‘How shall we live?’ is a question that naturally concerns architects, planners, community representatives and all of us. It is a question that turns on the density of human settlements, the use of resources and the growing division of labour.

Where Europeans lived mostly in the countryside in the eighteenth century, by the middle of the nineteenth century they had gathered in burgeoning towns and cities. The divide between town and country became a worldwide template in the twentieth century, as nations measured their economic growth by the pace of urbanisation. Today, more and more of the world’s population live in cities. In 1970, 35 per cent of the world’s population lived in urban environments; today that number has passed fifty per cent.

The passage of people from the countryside to the city, though, was not the end of the great movement of peoples in the developed world. The developing world continues to urbanise, but North America and Europe started to move in the opposite direction in the 1920s, away from city centres outwards into new suburbs. Humanity, it seemed, was on the move again, and by the 1970s more Americans lived in suburbs than in cities or in the country.

European cities, too, saw the growth of suburbs, as first wealthy people, and then later working people moved away from city centres, taking advantage of new railway and tramlines, and then later motorways, to commute to work, and return to homes beyond the urban boundary line. All these have been in one way or the other supported by governments.

Roosevelt’s government Homeowners Loan Corporation, the Federal Housing Administration and then later the Veterans Administration provided cheap mortgages with fixed term repayments and a low interest rate. After World War II the rise continued, and by 1972 the FHA had helped nearly eleven million families to own homes. In those same years between 1934 and 1972, the percentage of American families living in owner-occupied dwellings rose from 44 per cent to 63 per cent.

Between 1920 and 1930, when automobile registrations rose by more than 150 percent, the suburbs of the nation’s largest cities grew twice as fast as the core communities. Henry Ford said at the time ‘The City is doomed’ and that ‘we shall solve the city problem by leaving the city’. In 1956, the Interstate Highway Act created the largest freeway system in the world.

In Britain, the postwar government planned and built garden suburbs and new towns, ringing London, on schemes first outlined by Ebenezer Howard at the end of the nineteenth century. Similar ‘garden cities’ were built in places like Hellerau, outside Dresden (1909) and Kapuskasing and Walkerville in Ontario, Canada.

The reflux of people in the more developed world, away from the city centres, strains our distinctions between ‘city’ and ‘suburb’. The suburbs of the previous generation are the urban centres of the present. The dense settlements of Notting Hill, New Jersey and Sarcelles are the suburbs of twenty, fifty or a hundred years ago. As suburbanisation carries on, people are moving away from the suburbs their parents moved into, with much the same motives of seeking greener pastures or fleeing urban problems. New words are coined to describe the change: exurbs, edge cities, edgelands.

This pace of suburbanisation has provoked its own anxieties. The great historian of ‘sprawl’, Robert Bruegmann, identifies three distinctive ‘anti-sprawl’ movements. In the 1920s Britain, intellectuals and Tory shire-dwellers raised a great protest against ‘ribbon development’ and what they condemned as ‘bungaloid growth’. In the late 1950s William H. Whyte, a journalist at Fortune magazine warned that ‘huge patches of once green countryside have been turned into vast, smog-filled deserts – at a rate of some 3000 acres a day’.

Today suburbs are no longer just gauche or racist; they are killers of the planet. Herbert Girardet’s idea of the ‘human footprint’ was that each head of population would need a given area of land from which to raise his or her subsistence. As the mass of consumer goods each person used increased, he would need more land – the footprint would get larger. Indeed, says Girardet, if all the world lived at London rates of consumption, they would need three planets to sustain them, around 40 billion hectares, rather than the 14 billion hectares of landmass on our earth.

Often ignored in such discussions is the fact that as consumption has grown, even more so has productivity. Across the world the land given over to grain harvesting shrunk from 732 million hectares in 1981 to 656 million in 2000 (after growing solidly from 587 million in 1950), even though the world population kept rising. That is because yields grew faster than consumption, releasing land from cultivation. Over the same years, grain yields from each hectare grew from 1.1 tons to 2.7 tons.

This efficiency has done much to keep green land, well, green. We are seeing not deforestation but aforestation. In the United States forestland is growing 5886 square kilometres on average every year. In the European Union forests are growing 1428 square kilometres every year. And as farm land is retired, ever more land is protected in national parks worldwide.

Much of the critique of the suburbs revolves around the car. The intrinsic link between suburbs and cars has many social consequences, but first and foremost it has consequences for energy use and globe-warming CO2 emissions. In thousands of ways, the more dispersed life of the suburbs would seem to be a much greater drain on resources than a more compact life in densely occupied cities.

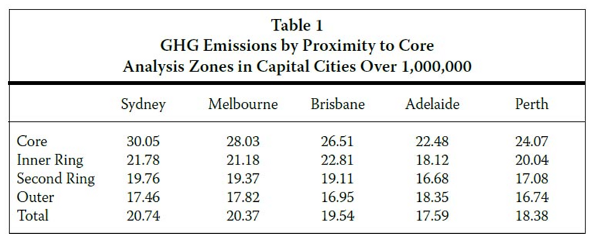

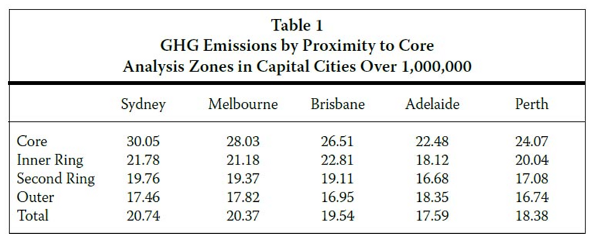

However, there is evidence that runs counter to our expectations of the association between settlement densities on the one hand, and energy use and greenhouse gas emissions on the other. Analysis of the Australian Conservation Foundation’s Conservation Atlas prepared for the Residential Development Council shows, surprisingly, that per capita greenhouse gas emissions are lower in suburban areas than city centres.

Source: Greenhouse gas emissions, tonnes per capita, Housing form in Australia and its impact on greenhouse gas emissions, Residential Development Council 22 October 2007, p 11

There are a number of reasons why this should be the case. First, suburban dwellings are often newer, incorporating more energy efficient means and materials – notably, better insulation. Second, though car journeys are less greenhouse gas efficient by the kilometre, the difference is not so great, and public transit is less efficient in other ways (because it rarely takes you just where you need to go) creating extra journeys and more waste.

What is more, the view that suburban commuting must be a greater producer of greenhouse gas emissions does not take into account the changing patterns of home and work location in the newer suburbs. Our model of the diurnal commute, into the city in the morning and back to the dormitory town at night is becoming less typical.

For many people, commuting is quicker in the suburbs than in cities. It takes residents within the suburbs and exurbs 24/25 minutes, much less than the 43 minutes for those living and working in Greater London. The case for reducing energy use by living at higher densities appeals to our common sense, but less dense living might provide answers to the problems of energy and emissions.

Suburbanisation has raised fears of social division. Anxieties about social alienation, along with those about the environment, fit into a wider account of the problems of suburbanisation, and a proposed solution, which has been called the New Urbanism.

One group that hoped to address the problem are the New Urbanists, a group of architects and planners who have turned the perceived problem of the suburbs around and created a manifesto to reverse those negative trends. Among the best-known exponents of the New Urbanism is Peter Calthorpe, for the arguments in his books The Next American Metropolis (1993) and Sustainable Communities (with Sim Van der Ryn, 1989).

Calthorpe argues that we are still building suburbs that are ‘increasingly out of sync with today’s culture’ failing to take into account changing household composition, falling incomes and environmental concerns – a proposition that many American “progressives” held to be strikingly confirmed by the collapse of the US housing market in 2008/9, and its wider impact on the economy.

Intriguingly, Calthorpe’s views on planning take us far away from technical considerations into an idea of what the good life ought to be. Calthorpe says that ‘we need to start creating neighbourhoods’, arguing that, ‘Our faith in government and the fundamental sense of commonality at the centre of any vital democracy is seeping away in suburbs designed more for cars than people, more for market segments than communities.’

The New Urbanists were an influence on Britain’s Urban Task Force, under Lord Rogers of Riverside, who drew up the British government’s planning policy in the document Towards an Urban Renaissance in 1998. Rogers, too, favoured higher densities, mixed use and an end to suburban sprawl.

Folding the idea of preserving our social capital into the broader ideas of environmentalism, New Urbanists, the Urban Task Force and Herbert Girardet have all gravitated towards a concept of ‘sustainable communities’. It is a concept that is at once recognisable and at the same time very vague. Still, it has been an enormous influence on policy makers, who have tried to give substance to its implications.

However, the evidence is clear that despite the many policy initiatives that have been taken to create ‘sustainable communities’, developers, and perhaps consumers, too, have resisted the appeal. First, take the case of Europe. Analysis of 42 west European cities shows that in all but one (Berlin) the suburbs and exurbs are growing faster than the core.

In 1965 44 million people lived in the center of these 42 cities, while 42 million lived in the suburbs and exurbs. By 2000, the inner city population had dropped to 39 million, while the suburban had grown to 71.6 million. On average, inner city populations declined by 13 per cent, while suburban and exurban populations increased by 113 per cent.

- For example Madrid’s inner city population grew from 2.25 million to 2.4 million between 1965 and 2000, but its suburbs grew from 125,000 to 2.1 million.

- Over the same period, Frankfurt’s inner city declined from 695,000 to 641,000, while its suburbs grew from 755,000 to 1.25 million

- Brussels’ inner city shrunk by 30,000 to 137,000, while its suburbs grew from 1.8 to 2.3 million.

- Even Barcelona, poster-boy for urban densification, saw its core decline from 1.6 million in 1965 to 1.5 million in 2000, while its suburbs grew from half a million to 2.26 million over the same period.

Source: Western Europe: Metropolitan Areas & Core Cities 1965 to 2000/2001, Demographia, http://www.demographia.com/db-metro-we1965.htm.

Policies that try to contain sprawl run against the grain of human nature. Many, even most people aspire to live at lower densities than they do right now.

Still, there is a point to the Urban Renaissance. The gentrification of canal and riverside districts, and the creation of ‘cultural quarters’ is a well-documented trend. This was the sense in which there was an urban renaissance in the noughties: well-heeled yuppies took back parts of the inner city. Often single, they had less need of gardens and preferred loft living in Shoreditch or central Zurich to a detached house in the Suburbs, which were coming to be less exclusive, anyway.

These developments should lead those polemicists painting the suburbs as the greedy well-to-do and the inner cities as disproportionately occupied by the suffering poor to recalibrate their argument. Tim Butler, Chris Hamnett and Mark Ramsden’s analysis of London’s employment in the 2001 census shows that outer London and the South East is more working class than inner London.

The image of black inner cities and white suburbs is changing, too. Many major cities are suffering ‘black flight’ as black Americans move out to the more affordable suburbs: Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, Dallas, San Diego, Washington and Oakland. San Francisco’s black population is down from 13.4 to 6.5 per cent.

Not only do the New Urban policy prescriptions coincide with the recent gentrification of inner cities, there is some evidence that they have helped it. Portland, where the adoption of an urban growth boundary (or green belt) was intended to densify the city and protect the country, has seen house prices rise much faster than the national average (it was below that, now it is above). Inside Oregon’s protected ‘farm land’ many farmhouses turn out to be just country homes for the wealthy disguised as farms

To show that Greenwich Millennium Village was not just more riverside yuppie flats, but a real community, architect Ralph Erskine built in a combined school and health centre, except that an old school, Anandale, had to be relocated from the centre of Greenwich to the peninsula to provide the children – and spookily, it has kept its old catchment. Erskine’s Potemkin Village recruits children from Greenwich to act the part of the local community. A few parents objected at first, but most changed their minds when they saw the quality of the facilities. Around ten of the families in the Village proper send their children there, and of those, the majority are in the 20 per cent of new homes that earmarked for social housing. Like other attempts to reinvent the village in the town, such as the Bo01 estate in Malmo, Sweden, Erskine’s Greenwich peninsula is overwhelmingly upper middle class.

It is pointed that in Britain, where, thanks in part to Lord Rogers, planning restrictions on new development were greatest, there was no boom in housebuilding, unlike much of the rest of the world. Of course there was a boom in house-prices – quite a phenomenal one. But all through the period 1997 to 2008 house-building fell below the rate needed to replace Britain’s dilapidated housing stock.

The New Urbanism was always rather more than an architectural style, but also a vision of the good life. It hoped to address the social divide, and the solipsistic withdrawal from city life. Curiously, it seems if anything to have played a part in accelerating the social divide, in particular the gentrification of inner city enclaves. Far from making the city more diverse, the new urbanism seems to be making it more uniform. In London the trend towards in-fill by building on brownfield land has had the unintended effect of the loss of green spaces in the City. In the north of the city, Londoners gathered to protest at the recreation of urban overcrowding, when Islington’s municipal authorities planned to force yet another apartment block on top of garages in Pilgrim’s Way.

The New Urbanism was always rather more than an architectural style, but also a vision of the good life. It hoped to address the social divide, and the solipsistic withdrawal from city life. Curiously, it seems if anything to have played a part in accelerating the social divide, in particular the gentrification of inner city enclaves. Far from making the city more diverse, the new urbanism seems to be making it more uniform. In London the trend towards in-fill by building on brownfield land has had the unintended effect of the loss of green spaces in the City. In the north of the city, Londoners gathered to protest at the recreation of urban overcrowding, when Islington’s municipal authorities planned to force yet another apartment block on top of garages in Pilgrim’s Way.

The New Urbanism describes one trend in society, the gentrification of inner cities. But many more people want to move outwards, to cheaper and more spacious homes. As communications improve, and more land is released from farm use by rising agricultural productivity, that shift towards more dispersed dwellings should find its place in architecture and planning theory, too.

Ultimately more dispersed patterns of living lead to more dispersed commuting.

South East England, the Bassin Parisien, Central Belgium, the Dutch Randstad, Rhine-Ruhr, Rhine-Main, Northern Switzerland, and Greater Dublin are examples of what geographers call polycentric urban regions. When industry moves out of monocentric cities, it disperses along valleys and communication lines.

But the growth of Mega City Regions does not mean the countryside is all being concreted over. On the contrary, these economic regions are a lot greener, a lot more dispersed than the twentieth century city. Exurbs and edge towns are being populated in the yawning green spaces in between the industrial estates.

The issue that needs to be addressed is: Can We Imagine A Dispersed Future?

Far from being necessarily de-humanising, dispersed settlements are an opportunity for an enlargement of the human spirit. To imagine that there is anything in physical proximity that is essential to community is to confuse animal warmth with civilisation, and an unfortunately deterministic view of architecture’s relationship to society. But worst of all it misses out the great alternatives that are waiting to be made in new communities across the country.

James Heartfield is author of Let’s Build! Why we need five million homes in the next ten years, and a director of www.Audacity.org.

The New Urbanism was always rather more than an architectural style, but also a vision of the good life. It hoped to address the social divide, and the solipsistic withdrawal from city life. Curiously, it seems if anything to have played a part in accelerating the social divide, in particular the gentrification of inner city enclaves. Far from making the city more diverse, the new urbanism seems to be making it more uniform. In London the trend towards in-fill by building on brownfield land has had the unintended effect of the loss of green spaces in the City. In the north of the city, Londoners gathered to protest at the recreation of urban overcrowding, when Islington’s municipal authorities planned to force yet another apartment block on top of garages in Pilgrim’s Way.

The New Urbanism was always rather more than an architectural style, but also a vision of the good life. It hoped to address the social divide, and the solipsistic withdrawal from city life. Curiously, it seems if anything to have played a part in accelerating the social divide, in particular the gentrification of inner city enclaves. Far from making the city more diverse, the new urbanism seems to be making it more uniform. In London the trend towards in-fill by building on brownfield land has had the unintended effect of the loss of green spaces in the City. In the north of the city, Londoners gathered to protest at the recreation of urban overcrowding, when Islington’s municipal authorities planned to force yet another apartment block on top of garages in Pilgrim’s Way.