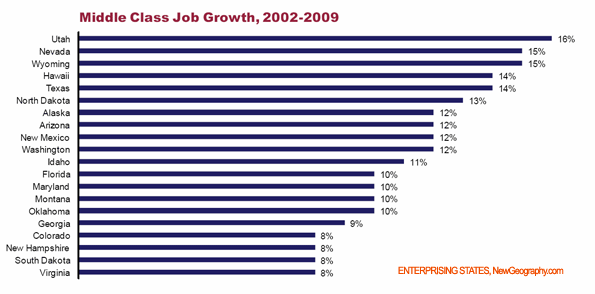

There is no such thing as single a silver bullet strategy for job creation. Among our top ten performers, all ten have seen at least 4% job growth since 2002 in mid-level jobs requiring at least long term on-the-job training but less than a four-year degree. Five of the ten states increased those jobs more than 10%. At the same time all ten increased science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) jobs by at least 4% over the same period, with 7 of 10 growing STEM jobs at least 14%.29

An assessment of top performing states, regardless of by what measure, eventually gets down to a state’s ability to execute successful initiatives. Aside from minding the basics of primary education and supportive infrastructure, success begins with an understanding of a state’s economy and demographics, including its strong points and its gaps. States that can mobilize the relevant partners to put together the strategic networks to build upon those strengths while addressing the weaknesses will be winners in the long run.

Adequately financing any initiative is paramount to its success. Top performing states have come up with winning formulas often based on combining state funding with federal programs and private sources. As regional workforce skills gaps become more acute, non-governmental agencies and private enterprises more are willing to join new collaborative development projects.

Programs such as Kentucky’s “Bucks for Brains” which requires universities to match state funds with donations from philanthropists, corporations, foundations, and other non-profit agencies, or Florida’s use of American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funding in combination with existing state funds to tackle major infrastructure programs illustrate unique solutions to sufficiently financing winning initiatives.

Examples of strong partnerships featuring open communication are especially evident in high performing export states. Export programs are based upon effective communication between the importing country, the exporting manufacturer or business, and the state program helping to facilitate the connection.

The TexasOne program creates promotional materials to market the state and its manufacturers to importing countries and leads trade missions to importing countries and hosts reverse trade missions to the state. Nevada works with a network of trade representatives in targeted markets throughout Asia, North America and Europe, focused on cultivating distribution channels and facilitating opportunities for foreign direct investment in Nevada enterprises.

Many high performing states offer an array of corporate, manufacturing, and land tax programs. So too, many states are shying away from direct subsidies for promised job growth in favor of highly targeted tax credit programs that require direct investment by the firm or venture investors wherein the tax benefits are only realized after new jobs are in place. Other credit programs target historically underdeveloped geographical regions.

Other states such as North Dakota, Florida, and Mississippi have turned to comprehensive tort reform as another key element enterprise-friendliness. Whether these reforms are specific to a particular industry or issue, they ultimately help businesses, large and small, remain competitive and free of excessive burdens from excessive litigation.

Private sector and academic collaboration is one of the most readily identifiable attributes of high performing states across all measures. Whether it is successful innovation and entrepreneur programs such as Montana’s TechRanch, Oregon’s Innovation Council, Rhode Island’s Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, or job creation and economic development initiatives such as Momentum Mississippi, these private and academic partners are providing critical input, oversight, and resources to bolster the effectiveness of state efforts.

Many states are locating business incubators adjacent to universities in partnership with the schools while others are building laboratory spaces and other specialized infrastructure to offer to growing companies on an a la carte basis. In either case, this business and scientific infrastructure can reduce start-up costs for new enterprises and provide students the chance for experiential learning while earning their degrees.

While there are obviously other policies or initiatives that high performing states share there are some commonalities: building on momentum; delivering adequate funding for initiatives; developing strong relationships and communication strategies; enterprise-friendly tax and regulation systems; and vigorous collaboration between business, government, and education institutions.

Praxis Strategy Group is an economic development, analysis, and strategic planning firm. Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and author of The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050