Much has been made of California’s struggles, but some still say California’s best days are ahead of it. In this calculus, innovation in high tech, biotech, green tech, clean tech, any tech will ultimately pull the state out of its current funk and to even greater success tomorrow. Promoters of this view cite an impressive roster of statistics around venture capital, patents, new business formation, etc., along with obligatory anecdotes of ambitious new startups with world changing products (coming soon) and their slick, dynamic founders. This view reached its apotheosis in a Time magazine cover story called “Why California Is Still America’s Future”.

This view of the world is correct – but incomplete in a fundamental way. These emerging industries are in many ways the future of America, and they all have their creative epicenter in California. But they aren’t generating many net new jobs there.

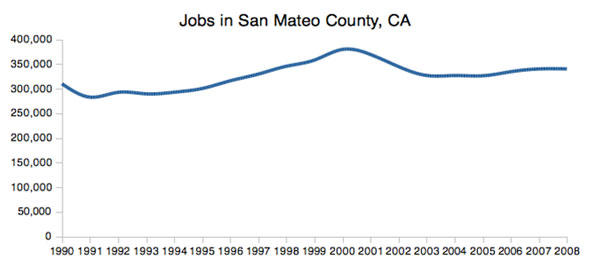

Let’s consider the counties that make up the heart of these industries. Silicon Valley’s San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties both experienced slow job growth between 1990 and 2009. San Mateo County only added 30,000 net jobs, an average of less than 1,700 new jobs per year, or a compound annual growth rate of 0.5%.

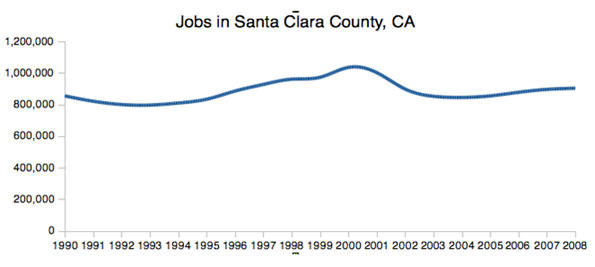

Santa Clara County added around 50,000 jobs over that 18 year period – about 2,700 jobs per year, but only a CAGR of only 0.3%.

Both counties added significant new jobs in the late 90s, but these were lost when the dotcom bubble collapsed. The recovery from that decline only reached back to the levels just before the early 90s recession, continuing the long running Silicon Valley boom-bust cycle. Silicon Valley actually added jobs at a slower rate than California as a whole during this period.

You can see the employment impacts just driving down the 101 freeway; there are more than 43 million square feet of unoccupied space, the equivalent of 15 Empire State Buildings. Twenty one percent of “Class A” space and low rise flex space – used for high-tech research and development – is empty. Unemployment overall in Santa Clara county hovers around 12%, substantially over the national average.

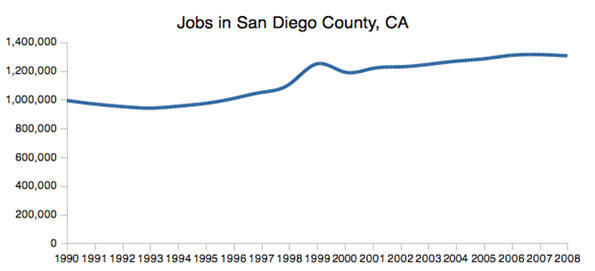

San Diego County, one of the key centers of the biotech industry, did much better, adding 310,000 jobs over the same timeframe. This is over 17,000 jobs per year, or a CAGR of 1.53%, much better than Silicon Valley, but hardly enough to reflate California’s job market. For example, Los Angeles County added almost a million people during this time, but actually lost jobs.

A critical consideration may well be that the future could be different from the past for these industries, and that over the next 20 years they will generate far more jobs than in the previous. But the evidence seems to be the other direction.

California clearly has no shortage of dynamism in high-end economic sectors. There are still plenty of new innovative firms being founded in California or even moving there. And it seems likely these firms will continue to generate significant wealth for the state in the future. Given its current tax structure, the state treasury has significant “operational leverage” to the upside here. Another strong recovery cycle might even replenish the state’s coffers, though won’t offer solace for some time at least.

But these industries won’t generate many net new jobs. And that is becoming the problem in both Silicon Valley and the state.

Therein lies California’s dilemma. The ability to generate large amounts of wealth on a narrow job base isn’t enough to support a state of 37 million people. Brazil generates enormous wealth too, and supports lavish stores like Daslu, where you can’t walk in off the street, but there’s a helipad on the roof – and a favela just down the street. But Brazil doesn’t have a middle class economy.

With innovation the watchword of the day, and no other realistic prospects available in the near term, it is easy to see why places from California to Michigan are placing their hopes on such high end information age jobs. Unlike most, California is already winning the war for the highest value jobs and talent in the space. The headquarters, R&D, core software development, design, and prototyping will be done in California. But it is unlikely to be where the manufacturing, customer support, sales, warehousing, back office support, and other core functions get done. And those are where the jobs are. The back of the iPhone says everything we need to know. “Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China.”

California is clearly right to make these industries a priority. The danger is that it comes to focus on them so exclusively that it implements policies that are overly favorable to those select functions, but hostile to everything else. California needs to make sure it has a strategy for middle class and working class jobs beyond the low end service sector. That’s a much harder problem than maintaining Silicon Valley’s dominance, but it’s clearly at least equally as important. The high end portion of various “tech” sectors alone are never going to provide enough jobs to secure a prosperous future for the vast majority of Californians.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.