One of the great pleasures of China is a walk along the Bund promenade.

Shanghai’s Bund is one of China’s great tourist and historic sites. Its history lessons are from two distinctively different periods. All of this can be witnessed from the raised promenade along the west bank of the Huang Pu River, which separates the old Puxi (west of the river) commercial core of Shanghai from the new, iconic business district that has grown up in Pudong (east of the river). It is clear that the promenade at the Bund is a very popular local tourist attraction as well.

The Bund became a center of British commerce in the mid-19th century and remained a part of the Shanghai International Settlement (through a 1860s merger of the British and American concessions) until the beginning of World War II. Most of the buildings were built in the first quarter of the 20th century.

This article will provide a quick tour of the western style buildings in Puxi, behind the promenade and a few views of Pudong (the Lujiazui business district) across the river. The tour starts at the south end of the Bund and continues approximately 1.2 kilometers (0.75 miles) to Suzhou Creek, just beyond the north end of the Bund. The western buildings are located along Zhongshan East #1 Road, facing the Huang Pu. The promenade is between the buildings and the Huang Pu, across from which is the Lujiazui business district of Pudong. Generally, the names used for the buildings are the original or pre-World War II, though the there can be conflicting names. I would be pleased to be advised of any corrections.

Image 1 shows a broad sweep of the central Bund from the south to north. It includes the four most iconic buildings.

The Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) Building is the large domed building near the left of the picture. It was constructed in 1923 and served as the local branch of this UK bank until 1955, six years after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. When the bank left, it ceded title to the Shanghai People’s Government, which used the building as its headquarters for some years. It is now the Shanghai Pudong Development Bank Building.

The Customs House is just to the north of the Shanghai Pudong Development Bank Building, with the tall clock tower was opened in 1927.

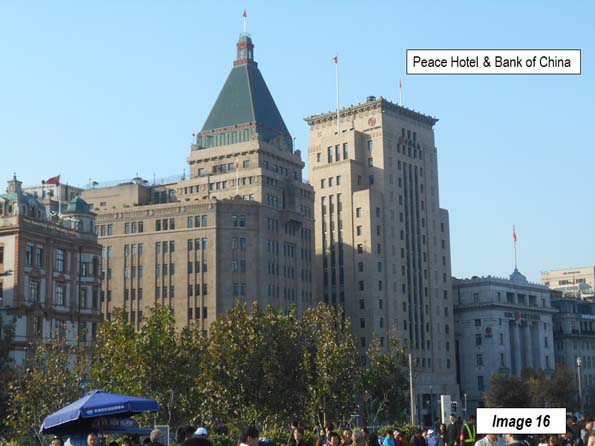

The Peace Hotel is farther north, with the green peaked tower. It was originally the Sassoon Hotel and was the north building of the hotel complex. It is now the Fairmont Peace Hotel. Across the street, is the south building of the Peace Hotel, now called the Swatch Art Peace Hotel.

The Bank of China Building is just to the north of the Peace Hotel. Construction began on the building in the mid-1930s and it was opened after the start of World War II, in 1942.

The illustrations start at the south end of the Bund, just north of the Pudong Ferry Terminal

Image 2: Asia Building

Image 3: Shanghai Club

Image 4: Union & Nish in Navigation Buildings

Image 5: Nishin Navigation & China Merchants Bank Buildings

Image 6: Great Northern Telegraph to HSBC Building

Image 7: Great Northern Telegraph & Bund #6

Between Bund #6 and the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank Buildings, Fuzhou Road reaches Zhongshan Road. Fuzhou Road has been known for its bookstores, though there have been fewer in recent years.

Image 8: Original Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank (HSBC) Building, now Shanghai Pudong Development Bank.

Image 9: HSBC Bank & Customs House Buildings

Image 10: Customs House and buildings to the south

Image 11: Customs House

Image 12: Bank of Shanghai & Russo-Chinese Bank

Image 13: Russo-Chinese Bank, Bank of Taiwan (original name, Taiwan was occupied by Japan when built) and the North China Daily News buildings. The North China Daily News was the leading English newspaper of China until it closed at the beginning of World War II.

Image 14: Bank of Taiwan, North China Daily News & Chartered Bank

Image 15: North China Daily News Peace Hotel South Building, Peace Hotel (North) and Bank of China buildings

The Peace Hotel north and south buildings are across Nanjing Road opposite one another. Nanjing Road is an important shopping street, and a few more blocks inland becomes a pedestrian mall. It is also famous for offers from local students to join them in tea drinking ceremonies or at art exhibitions at which they claim to have work on display. This can be a costly experience and is not recommended.

Image 16: Peace Hotel (North) and Bank of China

Image 17: Peace Hotel (North) and Bank of China

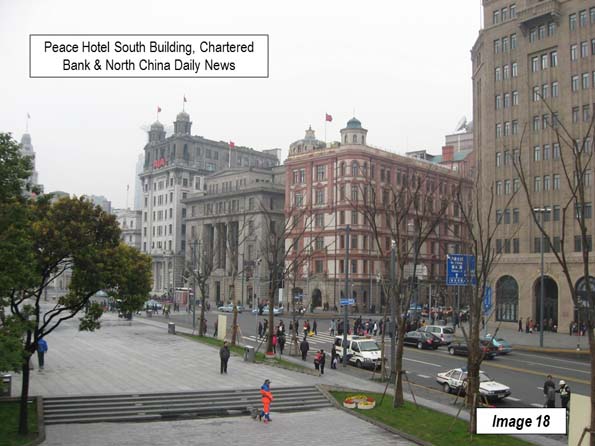

Image 18: South from Peace Hotel (North) to North China Daily News

Image 19: Yokohama Specie Bank and Yangtze Insurance buildings

Image 20: Jardine Matheson, Yangtze Insurance, Yokohama Specie Bank and Peace Hotel (north and south buildings). Jardine Matheson was an early trading company that got its start in Guanghou (Canton) and Hong Kong.

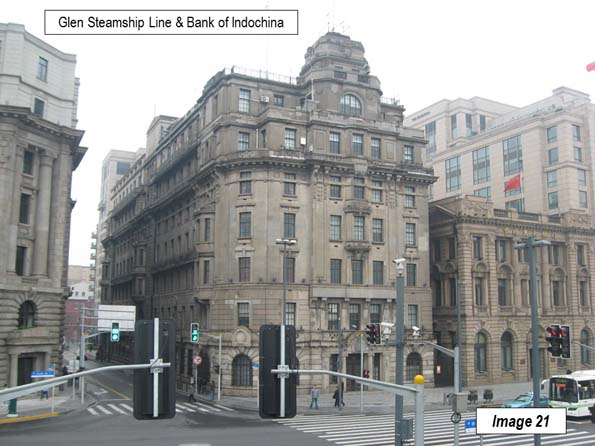

Image 21: Glen Steamship Lines and Bank of Indochina

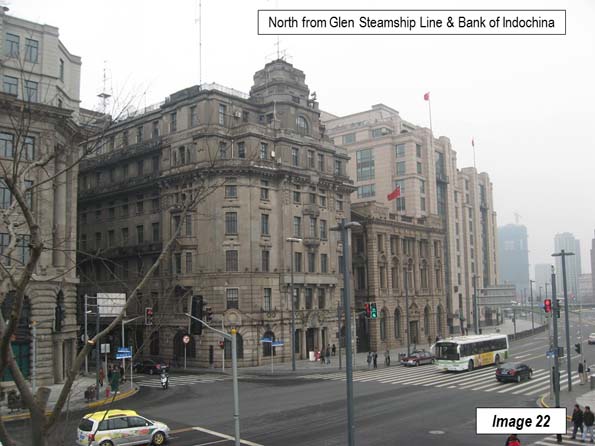

Image 22: North end of the historic bund buildings on Zhongshan Road (Glen Steamship Lines and Bank of Indochina).

Image 23: Waibaidu Bridge over Suzhou Creek, Broadway Mansions and Russian Consulate

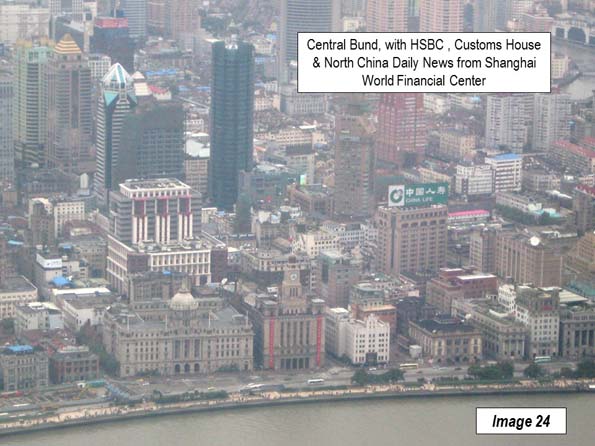

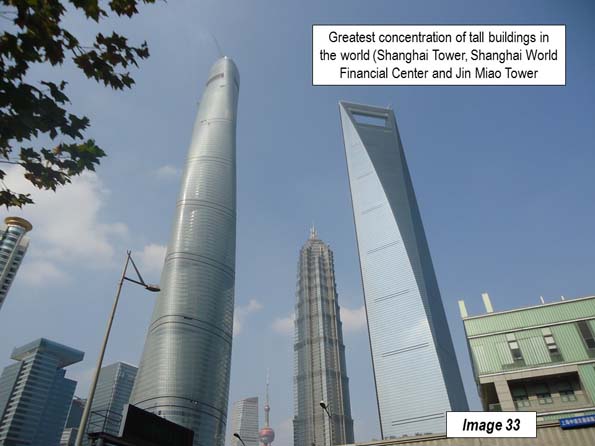

Image 24: Central Bund, including HSBC, Customs House and North China Daily News buildings from the World Finance Centre. The Shanghai World Finance Center has an opening at the top and locals refer to it as the “bottle opener” for its resemblance (Image 33).

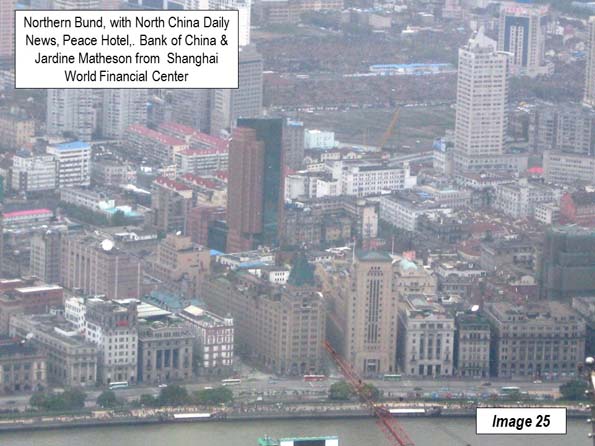

Image 25: Northern Bund, including North China Daily News, Peace Hotel, Bank of China and Jardine Matheson Buildings from the Shanghai World Financial Tower.

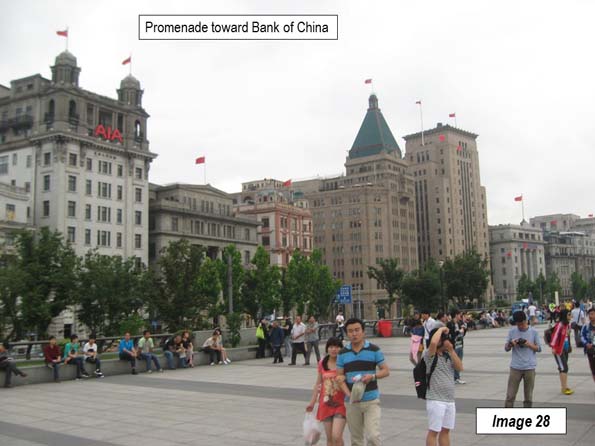

Images 26 to 28: Promenade views

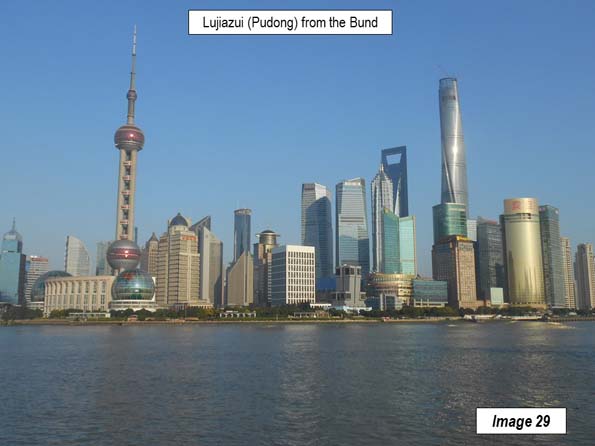

Image 29: View of Pudong’s Lujiazui business district from the Bund promenade (across the Huang Pu). The Pearl of the Orient Tower is to the left. The tallest building, on the right, is the Shanghai Tower, second tallest building in the world (127 stories).

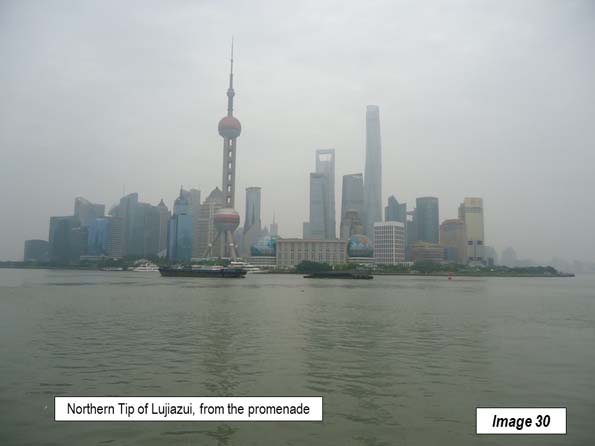

Image 30: Northern tip of Lujiazui business district from the promenade

There are a number of additional Western-style buildings that were a part of the International Settlement in Puxi. Many are on the East – West streets leading from Zhongshan Road as well as on some North – South streets, such as Sichuan Middle Road. Some buildings of the same era are located on Nanjing Road. The Park Hotel, located across the street from People’s Park was the tallest building in Asia when it was built in 1934 (Image 31), and may be the best known local hotel, along with the Peace Hotel, on the Bund.

The Bund is close to other interesting tourist areas. The Yu Garden dates to the 16th century and is the very architectural conception of China for some tourists. As Chinese as is its appearance, not much of Chinese cities looks like this. Yu Garden now hosts extensive shopping, as well as the Huxinting Teahouse (Image 32, at night).

The Bund sightseeing tunnel provides a short rail service from East Beijing Road (across the street from the Bank of China) under the Huang Pu to Lujiazui, near the Pearl of the Orient Tower. From there overhead walkways provide access to Lujiazui skyscrapers, include the three tallest (Image 33), which are virtually across the street from one another. These include the Shanghai Tower (second tallest in the world), the Shanghai World Financial Center and the shortest, the Jin Miao Tower, which is taller than the Empire State Building in New York and nearly as tall as the Willis Tower (former Sears Tower), in Chicago, the tallest in the world for a quarter of a century.

From here, it is a short walk to the ferry terminal for a short right to the south end of the Bund (Image 34), completing the circle tour that began with Image 2.

Finally, the Bund promenade is also a very well designed urban space that has become one of Shanghai’s most important public meeting spaces. It is well appointed with places to sit, relax or read a book. Like Le Jardine du Luxembourg in Paris and New York’s Central Park, there are few places to better spend a Saturday afternoon.

Photograph at Top: Central Bund (Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank and Customs House), by author

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.