This is the second in a two part series exploring a pessimistic and an optimistic future for the United States. Part One appeared yesterday.

A positive assessment of US prospects rests on at least seven propositions. First, the current crisis is not inherently more threatening than many others, most notably the Civil War, the Great Depression, and two World Wars. Quality leadership, building on the resilient political and economic institutions of the country, will prove sufficient to bring about needed sacrifices and transformations. We have seen this many times in the past from the Progressive Era to the New Deal, the Second World War and the winning of the Cold War, which was a uniquely bipartisan triumph.

Second, despite the ongoing problems of racial inequality and tensions about immigration, the United States has been uniquely successful in having peacefully achieved a truly multi-racial and multi-ethnic state. It has welcomed waves of diverse immigrants, and integrated them into a broader, ever changing society. This process has culminated symbolically and literally in the election of a multi-racial president, Barack Obama.

Third, economic corruption and financial crises have been recurring phenomena, and the nation has emerged out of these because of the sheer magnitude of talent and natural resources. This has been aided by a deep entrepreneurial capacity and willingness to take risks, and, overall, a willingness of most to work hard to improve life for themselves and their families.

Fourth is the existence of a large and literate population, willing to work, certainly the world’s finest university system and research establishment, over and over again engendering innovations that create future economies: e.g., the computer revolution. American secondary education is still in need of great improvement, but the US University remains a beacon to talent from around the world.

Fifth, despite the noise and uproar, despite the continuing clash between the traditional and the modern or secular, the nation, through its independent courts and helped by governmental decentralization, e.g. the Federal system, the country remains the freest society in human history. Despite the appearance of power of the religious right under the Republicans since the 1970s, serious erosion in freedom of thought has been kept to a minimum. Similarly, the cult of political correctness, although annoying, has become, if anything, less potent and increasingly the butt of jokes.

Sixth, and perhaps most important, we have to consider demography. Despite current unemployment and despite the imminent retirement of the baby boomer generation, the United States, alone among the richest economies, will continue to have a relatively favorable ratio of wage earners to the elderly. This will enable us to afford social security and Medicare. The new generation – known as millennials – will constitute a large source of new labor, innovation and entrepreneurs needed to propel our economy.

Finally, there are a few positive trends, including modest recovery in housing and in auto sales, hints of some pulling back from the out-sourcing of services, and continuing innovation and marketing of new products and services. On the political side, although the current anti-incumbent mood will likely reduce Democratic margins in Congress and in several states in 2010, the sheer lunacy of the “tea party“ activists, many of them unreconstructed “know nothings” may actually hurt the Republican party more than the Democrats. People are constantly being reminded why, for all the failings of the Democrats, they tossed the Republicans from power in the first place.

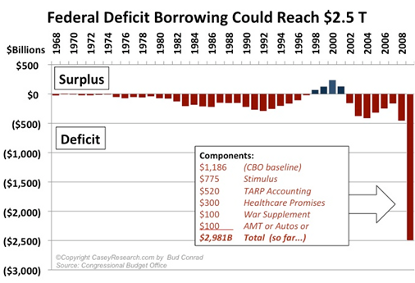

An optimistic scenario rests on the historical precedent of muddling through crises and then creating new waves of innovation in products and services, and on the presence of a large labor force willing and able to work. A vital question is whether the President and Congress will have the courage to ask voters to make short-term sacrifices: higher income taxes on the rich and reduced subsidies to entrenched interests across the board that will be needed to restore fiscal health. And finally there is the big question, are the American people ready to do with less today to build a better future for the next generation?

Richard Morrill is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Washington. His research interests include: political geography (voting behavior, redistricting, local governance), population/demography/settlement/migration, urban geography and planning, urban transportation (i.e., old fashioned generalist).

Photo: elycefeliz