Kotkin is a very rare thing: a principled moderate. He went Obami in the last election. He’s over that now.

Blog

-

The Limits Of Politics

Reversing the general course of history, economics or demography is never easy, despite even the most dogged efforts of the best-connected political operatives working today.

Since the 2006 elections – and even more so after 2008 – blue-state politicians have enjoyed a monopoly of power unprecedented in recent history. Hardcore blue staters control virtually every major Congressional committee, as well as the House Speakership and the White House. Yet they still have proved incapable of reversing the demographic and economic decline in the nation’s most “progressive” cities and states.

Obama and his congressional allies have worked overtime in favor of urban blue-state constituencies in everything from transportation funding and energy policies to the Wall Street bailouts and massive transfers of private wealth to powerful public-employee unions. Yet these areas continue suffering from net outmigration and stubbornly high job losses – as well as from some of the most severe fiscal imbalances in the nation.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the president’s hometown of Chicago. The Windy City has suffered a very bad recession and may have fallen to its worst relative position since the Daley reconquista in 1989. As Chicago blogger Steve Bartin points out, even the presence of a Daley operative in the White House has failed to prevent the city from falling “in a funk.” He writes that even a reliable booster, columnist Mary Schmich of the Chicago Tribune, has lately described the city “as edgy, a little sullen and scared, verging on depressed.”

There’s plenty reason for feeling low, well beyond the humiliating loss of the Obama-backed Olympics bid last year. For example, Oprah Winfrey, the city’s one bona fide A-list celebrity, is retiring her talk show in 2011. She is also reportedly shifting much of her media empire to Southern California, which, for all its admitted problems, has gads of celebrities and much better weather.

Chicago’s most serious concern, however, revolves around the economy. In June, its unemployment rate peaked at 11.3%, far outpacing the national unemployment rate of 10%. Since 2007, the region has lost more jobs than Detroit, and more than twice as many as New York. Chicago’s total loss over the entire decade is greater than any region outside Detroit: about 250,000 positions, which is about the amount its emerging mid-American rival Houston has gained. In hard times businesses tend to look for places with a friendly environment for their enterprise. They avoid high taxes, political payoffs and inflated public employee salaries – all well-known Chicago specialties. These costs are undermining the city’s competitive position in, for example, the convention business, among others.

Other key sectors are also flailing. Political influence in Washington will not stem the flow of high-wage trading jobs away from the Mercantile Exchange to decentralized electronic exchanges. Nor can it reverse the deteriorating state fiscal crisis caused by weak economies and exacerbated by insanely high pensions and out of control spending policies. Late last month

Moody’s and S&P downgraded the debt ranking for the State of Illinois. Of course, such fiscal malaise is not limited to Chicago or Illinois. True blue California has an even worse debt rating. New York, another blue bastion, is also just about out of cash.To be sure, the recession has not hurt New York as much as Chicago, but the Big Apple has lost heavily , including 50,000 financial sector jobs since 2007. The outrageous bonuses to a few well-placed financial types will cushion but not deflect the influence of declining high-wage jobs. This can be seen in the striking weakness in the once seemingly unstoppable high-end condominium market. Particularly hard hit have been recent gentrified neighborhoods like Williamsburg in Brooklyn, N.Y., much like the hard-hit, newly developed areas along the Chicago lakefront.

Other blue bastions have been shedding jobs as well, both during the recession and over the whole decade. Beyond Chicago and Detroit, the biggest losses among the mega-regions have taken place in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles-Long Beach and Boston. Big money can still be made in Silicon Valley, Hollywood or around the academic economy of Boston, but in terms of overall jobs, the past decade has been dismal for these regions. Meanwhile, the consistent big gainers have been – besides Houston – Dallas and Washington, D.C., the one place money really does seem to grow on trees. Even Miami, Phoenix and San Bernardino-Riverside, in California, boast more jobs today than in 2000, despite significant setbacks in the recent recession.

These trends coincide with continuing shifts in demographics. The recession may have slowed the pace of net migration, but the essential pattern has remained in place. People continue to leave places like New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles for more affordable, economically viable regions like Houston, Dallas, Austin and San Antonio. Overall, the big winners in net migration have been predominately conservative states like Texas – with over 800,000 net new migrants – notes demographer Wendell Cox. In what Cox calls “the decade of the South,” 90% of all net migration went to southern states.

Utah, Colorado and the Pacific Northwest have also experienced positive flows – but perhaps most striking have been the migration gains, albeit modest, in Great Plains states such as Oklahoma and South Dakota as well as Appalachian Kentucky and West Virginia. Historically these places shipped many of their people to cities of the industrial Midwest, the eastern seaboard and California; that is no longer the case.

Ultimately these shifts could undermine the true blue political strategy, perhaps as early as the 2010 congressional and state elections, and certainly after reapportionment. By 2012, the census will likely take seats from New York, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Ohio, handing them over to Texas, North Carolina, Georgia and Utah. Perhaps nothing will epitomize the new reality more than the fact that California, now among the most extreme blue states in terms of governance, will not gain a Congressional seat for the first time since the 1860s.

These trends suggest that the current administration and the majority party in Congress must adjust their strategy. Further attempts to push a radical “progressive” agenda – expansive public employee bailouts, higher taxes and radical measures to combat “climate change” and suburban development – might please their current core constituencies, but they have the perverse effect of driving even more people and jobs out of these regions.

All these underlying trends appear a boon to Republicans. But Democrats could counter the emerging GOP edge by appealing to the needs of these ascendant regions. By their very nature, growth states have the most urgent need for government investments in basic infrastructure, something traditional Democrats long have espoused. Moreover, such areas tend to become more tolerant as they welcome outsiders, and could be turned off to excessive Republican social conservatism.

For any of this to work, however, Democrats must first abandon their current narrow, urban-centric blue-state strategy. They must learn to adjust their appeal to regions on the upswing, or things could turn out very badly for them very soon.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History

. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.

-

Avoiding Housing Bubbles: Regulating the (Land Use) Regulators

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernacke called for stronger regulation to avoid future asset bubbles, such as the housing bubble that precipitated the international financial crisis (the Great Recession) in an Atlanta speech.

The Chairman appears to miss the fact that regulation itself was a principal cause of the Great Recession. The culprit, however, was not financial regulation, but rather land use regulation, which drove house prices so high in highly regulated markets. When households that could not afford their mortgages defaulted, the losses were far too intense for the mortgage industry to sustain, and thus the Great Recession.

This is not to ignore the role of Congress and others, which fueled more liberal mortgage credit, and created the excess and credit-unworthy

additional demand for home ownership.This higher demand, however, was only a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for creating the bubble, which when burst, precipitated the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. In many markets, there was relatively little increase in house prices relative to incomes, as prices remained at or below the historic Median Multiple (median house price divided by median household income) standard of 3.0. In other markets, however, prices reached from 5 to 11 times incomes.

Already, a new bubble may be on the way to developing. Even after the huge losses, house prices in California were only beginning to return to sustainable historic levels (3.0 Median Multiple). Since bottoming out, however, prices in California have risen 20%, at an annualized rate greater than that of any bubble year.

Perhaps the first principle of regulation is understanding what to regulate. In the case of the housing bubble, it was land use regulations themselves that needed to be regulated.

To avoid future housing bubbles, no more effective action could be taken than to repeal the restrictive land use regulations, without which the last bubble would have been, at most, only slight compared to the destructive reality that ensued. -

Urbanity Drives Gay Rights Victory in Washington

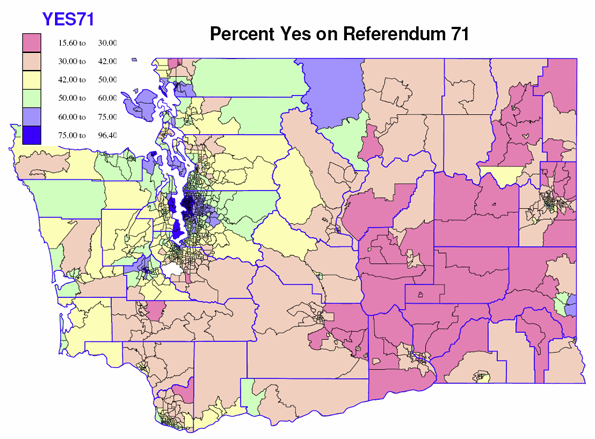

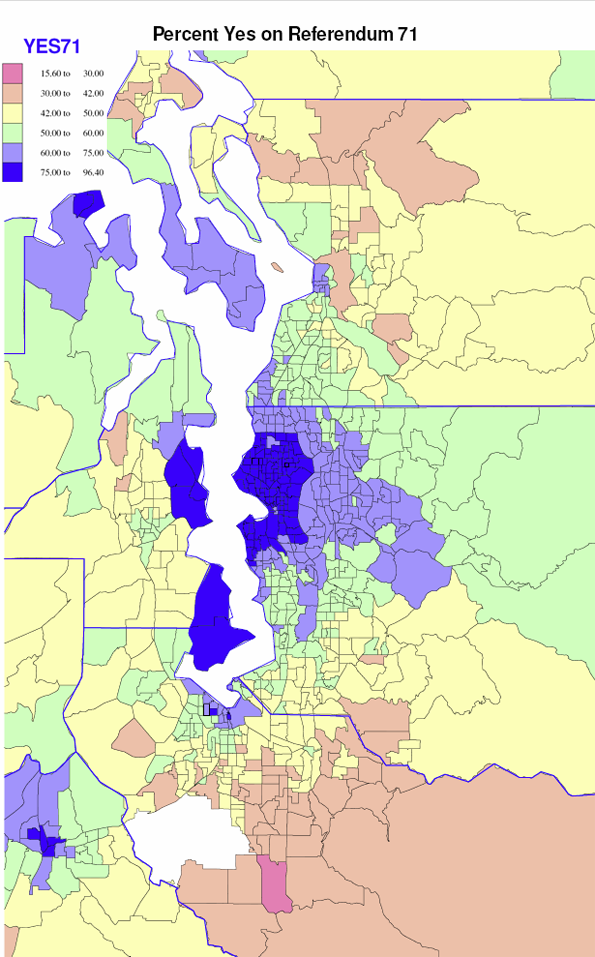

If anyone were to doubt that there really are two Washingtons, that the Seattle metropolitan core (and its playgrounds) are another world from most rural to small city Washington (especially east of the Cascade crest), a look at the maps for the vote on Referendum 71 last November should be persuasive. These are not subtle, marginal differences, but indisputable polarization in what political and cultural researchers may call the modernist-traditional divide.

Referendum 71 passed by a 53 to 47 percent vote, and revealing the power of the King County electorate, which alone provided a margin of 204,000, compared to a statewide margin of 113,000! To overcome the problem of variable size of precincts, and the need to suppress too small numbers, I aggregated precincts to census tracts, which have the added advantage of permitting comparison of electoral results with social and economic data from the census.

Looking at the statewide map, about 85 percent of the territory of the state (95 % in Eastern WA, 70 % in western WA) voted NO. But the strong no vote came from overwhelmingly rural areas and small towns. The only core metropolitan census tracts that voted a majority no were in Richland-Kennewick area, Yakima and Longview. The heart of traditionalist, and arguably, of anti-gay sentiment lies in the farm country of eastern Washington, especially wheat and ranching areas in Adams, Douglas, Garfield, Lincoln, Walla Walla and Whitman counties, but extending also to the rich irrigated farmlands of Grant, Franklin, Benton and Yakima counties. The highest no votes in western Washington were far rural stretches, and most interesting, Lynden, home to many Dutch descendants, members of the conservative Christian Reformed Church. Not surprisingly the census tracts in eastern Washington which supported Referendum 71 were the tracts dominated by Washington State University in Pullman, around Central Washington university in Ellensburg, the mountain resorts tracts in western Okanogan (Mazama, Twisp), and a few tracts in the core of the city of Spokane.

Across western Washington majorities against Ref 71 prevailed over a sizeable contiguous southeastern area, from northern Clark and Skamania through urban as well as rural Lewis county (reinforcing the county’s reputation of being the anti-Seattle!) into much of southeastern Pierce county. A lesser vote against 71 occurred in the rest of rural small town western Washington, including most of rural Snohomish county.

The zone of strong support, voting over 60 percent in favor, flowed largely from Seattle and its inner commuting zone, its spillover playgrounds and retirement areas of Port Townsend and the San Juans, and college and university dominated tracts around Western Washington in Bellingham, the Evergreen State College, Olympia, plus the downtown cores of Vancouver, Tacoma and Everett. Weaker but still supportive were rural spillover, retirement and resort tracts, often in coastal or mountain areas of Pacific, Grays Harbor, Jefferson, Clallam, Skagit and Whatcom counties.

Looking at the detailed map of central Puget Sound, we can see revealing contrasts between the two camps. Support levels of over 75 percent almost coincides with the city of Seattle boundaries (not quite so high in the far south end), and its professional commuting outliers of Bainbridge and Vashon, plus the downtown government core of Olympia and tracts around the University of Puget Sound and the UW Tacoma.

Moderately high support (60 to 75 percent) surrounds the core area of highest support, most dominantly in the more affluent and professional areas north of Seattle through Edmonds and east to Redmond, Issaquah and Sammamish (Microsoft land). Weak but still positive votes occurred in the next tier of tracts, around Olympia, north and west of inner Tacoma, most of urban southwest Snohomish county and much of exurban and rural King county (quite unlike most rural areas). But on the contrary, the shift to opposition is remarkably quick and strong in southeastern King and especially in Pierce county, in northern and eastern Snohomish county, and, not surprisingly, in military dominated parts of Kitsap county (e.g., Bangor) and Pierce (Fort Lewis).

The temptation to compare the voting levels of census tracts with social and economic conditions of those tracts is too great to resist. Here are the strongest correlations (statewide).

Washington State Correlations with voting in favor of Ref 71 % Use transit 0.75 % Drive SOV -0.54 % Non-family HH 0.65 % HW families -0.45 % Single 0.48 Average HH size -0.53 % Same sex HH 0.57 % aged 20—39 0.43 % under 20 -0.55 % foreign born 0.28 % Born in Wash. -0.4 % College grad 0.65 % HS only -0.62 % Black 0.27 % white -0.13 % Asian 0.42 % Hispanic -0.22 Manager-Profess 0.53 % Craft occup -0.46 % in FIRE 0.34 % laboring occup -0.47 These statistics reflect the profound Red-Blue division of the American electorate, in both the geographic differences (large metropolitan versus rural and small town), as well as the modern versus traditional dimension (socially liberal or conservative). The strongest single variable is not behavioral, but transit use is a surrogate for the metropolitan/non-metropolitan split. The critical social characteristic lies in the nature of households: the traditional family versus non-families (partners, roommates, singles). This is a powerful tendency, and useful to describe differences in areas, but of course many in families – often more educated and professional – support Ref 71, and many singles – often elderly, or opposite sex partners – opposed it, especially in more conservative parts of the state.

The next strongest set of variables, clearly visual from the maps, lay in the strong split of the electorate according to the predominant educational level of the tracts. The tendency of the more educated to support 71 represents the key statistic of the “modern” vs “Traditional” dimension, and is closely related to the differences by occupation and industry. Managers and professionals, and those working in finance, and information sectors tended to be supportive of 71, while those in laboring and craft occupations, and in manufacturing, transport and utilities, tended to oppose. (South King county and much of Pierce county have high shares of blue collar jobs).

Finally differences by race exist, but are not so strong as, say, in the presidential election in 2008 (although the correlation of the percent for Ref 71 and for Obama was .90).

Yes, greater Seattle is indeed very different than the rest of Washington and much of America as well.

Richard Morrill is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Washington. His research interests include: political geography (voting behavior, redistricting, local governance), population/demography/settlement/migration, urban geography and planning, urban transportation (i.e., old fashioned generalist).

-

Why New York City Needs a New Economic Strategy

When Michael Bloomberg stood on the steps of City Hall last week to be sworn in for a third term as New York City’s mayor, he spoke in upbeat terms about the challenges ahead. The situation, however, is far more difficult than he portrays it. American financial power has shifted from New York to Washington, while global clout moves toward Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. Even if the local economy rebounds, the traditional media industries that employ many of Bloomberg’s influential constituents likely will continue to decline. New Yorkers have long had an outsize view of their city; historically, its mayors have touted mottos that encouraged that view, from Rudy Giuliani’s “capital of the world” to Mike Bloomberg’s “luxury city.” But as Bloomberg begins his new term, New York needs to reexamine its core economic strategy.

A good first step would be to recognize that the world owes New York nothing. The city cannot simply rely on inertia and the disbursements of Wall Street megabonuses to save its economy. Instead, it needs to rebuild its middle-class neighborhoods and diversify toward a wide range of industries that can capitalize on the city’s unique advantages—including its appeal to immigrants; the port; and its leadership in design, culture, and high-end professional services.

It’s also time to get rid of the Sex and the City image and start making New York a city where people can have both sex and children. This will become more important as the millennial generation enters its late 20s and early 30s later this decade. This is when many young migrants to the city, including upwardly mobile immigrants, typically become ex–New Yorkers.

Despite all the “back to the city” hype, New York over the past decade suffered one of the highest rates of out-migration of any region in the country. Young singles may come to New York, but many leave as they get older and have families. An analysis by the city controller’s office in 2005 found that people leaving the city were three times more likely to have children than those arriving.

If New York is to thrive, it will need to keep more of these largely middle-class families. To do that, it needs to diversify its economy beyond Wall Street, which in 2007 provided roughly 35 percent of all income earned in the city. Since the recession, the city has lost 40,000 financial-service jobs, but the industry has been quietly downsizing for years: over the past two decades, more than 100,000 financial-services jobs have disappeared from New York. In good years, financial services provided an enormous cash engine, but it can no longer provide enough jobs. According to an analysis by the Praxis Strategy Group, finance now accounts for barely one in eight jobs in New York City. Most job growth has come instead in lower-paying professions like health care and tourism.

To become economically sustainable, New York needs to create policies that help encourage development in areas where its less wealthy citizens live. Most outsiders identify New York almost exclusively with Manhattan, yet roughly three out of four New Yorkers actually live in the outer boroughs: Queens, Brooklyn, Staten Island, and the Bronx. Neighborhoods like Bay Ridge, Whitestone, Flatbush, Howard Beach, and Middle Village are really New York’s middle-class bastions.

Over the past decade, these communities have provided a critical middle ground between the bifurcated Bloombergian “luxury city” with its high-end enclaves and the many distressed neighborhoods throughout the city. Although the mayor, some urbanists, and many developers would like to make these middle-class enclaves ever denser, their very appeal often lies in their moderate scale, proximity to work areas, decent schools, and parks. Those attributes hold sway, even in a recession. “Brand- new and expensive places have not held up as well as the established family neighborhoods,” says Jonathan Bowles, director of the New York–based Center for an Urban Future.

Nurturing these neighborhoods will require a distinct shift in public policy. During the Bloomberg years the big subsidies have gone to luxury condo megadevelopments, sports stadiums, or huge office complexes. Consider the 22-acre Atlantic Yards project in downtown Brooklyn, which will include luxury housing and a new arena for the NBA’s Nets; one recent report by the city’s Independent Budget Office put the total subsidies provided by the city, New York state, and the transit authority at $726 million and estimated the project will hurt, not help, the city’s economy over time.

More than anything, the plain-vanilla neighborhoods that represent New York’s real future will require policies that create a broad array of economic opportunities. Right now New York is so overregulated and highly taxed that only the most high-end business, such as big media and financial firms, can possibly thrive. The city has neglected its smaller firms, typically engaged in such activities as food processing, furniture making, and garment production. Traditionally these industries were run by Russian, German, Polish, and Italian immigrants; West Indians, Latinos, Koreans, Chinese, and South Asians do much of this work today. Over the past decade, the number of self-employed immigrants in New York has grown even as the number of self-employed among the native-born has dropped.

Earlier generations of urban residents as well as many immigrants today stay in the city to be close to their communities and industries dominated by them. These days many others stay in the city largely because of its cultural attributes and quality of life. This doesn’t mean these workers remain unreconstructed bohemians forever. Their priorities often change as they age, start businesses, and raise families. Different, more mundane issues—stable employment, taxes, safety, schools, and housing affordability—often determine whether they stay in the city. “It’s easy to name the things that attracted us—the neighbors, the moderate density,” says Nelson Ryland, a film editor with two children who works in his sprawling home in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood. “More than anything it’s the sense of the community. That’s the great thing that keeps people like us here.”

Technology will boost this sense of community. Online groups like the Flatbush Family Network can facilitate contact in different parts of a city among artists, families, and neighborhood groups, supplementing the traditional community adhesives of schools, churches, synagogues, and clubs. These new online institutions can perform some of the functions that urbanist Jane Jacobs’s “eyes on the street” did in the old, cohesive city neighborhood. Information about the arrival of a promising new store or restaurant, or the unwelcome appearance of a possible child molester, travels through these community networks much as it did when mothers spoke over the washing, men went to the pool hall, or kids hung out at the candy store.

Bloomberg has built on many of the achievements of his predecessor during his eight years in City Hall. This, combined with huge campaign spending from his personal fortune, is why voters sent him back for a third term. To position the city for prosperity in an economy that’s no longer overly dominated by Wall Street, he’d be wise to spend his final term focused on making new opportunities for people who live far from his own Upper East Side neighborhood—the people who represent the real future of New York.

This article originally appeared at Newsweek.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History

. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.

-

Obama’s Elite Power Base

Looking back at President Obama’s first year in office, this much is clear: Obama first enraged the right wing by seeming to veer far left, then turned off the left by seeming to abandon them. Even as Fox News fundamentalists rail against “socialism,” self-styled progressives like Naomi Klein scream about a “blown” opportunity to lead the nation from the swamp of darkest capitalism.

Both right- and left-wing critics fail to consider the fundamental nature of the Obama regime. This presidency represents not a traditional ideology but a new politics that mirrors the rise of a new, and potentially hegemonic class, one for which Obama is a near-perfect representative.

Every president and political movement, of course, brings to power an often-hoary group of grasping interest groups. Under the conservatives and George W. Bush, the favored classes included standbys like the fossil-fuel energy companies, Big Agriculture, suburban homebuilders, and the defense industry.

Rather than the “good old boys,” Obama’s core group hails from what may be best described as the “creative class” – the cognitive elite, or, to borrow from Daniel Bell’s The Coming of Postindustrial Society, the “hierophants of the new society.” They come not from traditional productive industry, but the self-conscious “knowledge” sectors – such as financial services, the software industry, and academia.

From early on, Barack Obama attracted big-money people like George Soros, Warren Buffett, and JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon far more effectively than his opponents in either party. As The New York Times’ Andrew Sorkin put it back in April, “Mr. Obama might be struggling with the blue-collar vote in Pennsylvania, but he has nailed the hedge-fund vote.”

Other bastions of support could be found in Silicon Valley, where Google Chairman Eric Schmidt and venture capitalist John Doerr were all early backers. Obama, the former law school professor, also did exceedingly well with academics, and many of his pivotal wins in the Midwest rested heavily on both votes and volunteers from college constituencies.

Finally Obama gained the early support of public-sector unions, now arguably the dominant power within the Democratic Party. Together, these groups now enjoy the lion’s share of influence inside the administration.

In contrast, the representatives of traditional Democratic sectors such as industrial labor unions, Latinos, or even many African Americans were slow to join the Obama bandwagon. Even after they joined his electoral coalition, they have received little in the way of succor from the president and the administration.

Indeed, for most of these voters, the past year has been an awful one. Unemployment for Latinos, blacks, and blue-collar workers has skyrocketed, particularly among males. For them, Obama’s economic plan has done very little – unsurprising given its primary focus on sustaining public-sector employment and large financial institutions.

In contrast, the core Obama constituencies appear to have ridden out the recession in fine shape. Mega-patron George Soros, for example, has boasted openly about how he was having “a very good crisis.” Much the same can be said of the largely pro-Obama hedge funds and investment bankers, for whom Paulson to Bernanke to Geithner has provided a double-play combination for the ages.

Academia has also emerged as a big winner. This administration is crammed with professors from Science Adviser John Holdren and Energy Secretary Steven Chu to former Harvard President Larry Summers, the director of the National Economic Council. More broadly, academics have reaped massive windfalls from the stimulus, both in terms of direct support for universities and funding for research projects.

One place where the priorities and class interests of the cognitive elite coalesce most has been on “climate change.” In contrast to manufacturers, farmers, or fossil-fuel firms, investment bankers, software companies, and university professors have little to fear from the rash of “green” policy initiatives.

In fact, for these groups, “climate change” often means a once-in-a-lifetime bonanza. Wall Street sees the administration’s “cap and trade” proposals as opening a whole new frontier to enjoy yet more profit. University researchers – particularly those with the right spin on the climate issue – have been big winners in the tens of billions of dollars being handed out by the Chu-led Energy Department and other federal agencies.

Overall, subsidized “alternative energy” – largely excluding both nuclear power and natural gas – also provides Silicon Valley with federal backing for ventures in everything from luxury electric cars and dodgy geothermal developments to “smart” energy grids. And, of course, all this increased federal spending also plays into the public-sector unions, for whom an ever-expanding government represents the ultimate growth industry.

In the short term, Obama’s loyalties have gained him political credit even in hard times. Support from Wall Street and Silicon Valley assures access to big-money sources and influences the upper echelons of the establishment press, particularly in New York. Meanwhile, the academy and the public bureaucracy provide a cadre of political shock troops who may be needed to rouse an increasingly disaffected Democratic base in the 2010 elections.

But Obama’s class strategy also poses considerable longer-term risks. The cognitive elites – clustered in places like Washington, New York, Boston, or Silicon Valley – tend to only talk to and listen to each other. This often makes them slow to recognize shifts in grassroots opinion on such issues as the health plan or global warming.

That risks continued erosion of support from many hard-pressed middle-class voters around the country more concerned with economic growth and holding onto their home than saving the planet. These are precisely the voters, not the tea party activists or their leftist analogues, who likely will determine the political winners in 2010 and beyond.

Official White House Photo by Pete Souza.

This article originally appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History

. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.

-

The Football Franchise Hustle: Financing the NFL

The economics of professional football bring more than a few words to mind: scam, hoax, boondoggle, rip-off, racket, con, scheme, fix, subsidy, loophole, ruse, handout, set up, monopoly, and — well, why not — Jimmy Hoffa who, according to urban legend, was interred in the end zone in Giants Stadium.

An insider trading scheme dressed up as a professional sport, pro football finance incorporates everything fishy in the worlds of municipal finance, urban planning, government subsidies, cable television, and, even sometimes, sports.

Let’s move past the idea that professional football is a game played between rival clubs, to test which team is the best over the course of a season. Football may have been that in the 1930s when the Decatur Staleys (later known as the Chicago Bears) were playing the Dayton Triangles. But more recently it has become a hostage to the fortunes of the advertising and investment banking industries, a spectacle put together to sell beer on television or to justify bogus adventures in the bond business.

The evolution from sandlot sport to price-rigged contracts began roughly when its team owners figured out that they all had shares in what Theodore Roosevelt would have called “the football trust.”

Under this cozy arrangement, and with a 1960s anti-trust exemption from the Congress (as if football were as vital to the national interest as bomber production), football owners have parlayed collective television contracts into billions. The next goal was to dress up their new stadiums, largely paid for with public money, as civic virtues.

For a league that prides itself on competition, there is little rivalry tolerated when it comes passing around the money, which amounts to about $8 billion in annual sales. About seventy percent of the television revenue, which amounts to about $4 billion annually, is doled out equally among the thirty-two professional teams, which are best understood as a medieval guild.

In theory, revenue sharing allows the NFL to maintain its competitive balance, so that “on any given Sunday,” one team is capable of beating any other.

Yes, occasionally the Raiders beat the Patriots, but the real advantage of revenue sharing is that it funds an oligopoly of like-minded and greedy owners, who would become small-time operators “on any given Sunday,” were there free enterprise.

If football games were really a sport, and thus closer to a news event, any network with a camera would be allowed to cover any game. The government would be out of the business of regulating sports broadcasts, where permission to broadcast has become simply one more license to be auctioned to congressional and state legislature cronies.

Television revenue also allows team owners to borrow money to build Nuremberg-like stadiums, which can now be seen looming over the warehouse districts in many cities, gothic reminders that team owners are not like you and me.

The boondoggle begins when the franchise owner, protected by his anti-trust herald, says to the city where the team plays that unless he gets a new stadium, the franchise will move elsewhere. Terrified about losing a team more popular than any mayor or council member, the city then condemns prime land for the new construction and authorizes the team’s owner to issue municipal bonds to pay for the new arena.

Many new stadiums, like the retractable-roof mausoleum built near Dallas, cost more than $1 billion, figures that equate professional football economics to the oil depletion allowance, if not the Texas Railroad Commission. On average, taxpayers fund 60 percent of new stadium costs. In the last twenty years, the NFL’s take of taxpayer subsidies has amounted to $17 billion.

Bonds for new stadiums are given tax-exempt status, a folly based on the false premise that these new ballparks are “good for local business.” In truth, they bring in little more than sweetheart construction contracts and the revenue from nearby parking lots. Have a look at what Detroit got for the Silverdome. Hint: it was sold at auction for $583,000, after Detroit dropped in about $200 million in present-value dollars.) The real money goes to the team owner, that beacon of urban renewal.

In some cases, local sales taxes are increased so that stadiums can be financed. But that doesn’t mean consumers get to share in skybox revenues, which the owner keeps for himself and his uptown pals.

Skyboxes, which can cost up to $500,000 per season, are rented to corporations, who use them for tax-deductible wining and dining. “Lucky” fans get to subscribe to “personal seat licenses,” which cost anywhere from $4,000 to $30,000 per seat so that fans then have the “right” to buy season tickets, which might cost another $500 a game.

Given all the money washing around the closed-shop of the NFL, it is little wonder that the value of most franchises is approaching $1 billion, even for hopeless teams like the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Forbes estimates their worth at $1.1 billion, about four times their revenue, and a nearly infinite multiple of their recent wins.

What do the players get from these financial bubbles? To be sure, some of the stars get millions in guaranteed money on multi-year contracts. The rest can be cut at the whim of the owners (“to clear cap space”), with little to show for their prime-time performances except crippling injuries, addiction to pain killers, and very possibly early dementia.

Thanks to a $127 million salary cap (dressed up to trumpet “fair competition”), player salaries will never be more than shared TV revenues. This arrangement makes the league immune from team failures and gives teams like the Buffalo Bills an incentive to lose gracefully and cheaply.

In 2008, Buffalo earned $40 million, while the Dallas Cowboys reported only $9 million. Average team revenue in the league was $237 million, and average net profit was $32 million per team.

Will professional football’s wheel of fortune spin forever? Will someday soon every team have a billion dollar stadium, upholstered skyboxes, fat television revenue sharing, tax-exempt debt, and fixed costs for its players, who stay on the job for less time than migrant workers?

Maybe, but here’s how I think the free market will take “the football trust” to the house, if not the cleaners.

One of these days television revenue will decline, when networks can no longer afford the billion dollar contracts; their advertisers will have departed to other fields of plenty. Would you want CBS and NBC as your biggest source of revenue? At the same time, voters will wake up to find that their municipalities have gone broke and that much local interest is due on behalf of behemoth stadiums — often named after get-out-of-town-quick companies, like Enron — that most voters cannot afford to visit.

Like a number of monopolies, the NFL might find itself under pressure in the courts, and the league could lose some of the pricing power that comes from the protectionism that is courtesy of the cable owners, the municipal bond fixers, and the Congress.

If any city in the country could field a professional team, and if any broadcaster was free to show the games, would cities be building new stadiums that cost $1 billion and would the woeful Washington Redskins be worth $1.5 billion? I don’t think so. But right now the NFL is the only game in town.

Matthew Stevenson is author of An April Across America

and the soon to be published Remembering the Twentieth Century Limited.

-

New Geography Top Stories of 2009

As we bring to a close our first full calendar year at NewGeography.com, we thought readers may be interested in which articles out of more than 350 published enjoyed the widest readership. It’s been a solid year of growth for the site; visits to the site over the past six months have more than tripled over last year and subscribers have increased by a factor of six. The list of popular articles is based both on.readership online and via RSS.

15. Joel Kotkin’s piece, Numbers Don’t Support Migration Exodus to “Cool Cities”, makes the case that places considered “cool” by many in media and economic development circles are actually losing net migrants to other U.S. regions. In almost every case, he argues, your local resources are better spent focused on skills upgrades for your local residents or hard and soft infrastructure upgrades for industries already successful in your region. This article originally appeared on Forbes.com

14. The British Labour Party is no example for American Progressives. Legatum Institute Senior Fellow Ryan Streeter’s piece just in time for the 4th of July, View from the UK: The Progressive’s Dilemma, dissects Britain’s high social spending, increasing debt load. Streeter contends that the UK is danger of mortgaging its future.

13. Breaking down Obama’s first year and looking forward. In two equally popular pieces from this fall, Joel Kotkin outlines a five point plan to improve Obama’s presidency (Obama Still Can Save His Presidency which originally appeared in Forbes.com. In the second piece he takes encouragement from signs that the President may be retuning his policy back towards America – “a big, amazingly diverse country with an expanding population” – and away from the “Scandinavian Consensus” model (Is Obama Separating from His Scandinavian Muse?) . This article originally appeared on Politico.com.

12. State of the economy June 2009. Susanne Trimbath says it may be a while before the average citizen will actually see tangible improvements in the economy. As is often the case, Susanne’s predictions have turned out so far to be all too accurate.

11. Questioning the stimulus plan. In February’sStimulus Plan Caters to the Privileged Public Sector, Joel Kotkin calls the stimulus plan “a massive bailout and expansion of the public-sector workforce as well as quasi-government workers in fields like health and education” yet “as little as 5% of the money is going toward making the country more productive in the longer run – toward such things as new roads, bridges, improved rail and significant new electrical generation.” This article originally appeared in Forbes.com

10. Is California’s economic malaise leaking into Oregon? After years of strong migration flows of former Californians heading to Oregon, Joel Kotkin and California Lutheran University economist Bill Watkins point out that the state’s oppressive tax policies and red tape may be leaking into Oregon as well in California Disease: Oregon at Risk of Economic Malady. The article originally appeared in The Portland Oregonian.

9. Tracking housing decline. Wendell Cox broke down the comparative national housing market in two widely read pieces. In the first he points out that the downturn can be broken into two phases, one mirroring the explosive growth in many overvalued markets, and another second phase were markets are declining across the board: Housing Downturn Moves Into Phase II. In the second, Wendell uses his median multiple calculation for the 49 largest metropolitan regions to show that prices in many place still have much farther to fall to reach historic norms: Housing Downturn Update: We May Have Reached Bottom, But Not Everywhere.

8. Public debt is looming. Susanne Trimbath lists public debt levels of the most highly leveraged sovereign nations and explains why this debt and the credit default swaps purchased against it could create a looming public catastrophe: The Next Global Financial Crisis: Public Debt.

7. Washington, DC is flourishing in the recession. NYU Professor and urban commentator Mitchell Moss explains how Washington is the one city benefiting from the government stimulus. He argues this is stimulating the DC economy, from increased lobbyist activity to web designers benefiting from the government’s new interest in digital communications: Washington, DC: The Real Winner in this Recession.

6. Californa’s Decline. Three equally widely read pieces track the drastic shift in California from economic vibrancy to stagnancy: Kotkin’s “Death of the California Dream which ran first in Newsweek and The Decline of Los Angeles from February on Forbes.com. The third piece by economist Bill Watkins examines California’s domestic migration net losses using an old coal mining metaphor: In California, the Canary is Dead.

5. Housing Affordability Rankings. The most read housing piece this year was Wendell Cox’s release of his annual housing affordability rankings based on median multiple calculations (ratio of median housing price to median household income in a given market). “Housing Prices Will Continue to Fall, Especially in California” lists median multiple calculations for each metropolitan region in the U.S. of more than 1,000,000 population.

4. Detroit as a model for urban renewal. In a widely linked piece across the blogosphere, Aaron Renn points out that the decline in Detroit could be a platform for residents to get creative with urban re-development. This piece is full of stunning imagery of formerly dense neighborhoods now full of greenspace that sent me on a two hour Google Earth binge exploring the area. Detroit: Urban Laboratory and the New American Frontier.

3. ”Alternative” Geography. New Geography publisher Delore Zimmerman’s run down of odd and quirky maps that redefine borders of the U.S. proved very popular on social bookmarking sites. “Borderline Reality”: “Sometimes maps can inspire and motivate us by helping to more fully understand the geography of our economic and demographic challenges and opportunities. Perhaps most importantly thematic maps tell a story about places.”

2. Portland isn’t a model for every community. Easily our most widely discussed, shared, and linked piece this year was Aaron Renn’s “The White City.” The piece sparked a fair amount of criticism with some looking to poke holes in the racial breakdowns and others taking the piece as an affront to liberal politics instead of an examination of urban planning policy. Many of the most vehement critics failed to address the central point of the piece: Portland is a unique place with a unique disposition and composition, yet it is held up by many community leaders in other regions as the ultimate in public policy. Instead of holding up Portland as a model, cities and regions need to do a better job of looking at themselves and defining policy based upon local community identity. Be who you are.

1. Best Cities Rankings. Overall, our most read content at New Geography this year was the Best Cities Rankings, released in April with Forbes. Our rankings are purposefully focused just on a combination of measures of one metric, employment change. We leave out all of the more qualitative measures thinking that all contribute to the output of a shifting employment landscape.

Where are the Best Cities for Job Growth? (Summary Piece)

2009 How We Pick the Best Cities for Job Growth

All Cities Rankings – 2009 New Geography Best Cities for Job GrowthIt’s been a good year at New Geography, one of steady growth and, we believe, increased influence. We welcome your comments, participation, and submissions. Thanks for reading.

-

How California Went From Top of the Class to the Bottom

California was once the world’s leading economy. People came here even during the depression and in the recession after World War II. In bad times, California’s economy provided a safe haven, hope, more opportunity than anywhere else. In good times, California was spectacular. Its economy was vibrant and growing. Opportunity was abundant. Housing was affordable. The state’s schools, K through Ph.D., were the envy of the world. A family could thrive for generations.

Californians did big things back then. The Golden State built the world’s most productive agricultural sector. It built unprecedented highway systems. It built universities that nurtured technologies that have changed the way people interact and created entire new industries. It built a water system on a scale never before attempted. It built magnificent cities. California had the audacity to build a subway under San Francisco Bay, one of the world’s most active earthquake zones. The Golden State was a fount of opportunities.

Things are different today.

Today, California’s economy is not vibrant and growing. Housing is not affordable. There is little opportunity. Inequality is increasing. The state’s schools, including the once-mighty University of California, are declining. The agricultural sector is threatened by water shortages and regulation. Its aging, cracking, highways are unable to handle today’s demands. California’s power system is archaic and expensive. The entire state infrastructure is out of date, in decline, and unable to meet the demands of a 21st century economy.

Indications of California’s decline are everywhere. California’s share of United States jobs peaked at 11.4 percent in 1990. Today, it is down to 10.9 percent. In this recession, California has been losing jobs at a faster pace than most of the United States. Domestic migration has been negative in 10 of the past 15 years. People are leaving California for places like Texas, places with opportunity and affordable family housing.

California’s economy is declining. Those of us who live here can all see it. Yet, Californians don’t have the will to make the necessary changes. Like a punch-drunk fighter, sitting helpless in the corner, California is unable to answer the bell for a new round.

Pat Brown’s California – between 1958 and 1966 – crafted the Master Plan for Higher Education, guaranteeing every Californian the right to a college education, a plan that has served the state very well. That system is threatened by today’s budget crisis and may be on the verge of a long-term secular decline. California was a state where people said yes, a state where businesses could be created, grow, and prosper. Some of these businesses were run by Democrats, others Republicans but all celebrated a culture of growth and achievement.

Today’s California is a state where building a home requires charrettes with the neighbors, years in the planning department, architects, engineers, and environmental impact studies – we built the transcontinental railroad in three years, faster than a builder can get a building permit in many California communities. People here dream of a green future but plan and build nothing. There’s big talk about the future, but California now turns more and more of our children away from college, and too many of our least advantaged children don’t even make it through high school.

Once, California was a political model of enlightened government. Now it’s a chaotic place where everyone has a veto on everything; a state where people say no; a state where business is wrapped up in bureaucracy and red tape; a state our children leave, searching for opportunity; a state with more of a past than a future.

Some things have not changed. California’s physical endowment is still wonderful. The state is blessed with broad oak-studded valleys, incredible deserts, magnificent mountains, hundreds of miles of seashore, and an optimal climate. California’s location on the Pacific Rim situates the state to profit from growing international trade with the dynamic Asian economies. California didn’t change, Californians changed. Californians have forgotten basics that Pat Brown knew instinctively.

How did California get to this point? How did it move from Pat Brown’s aspirational California to today’s sad-sack version? What did Pat Brown know in 1960 that Californians now forget?

First thing: Pat Brown knew that quality of life begins with a job, opportunity, and an affordable home. Other Californians in Pat Brown’s time knew that too. His achievements weren’t his alone. They were California’s achievements.

It seems that California has forgotten the fundamentals of quality of life. Instead, the state has embraced a cynical philosophy of consumption and denial. The state’s affluent citizens celebrate their enjoyment of California’s pleasures while denying access to those less fortunate, denying not only the ticket, but the opportunity to earn the ticket. At best California offers elaborate social services in place of opportunity.

Today, too many Californians don’t rely on the local economy for their income. For them, quality of life has nothing to do with jobs, opportunity, or affordable homes. Many see the creation of new jobs as bad, something to be avoided. They see no virtue in opportunity. They have theirs, after all. It is their attitude that if someone else needs a job, let them go to Texas; if people are leaving California, so much the better.

They see someone else’s opportunity as a threat to them. Perhaps the upstarts will want a house, which might obstruct their view. They see economic growth as a zero sum game. Someone wins. Someone loses.

This type of thinking is unsustainable. Opportunity is not a zero sum game. It may be a cliché, but it is true, that if something is not growing it is dying. Many of the things that make California the place it is are not part of our natural endowment. The Yosemite Valley is part of the state’s natural endowment, but the Ahwahnee Hotel is not. Monterey, Santa Barbara, San Francisco, the wine countries, and California’s many other destinations were made possible and built because of economic growth. Will California add to this impressive list in the 21st century?

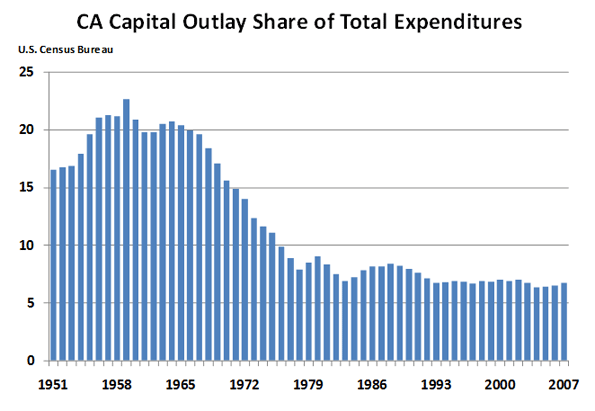

Not likely. Today, we are not even maintaining our infrastructure. Infrastructure investment’s share of California’s budget has declined for decades. In Pat Brown’s day California often spent over 20 percent of its budget on capital items. Today, that number is less than seven percent. It shows.

Pat Brown also knew that with California’s natural endowment, all he had to do was build the public infrastructure and welcome business, business will come. Too many today act as if they believe that business will come, even without the infrastructure or a welcoming business climate. Indeed, many Californians – particularly in the leadership in Sacramento – seem to think that business will come no matter how difficult or expensive the state makes doing business in California. This is just not true.

California needs to embrace opportunity and economic growth. It is necessary if California is to achieve its potential. It is necessary if California is to avoid a stagnant future characterized by a bi-modal population of consuming haves and an underclass with little hope or opportunity and few choices, except to leave.

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org.

-

More Money for Bailout CEOs

The day before leaving town to vacation in an opulent $9 million, 5-bedroom home in Hawaii, the Obama administration pledged unlimited financial support for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The mortgage giants are already beneficiaries of $200 billion in taxpayer aid. On Christmas Eve, regulatory filings reported that the CEOs of the two firms are in line for $6 million in compensation. Merry Christmas!

Executive compensation is the subject of many academic studies, but one focused on Fannie Mae from two Harvard Law School professors is especially well-named: “Perverse Incentives, Nonperformance Pay and Camouflage”. Executives are able to take unlimited risks and reap unlimited upside rewards knowing that US taxpayers will foot the bill on the downside. The mortgage-backed securities issued by the two firms remain at the center of the causes-and-effects of the financial meltdown.

The compensation for Fannie Mae’s senior managers is recommended by the Compensation Committee “in consultation and with the approval of the Conservator”, which is the U.S. Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). The FHFA was created in July 2008 when Bush signed the Housing and Economic Recovery Act. At the time, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the $200 billion Act would save 400,000 homeowners – in the first six months, exactly one homeowner was able to refinance under the program. The Act also was supposed to clean up the subprime mortgage crisis – which it did not do as evidenced by the collapse of the global financial markets a few months later.

Back to the current problem of paying $6 million to run a bankrupt company whose every financial obligation is guaranteed by taxpayer money. Who is on the compensation committee that recommended this pay day? Dennis Beresford from Ernst & Young (E&Y); Brenda Gaines, recently from Citigroup; Jonathan Plutzik, from Credit Suisse First Boston; and David Sidwell, from Morgan Stanley.

Back in 2004, Ernst & Young was engaged as a consultant to Fannie Mae – right after the Securities and Exchange Commission banned E&Y from taking on new clients. Citigroup took $25 billion in TARP bailout money and Morgan Stanley took $10 billion. Credit Suisse benefited by a mere $400 million as their share of the AIG Financial Products group bailout. Needless to say, this Compensation Committee knows a thing or two about controversies and federal aid!

Enjoy your luxury Christmas vacation, Mr. President, while 45 out of 50 U.S. states are enjoying statistically significant decreases in employment in the face of rising prices. Please take some time to contemplate the words GE Chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt used in describing the leadership traits that need to change in America: “The richest people made the worst mistakes with the least accountability.”

And to the rest of you out there reading this, take some time to contemplate the words of Bill Moyers as he concluded a rather shocking essay of the role of lobbyists in the recent “healthcare reform” legislation: “Outrageous? You bet. But don’t just get mad. Get busy.”