The recession may have slowed the pace of net migration, but the essential pattern has remained in place. People continue to leave places like New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles for more affordable, economically viable regions like Houston, Dallas, Austin and San Antonio. Overall, the big winners in net migration have been predominately conservative states like Texas–with over 800,000 net new migrants–notes demographer Wendell Cox. In what Cox calls “the decade of the South,” 90% of all net migration went to southern states.

Blog

-

Contributing Editor MICHAEL LIND on Which Way California? regarding Clinton

The Clintonites were wrong. The “new economy” was an illusion. Neoliberals have to admit that before they can stop the bleeding.

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN in the NY Times regarding decline

If you read them carefully, you’ll notice that their visions aren’t entirely incompatible. Kotkin focuses on America’s enduring economic strengths: Our demographic balance (which compares favorably to Europe and Asia alike), our still-vast natural resources, our entrepreneurial culture, our ability to assimilate immigrants, and so on. Deneen emphasizes the weakening of our liberal political order, with its threefold emphasis on liberty, equality and prosperity.

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN on NJ.com regarding Texas/California

The same goes for Joel Kotkin as regards his home state of California. Kotkin, who is a fellow at Chapman University and executive editor of NewGeography.com, was quoted in the article comparing high-tax California to low-tax Texas. A couple of decades ago, he said, services in Texas were noticeably inferior to services in the California. “Today, you go to Texas, the roads are no worse, the public schools are not great but are better than or equal to ours, and their universities are good,” he was quoted as saying.

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN on The Press Enterprise regarding Riverside

Joel Kotkin, a Chapman University fellow focused on urban planning, said he doubts anyone wanting the urban experience of living downtown would flock to Riverside instead of true urban centers. People have historically moved to the Inland region for the opposite of condo-living: a single-family home with ample space.

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN on the NY Times regarding Sonoma

“The danger is that a slow city ends up as a city for the geriatric rich and the trustafarians,” said Joel Kotkin, an urban analyst and author of “The City, a Global History.”

-

Beyond Neo-Victorianism: A Call for Design Diversity

By Richard Reep

Investment in commercial development may be in long hibernation, but eventually the pause will create a pent-up demand. When investment returns, intelligent growth must be informed by practical, organic, time-tested models that work. Here’s one candidate for examination proposed as an alternative to the current model being toyed with by planners and developers nationwide.

Cities, in the first decade of this millennium, seem to be infected with a sort of self-hatred over their city form, looking backward to an imagined “golden era”. The most common notion is to recapture some of the glory of the last great consumerist period, the Victorians. During this time, from the 1870s to the early 1900s, many American towns and cities were formed around the horse-drawn wagon and the pedestrian. This created cities with enclaves of single-family homes and suburbs that seem quaint and tiny in retrospect to today’s mega-scale subdivisions and eight-lane commercial strips.

One bible for the neo-Victorians was “Suburban Nation,” a 2000 publication seething with loathing and anger over urban ugliness. In a noble and earnest effort to repair some of the aesthetic damage, the writers proposed a grand solution. Their goal was essentially to swing the development model back to the era of the streetcar and the alleyway, the era when cars were not dominant form-givers and families lived in higher density and closer proximity.

In the last decade, this movement gained traction with hapless city officials often tired of hearing nothing from their citizens but complaints over traffic and congestion. They embraced the New Urbanist movement which promised to turn the clock back to an era of walkable live/work/play environment of mixed neighborhoods. In the new model, the car would at last be tamed.

Yet, looking at most of these communities, the past has not created a better future. More often they have created something more like the simulated towns lampooned by “The Truman Show”. These neo-Victorian communities ended up with some of the form of that era, but devoid of employment and sacred space. They also created social schisms of low-wage, in-town employers and high-salary, bedroom community lifestyles marking not the dawn of a new era but the twilight of late capitalism as the service workers commute into New Urbanist villages while the residents commute out.

Meanwhile, planners who believe that practical design solutions and the vast quantity of remnants from the tailfin era are “almost all right” have remained quietly on the sidelines. This silent retreat, a natural reaction, now puts many good places in jeopardy as the activist planners try to “fix” neighborhoods and districts that were not broken to begin with. We risk losing some of the important postwar building form that well serves the needs of its users and, rather than being blacklisted, should be held up as a valid, comparative model for use by developers seeking to build good city form when the pent-up development demand returns.

It is time to hit back. Midcentury modern – the era from about 1945 to 1955 – has become a darling style of the interior design world, has yet to be recognized as a valid model for urban development. For too long, neighborhoods built in this era have been treated poorly by the planning community. Yet this period created a critical transition between the archaic beloved streetcar suburbs and the 1980s commercial car-must-win planning. They provide a valuable, forgotten lesson when the middle class’s newfound prosperity was expressed by low-density, car-oriented mixed-use districts that were still walkable and expressed through their form a certain heroic optimism about the future.

With building fronts set back just enough for parking, yet still close together to give a pleasant pedestrian scale, these little districts remain abundant in the landscape of our towns and cities – nearly forgotten in the fight over form, perhaps because they are doing just fine. They were built when everyone was encouraged to get a car, but before the car became a caveman club pounding our suburban form into big box “power centers” and endless, eight-lane superhighways of ever-receding building facades. These districts were developed before the local hardware store was replaced by Home Depot and many remain intact, thriving, and chock-full of independent business owners. Many of these are true mixed-use districts – with light industrial, second floor apartments, retail and other uses peacefully coexisting.

In small commercial districts developed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, a balance was struck between the traditional town form and the car, a balance that has been forgotten in the planning war being waged today. This era produced many neighborhoods and districts that are “almost all right”, in the words of noted Philadelphia architect and thinker Robert Venturi, when defending Las Vegas to the prissy academic community.

To go right to a case study, take the Audubon Park Garden District in Orlando, Florida. Adjacent to Baldwin Park, a Pritzker-funded New-Urbanist darling of 2002, this district is a vintage collection of mixed-use commercial, residential, and industrial buildings constructed in the 1950s. Set back from the curb approximately 42 feet, the mostly one-story storefronts allow parking in front yet are visible and accessible to pedestrians. The car is accommodated in the front of the store, making access easy and convenient, yet the pedestrian can walk also from place to place without long, hot trudges. Drivers see the storefronts. Scale is preserved. (See attached file for street elevations).

The architecture, instead of recalling nostalgic, Victorian styles, is influenced by the art deco and populuxe styles of the Truman era, when America was united, self confident, and victorious. And the businesses reflect an organic mix serving neighborhood needs, their storefronts and facades created by themselves, not by some Master Planner, theming consultant, or fussy formgiving designer. Here, one finds customers in dialogue with shopkeepers, blue collar and creative class mixed together, a few apartments over their stores, and a localism that has endured for fifty-odd years, largely forgotten because it works.

Places like this three-block district, and others like it, need to be championed. Decoding just what works here, and how it elegantly accommodates the car and the pedestrian, is critical to counterbalance the coercive impact of the New Urbanist movement and present a working model to future developers.

When New Urbanism was a fledgling movement, it represented a necessary alternative to car-dominated planning principles, and offered a choice where there previously was none. Today, the rhetoric of this movement has sadly forced out all other choices and emphasized one form – that of the streetcar era – over all others. This increasingly authoritarian movement shuts out all other choices today, and now threatens places like Audubon Park with its singular vision by sending in planners to “workshop” an ideal, Victorian makeover. Such actions, if implemented, will destroy the healthy, functioning connective tissue that makes up vast portions of our urban environment for the sake of a romantic notion of form over substance.

Instead of enforced, and often overpriced, nostalgia, we would do better to seek out districts planned after the car and have worked through time, and hold them up as valid choices to implement when planners are considering a development. These districts, whether a single building, a collection, or a whole community, will become important models as the pendulum swings back from the extremes that it reached by 2007 and 2008.

For too long, planners and developers have chosen to be silent in the face of the often strident rhetoric espoused by “smart growth” and New Urbanist ideologues. Meanwhile, a tough analysis of New Urbanism’s successes has yet to be seriously undertaken, and alternative models presented. Cities across the nation are considering a move to form-based codes which would lock out districts like Audubon Park and doom existing ones to Victorian makeovers. Useful, diverse and workable places will be destroyed to fit a “one size fits all” ideology.

So before midcentury modern becomes just another furniture style, a window of opportunity exists to fight back. These kinds of districts dot the cities and towns of America and deserve to be held up as alternative models for new development. Instead of a dogmatic slavishness to nostalgia, planners and developers need to stand up to the preachers of preapproved form, and look for multiple solutions for future urban form. Smart growth should not supersede the arrival of a more flexible, diverse approach of intelligent growth.

Richard Reep is an Architect and artist living in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

-

Counting Counties

I was about seven years old when I got my first copy of the Rand McNally Road Atlas (RMRA), and I’ve rarely been more than 50 feet away from one ever since. Unless I was out of the country, there has probably never been a day when I haven’t looked at it at least once.

The obvious question that a kid would ask is: What is the smallest county in the United States? In those days, RMRA alphabetized counties separately from cities and towns in the index, so it was a simple matter to go through and search for the smallest one. But I didn’t have the patience to sort through all 50 states; instead I tried to use some cleverness.

I assumed that the smallest county would not be in populous states, so I excluded places like California and New York. Further, the RMRA didn’t list any counties for Alaska (nor does it today), so that state didn’t count. Thus the logical choice (for a kid) was Wyoming – the least populous state in the union (then excluding Alaska). But I soon noticed that Wyoming only had 23 counties – so despite the small overall population, it seemed unlikely that any of them were very small. Indeed, Wyoming has no counties with fewer than 1000 people.

So the trick was not only to find a sparsely populated state, but also one with a lot of counties. North Dakota, with less than 700,000 people but with 53 counties, fits the bill. And indeed, I came across Arthur County, population 444, which seemed a likely candidate.

But South Dakota has 66 counties and Nebraska 93, so it is possible that a smaller county existed in one of those two states. No joy – Arthur was smaller than any of those 159.

I confidently went out into the world thinking Arthur County, ND was the smallest county in the United States.

But then it dawned on me that Texas had 254 counties. In those days it wasn’t the population behemoth that it is today, and with only 269,000 square miles, a lot of those counties had to be pretty small.

And so I found it – Loving County – population 67. That’s its population today; I can’t recall the number from the 1950 census (which would have been the number I found), but I think it was very close to that. And Loving County really is the smallest county (by population) in the United States even now.

So am I telling you anything you didn’t already know? Probably not – I’m guessing most readers of this blog have long since learned this little bit of trivia. And you learned it from Wikipedia, here. You will also discover that Arthur County is only fifth on the list, bigger than three counties in Texas.

Wikipedia makes it just much too easy! Imagine, if you will, that I’d had Wikipedia as a child. Think of all the articles I could write for this blog containing utterly useless information about everything. No more cleverness or labor required – all data is right there at your fingertips.

Now maybe I can play one-up-man-ship with Wikipedia? Through careful study of the RMRA, I discovered three states that have exclaves: New York, Kentucky and Hawaii.

* Liberty Island and the parts of Ellis Island that belong to New York are surrounded by New Jersey. These are also exclaves of New York County (Manhattan).

* The westernmost part of Kentucky (part of Fulton County) cannot be reached without crossing Missouri or Tennessee.

* Oahu and Kauai are separated by more than 24 miles, which means that one has to cross international waters to get from one to the other. (But since they are different counties, neither Honolulu nor Kauai counties have exclaves.)I also note that Brookline, MA is in Norfolk County, separated from the rest of the county by Middlesex and Somerset counties.

So there, Wikipedia! Oh – alright – not so fast. See here. I haven’t had the courage to go through it all and see what I’m missing. Why bother?

There are some questions for which the RMRA is not especially useful. For example, what are the largest and smallest counties by land area? Excluding Alaska (and by all means, let’s exclude Alaska), then simply by inspection any kid will tell you that San Bernardino, CA, is the biggest county in the country. At 20,000 square miles, it is almost as big as West Virginia.

What is the smallest county? Before resorting to Wikipedia, I spent a sleepless night pondering this problem. I thought Hawaii’s Kalawao County might fit the bill. Boy was I wrong!

Kalawao County is what’s left over from Father Damien’s leper colony on the north coast of Molokai. At midnight, I thought it was just the famous little peninsula that juts offshore. However my American Road Atlas (published by Langenscheidt, and nicer but considerably pricier than the RMRA) shows the county is considerably bigger than that – by about 2 or 3 times.

And what about RMRA? Shockingly, it doesn’t show Kalawao County at all, neither on the map nor in the index! I don’t think it ever has. I find this bothersome.

Nevertheless, neither atlas cites areas of any county, so it really is necessary to turn to Wikipedia. Wonderfully enough, Wikipedia does not have a list of the smallest counties by area – they only list the smallest county in each state – and then you have to look at a state list. Now there’s a good job here for some kid!

The matter is complicated because Virginia has a series of independent cities – the smallest of which is Falls Church. At 2.2 square miles, this is the smallest county-like subdivision in the US. But it isn’t a county. The smallest actual county is Arlington County, VA, at 26 square miles (compared to Kalawao’s 52).

Now what subtle distinction in local governance disqualifies Falls Church, and grants Arlington the status of smallest county? I have no idea.

A county that I’ve never heard of – Colorado’s Broomfield County – has only 28 square miles. It surrounds a suburb of Denver by the same name – how it got to be its own county I have no idea. And Bristol County, RI, clocks in at 45.

But this is not the worst. I can surely be forgiven for overlooking city-states in Virginia or anomalies in Colorado. What is harder to understand is how I missed Manhattan! New York County (which includes Manhattan, some smaller islands, and Marble Hill) comes in at 34 square miles. This, surely, would have been a better midnight guess for the smallest county in the country.

Wikipedia makes me feel old, rendering the skills of a lifetime obsolete. Just the other week my daughter suggested I needed to buy a GPS.

Never!

Daniel Jelski is Dean of Science & Engineering State University of New York at New Paltz.

-

China’s Heartland Capital: Chengdu, Sichuan

On May 12, 2008, Chinese architect Stepp Lin was focusing intensely on his professional licensing exam in a testing center in central Chengdu when suddenly he felt someone bumping his desk. By the time he looked up to see what it was, most of the other exam takers were frantically fleeing for the exit. It turns out that what he was feeling were the tremors of what was to be the most devastating earthquake to hit China in recent memory.

China’s heartland province of Sichuan was overtaken by an 8.0 earthquake that rocked the region that day. The quake was so powerful that it was felt as far away as Beijing. Graphic images broadcast around the world showed the devastation caused by the powerful tremor. All in all, it is estimated that more than 60,000 people perished in the Sichuan earthquake.

During the aftermath, the response from both within China and abroad in terms of aid was highly encouraging. Unfortunately, the footage of primary schools reduced to rubble resulting in the deaths of thousands of children and the subsequent scandals regarding culpability denial and cover-up did not bode well for China’s new image.

Surprisingly, Sichuan’s capital and largest city, Chengdu, escaped from the earthquake largely unscathed. Most of the serious damage took place in rural areas where buildings, due to lack of sufficient funding and regulation, had not been constructed to safety standards. Building safety codes have since been updated and are now rigorously enforced.

Perhaps more importantly, the 2008 Sichuan earthquake managed to highlight the growing disparity between the rich and poor, urban and rural areas of China.

Unlike the United States, where suburbanization has managed to blur the line between rural and urban, the contrast remains stark in the Middle Kingdom.It is no secret that within the framework of rapid development, China is urbanizing at unprecedented rates. Beijing and Shanghai continue to lead the country politically and economically, but a group of ‘second tier’ cities is now being targeted by China’s planners for increased new investment. Included in this group are up-and-coming cities like Nanjing, Dalian, Tianjin and Chongqing.

Yet perhaps no other second tier city represents the future of China more than Chengdu (pronounced chung-doo). Strategically located at the geographic heart of China, Chengdu bridges the gap between the country’s booming eastern seaboard and the still largely mysterious far west.

Chengdu is one of China’s oldest cities, with continuous settlement dating back to the ancient Kingdom of Shu. Today, the city is renowned for its local spicy cuisine and famous Panda Breeding Center. It is also a popular launching-off point for international trekkers heading onto Tibet. Within China, Chengdu is reputed for its leisurely atmosphere where friendly locals often take off work early to sip tea and relax over a game of mahjong.

Sitting at an elevation of about 1,600 feet on the western portion of the Sichuan Basin, Chengdu’s climate is mildly humid-neither too hot in the summer nor too cold in the winter. Yet one drawback is the presence of the pervasive fog that hovers low in the sky year-round, making Chengdu one of least-sunny cities in China.

Similar to Beijing, Chengdu is concentrically organized with ring roads circling the city. At the center of the city is Tianfu Square-a pleasant public space featuring larger-than-life water fountains and a large statue of Chairman Mao. Nearby is the Jin River, which flows through the middle of the city, dividing it in half.

Despite the slower pace of life, at least in comparison with the rest of China’s hyper urbanity, the Central Government has recognized the city’s advantages. Being the western-most big city in China, Chengdu is China’s gateway to central Asia. As such, the city has been identified as an air traffic hub. Already, Chengdu International airport is one of the busiest in the mainland. Next year, Air China inaugurates its new Chengdu-Los Angeles route: the first direct flight from the city to the United States.

The new Air China route to LA reflects the growing presence of U.S. firms in the area. Technology companies like Microsoft and Intel have realized the competitive advantages of opening research and development facilities in an area of the country where the cost of doing business is still relatively low. These firms have located their offices in an area in the south of Chengdu that has been designated as the ‘Hi-Tech Zone’ by China’s Ministry of Science and Technology.

Along with becoming western China’s high tech center, the city is grabbing a foothold on the country’s aviation industry. Chengdu Aircraft Industrial Group (CAC), which was contracted out by Dallas-based Vought Aircraft, supplied the rudder for Boeing’s new 787 ‘Dreamliner’ jet. CAC also supplies parts for Boeing’s 757 series.

To accommodate the new business, the city is going through a construction boom. Although Chengdu had a late start on its eastern counterparts, the city is attracting high-profile developers like New York-based Tishman Speyer and Singapore’s CapitaLand – both of whom currently have large-scale commercial and retail projects being built in the city. Chengdu has even recruited Hong Kong businessman Allan Zeman to develop a version of Hong Kong’s popular nightlife district, Lan Kwai Fong, scheduled to open in March.

The city’s development would not be complete without an overhaul of its transportation system. One word summarizes the current state of Chengdu’s roads: chaos. The traffic on the streets remains an assortment of bicycles, motorbikes, automobiles and buses. Yet, as incomes rise and more people purchase cars, the congestion on the streets is becoming unbearable. Furthermore, the fact that the streets do not follow a formal grid pattern, but rather array out from the center of the city, adds another degree of complexity to Chengdu’s traffic dilemma.

Thankfully, the city’s first subway line is slated to open in 2010. As additional underground lines become operable, it will also give the city a better sense of cohesiveness as the limited number of surface level crossings of the Jin River currently contributes to both a physical and psychological divisiveness.

In discussing the rise of Chengdu as a hotbed of economic activity, it is worth mentioning the city’s relationship with its closest rival, Chongqing. Chongqing, which was separated from Sichuan Province in 1997 to become an autonomous provincial-level municipality, lies just over 200 miles to the east. The city has the advantage of direct access to the Yangtze River, providing a strategic connection to the river’s terminus of Shanghai.

Chongqing’s urban development is limited by the surrounding mountainous terrain-thus the reason for the dense high-rise jungle rising in the skyline. Chengdu, in contrast, has an abundance of land for growth and is more likely to sustain long-term development. Also, the fact that Chongqing has been plagued by corruption and local mafia activity in recent years means that foreign firms may be more attracted to safer Chengdu.

That is not to say that there is not room for both cities in China’s future. In fact, the two cities are likely to form what will become the Chengdu-Chongqing mega-region – the economic powerhouse of western China. Already, other mega-regions in China like the Bohai Bay Rim (Beijing, Tianjin and Dalian), the Yangtze River Delta (Shanghai, Hangzhou, Nanjing and Suzhou) and the Pearl River Delta (Guangzhou, Dongguan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong) are setting groundbreaking standards in the history of global urbanization.

The Sichuan earthquake of 2008 managed to bring about an awareness of the major issues still facing China. In stark contrast to the days of the Cultural Revolution when urban areas were viewed as pariahs, the Sichuan quake solidified the triumph of the city over the countryside. As the city on the frontier, Chengdu is likely to become a key player as thousands of migrants arrive from Sichuan and adjacent provinces. How these newcomers are incorporated represents a great challenge for China as it shifts from a largely rural to a predominately urban country.

Adam Nathaniel Mayer is a native of California. Raised in Silicon Valley, he developed a keen interest in the importance of place within the framework of a highly globalized economy. Adam attended the University of Southern California in Los Angeles where he earned a Bachelor of Architecture degree. He currently lives in China where he works in the architecture profession.

-

Reducing Traffic Congestion and Improving Travel Options in Los Angeles

While traffic congestion plagues many cities, Los Angeles stands apart. The Texas Transportation Institute tracks congestion statistics for U.S. metropolitan areas on an annual basis, and Los Angeles routinely ranks first for both total and per-capita congestion delays. Considering the value of wasted time and fuel, TTI estimates the annual cost of traffic congestion in greater Los Angeles at close to $10 billion.

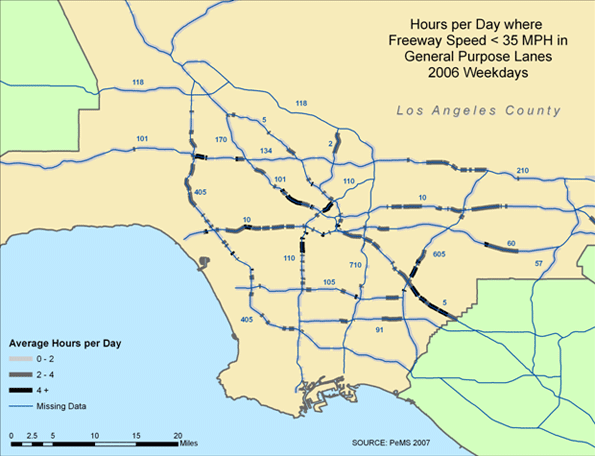

The map in Figure 1, based on 2006 Caltrans sensor data, illustrates the weekday pattern of traffic congestion on the LA freeway network. Congestion is pervasive throughout much of the county; most freeways have segments on which traffic averages less than 35 mph at least two hours per day, and many bottlenecks are congested at least four hours per day.

Figure 1. Traffic Conditions on the LA Freeway Network

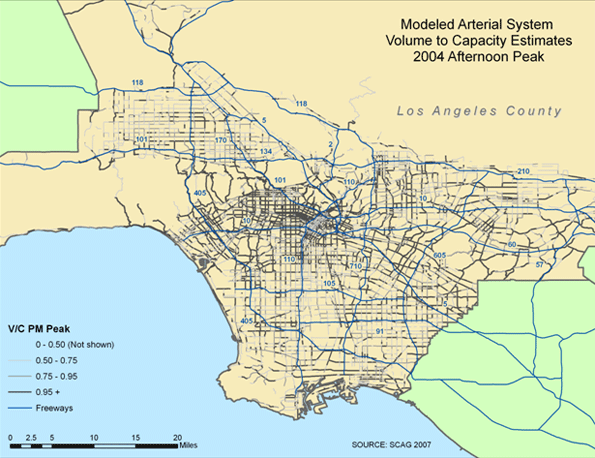

Conditions on the surface streets are not much better. The map in Figure 2, based on 2004 volume-to-capacity (V/C) estimates from SCAG, depicts the pattern of afternoon traffic congestion on the county’s largest arterials. Here again it is evident that traffic congestion is broadly dispersed, yet the pattern is particularly intense between downtown Los Angeles and the Westside.

Figure 2. Traffic Conditions on LA Surface Streets

With the recent run-up in fuel prices followed by a severe recession, total travel in Los Angeles has declined over the past two years, and congestion has correspondingly eased. Yet if past trends hold, this reprieve is likely to be fleeting. Should the region’s economy and population grow in the coming decades, as some forecasts predict, the probable outcome is even more vehicle travel and in turn more intense congestion.

Controversial Solutions for a Daunting Problem

Researchers at the RAND Corporation were asked to recommend strategies capable of reducing LA traffic within five years or less (the short timeframe rules out land-use reforms along with major infrastructure investments). The resulting report, Moving Los Angeles: Short-Term Policy Options for Improving Transportation, offers recommendations at once controversial and likely inescapable. To achieve lasting traffic relief, it will be necessary to manage the demand for travel through pricing reforms (e.g., congestion tolls) that increase the cost of driving and parking in the busiest corridors and areas during peak travel hours. Other measures—better transit service, ridesharing programs, traffic signal synchronization, and the like—can complement pricing, but are not on their own sufficient to stem current and projected future traffic congestion.Few Strategies Offer Much Promise

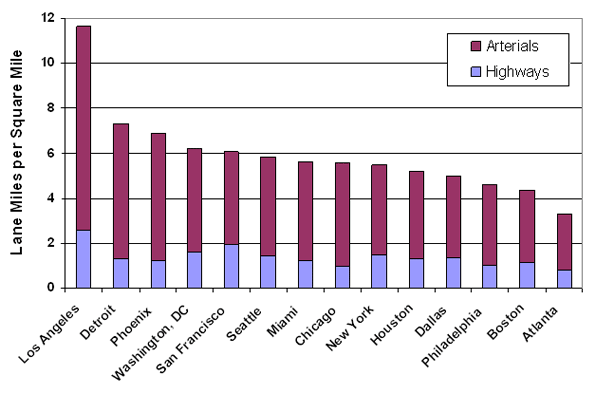

Just why should this be so? Consider, first, that traffic congestion results from an imbalance between the supply of roads and peak-hour automotive travel. In fact, congestion can be viewed as a solution (though an unpleasant one) to this imbalance; when demand exceeds supply, congestion makes us wait our turn for available road space to balance the equation. Over the past several decades, the gap between supply and demand has widened considerably; population growth, economic expansion, and rising incomes have fueled the demand for more vehicle travel, while road construction has stagnated. We have therefore been relying, more and more, on congestion to resolve this imbalance.One response would be to build or expand more roads to accommodate additional vehicle travel. Setting aside policy concerns related to greenhouse gas emissions and energy security, the prospects for “building our way out of congestion” are limited. To begin with, there simply isn’t much space to build new roads in Los Angeles, particularly in the most densely developed urban areas. As shown in Figure 3, the density of the road network in the greater Los Angeles region, measured in lane miles per square mile, is already far greater than in any other large metropolitan area in the country.

Figure 3. Road Network Density in Major Metropolitan Areas

We also lack the resources to engage in an extensive road building spree. In recent decades, federal and state elected officials have failed to increase fuel taxes enough to offset the effects of inflation and improved fuel economy, thus hobbling the major source of funding for road construction and repairs.

Even if we could expand the road network, though, the benefits would be limited by a phenomenon described as “triple convergence.” Congestion has been a problem for years, and many individuals deliberately alter their travel patterns to avoid severe traffic. When an investment in road capacity reduces peak-hour congestion, many will conclude that they no longer need to go out of their way to avoid congestion delays and will thus “converge” on the improvement from (a) other times, (b) other routes, or (c) other modes of travel. The net effect is that the initial traffic-reduction benefits will usually not last over time. This is why we often see, for instance, that the improved traffic flow resulting from a new freeway lane does not last for more than a couple of years.

If supply-side remedies do not create sustainable reductions in traffic, it becomes necessary to examine ways of reducing peak-hour travel demand. Commonly employed options include improved transit service, voluntary ridesharing programs, flexible work hours, and telecommuting. Unfortunately, the congestion-reduction benefits of these strategies are likewise undermined by triple convergence. If a new subway line induces some peak-hour drivers to switch to transit, other drivers will soon converge on more freely flowing roads to take their place. Indeed, the effects of triple convergence explain why traffic congestion has grown steadily worse despite considerable state and local investment in a broad range of congestion-reduction strategies.

Only Pricing Strategies Promise Sustainable Reductions in Traffic Congestion

This brings us to the rationale for pricing strategies. Among the many possible options for reducing traffic congestion, only pricing resist the effects of triple convergence. By increasing the cost of driving or parking in the busiest areas or corridors during the busiest times of day, pricing measures manage the demand for peak-hour travel, in turn reducing congestion. Once traffic flow improves, the prices remain in place, thus deterring excessive convergence on the newly freed capacity.Pricing strategies offer two additional benefits. First, pricing generates revenue to support needed transportation investments. And in comparison to sales taxes, a common option for raising local transportation revenue, pricing has been shown to reduce the relative tax burden on lower income groups (though wealthier individuals consume more taxable goods than their less-affluent counterparts, to an even greater extent they (a) drive more, (b) are more likely to travel during peak hours, and (c) are more likely to pay peak-hour tolls rather than alter their travel choices). Second, pricing enables more efficient use of the road capacity that we already have, because roads on which traffic flows smoothly (at roughly 40 mph or higher) can carry far more vehicles per lane per hour than roads snarled in stop-and-go congestion. Paradoxically, then, we see that the introduction of pricing enables roads to accommodate more peak-hour trips. It is therefore useful to think of pricing as a means of managing peak-hour travel demand rather than reducing it.

Pricing Strategies Will Be Particularly Valuable in Los Angeles

Pricing holds promise for most major cities, but the case in Los Angeles is especially compelling. To understand why, it is necessary to consider the interactions between population density and travel behavior, factors that help to explain the severity of LA traffic.Contrary to its reputation for sprawl, Los Angeles is quite densely populated when viewed at the regional scale. Downtown Los Angeles isn’t as dense as, say, Manhattan or central Chicago, but the suburbs surrounding Los Angeles are much denser than the typical suburb, leading to high aggregate density on a regional basis.

As population density increases, individuals tend to drive less on a per-capita basis. Trip origins and destinations are closer together, leading to shorter car trips, and in dense neighborhoods people can rely on alternatives such as walking, biking, or transit for a larger share of trips. Yet this can be overwhelmed by the fact that there are also more drivers competing for the same road space within a given area, thus intensifying traffic congestion. The net effect is that greater population density tends to exacerbate congestion—think downtown Manhattan.

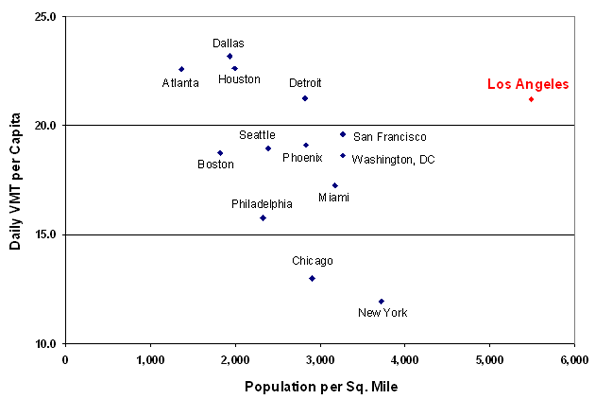

LA traffic congestion is further exacerbated by the fact that Angelinos do not curtail their driving as much as one would expect in response to higher population density. Figure 4 compares per-capita vehicle miles of travel (VMT) and population density for the 14 largest metropolitan regions in the country.

Figure 4. Population Density vs. Per-Capita VMT for the 14 Largest U.S. Metropolitan Regions

Looking across the different regions, there is a fairly consistent relationship in which per-capita VMT declines with regional density. Los Angeles, though, bucks this trend. The only other metropolitan regions with higher per-capita VMT (Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Detroit) are all much less dense than Los Angeles. For regions in which the level of density approaches that of Los Angeles (San Francisco, Washington D.C., and New York), per-capita VMT is much lower.

In short, we see a confluence of three density-related factors that combine to explain the severity of congestion in Los Angeles: (1) congestion is likely to rise with increased population density; (2) Los Angeles is much denser than its peers at the regional level; and (3) Los Angeles exhibits a surprisingly high level of per-capita VMT relative to its density. The third of these underscores the importance of pricing strategies as a means of managing the demand for automotive travel in Los Angeles.

In the end only pricing strategies promise sustainable reductions in traffic congestion. Other measures – including improvements in alternative transportation modes – can be beneficial, but none will be nearly as effective as pricing. This recommendation will no doubt stir controversy, but pricing offers the only realistic prospects for managing peak-hour travel demand in the most traffic-choked of American metropolises.

Dr. Paul Sorensen is an operations researcher at the RAND Corporation, wherehe serves as Associate Director of the Transportation, Space, and Technology program. Dr. Sorensen has published peer-reviewed studies in the areas of geographic information analysis, location optimization modeling, emergency response logistics, and transportation finance policy, and he also holds aU.S. patent on a methodology for forecasting the demand for ambulance services. Dr. Sorensen received a BA in computer science from Dartmouth College, an MA in urban planning from UCLA, and a PhD in geography from UCSB.