Blog

-

Honest Services From Bankers? Increasingly Not Likely

Once you understand what financial services are, you’ll quickly come to realize that American consumers are not getting the honest services that they have come to expect from banks. A bank is a business. They offer financial services for profit. Their primary function is to keep money for individual people or companies and to make loans. Banks – and all the Wall Street firms are banks now – play an important role in the virtuous circle of savings and investment. When households have excess earnings – more money than they need for their expenses – they can make savings deposits at banks. Banks channel savings from households to entrepreneurs and businesses in the form of loans. Entrepreneurs can use the loans to create new businesses which will employee more labor, thus increasing the earnings that households have available to more savings deposits – which brings the process fully around the virtuous circle.

As U.S. households deal with unemployment above 10% as a direct result of the financial crises caused by excessive risk-taking at banks, one bank, Goldman Sachs, posted the biggest profit in its 140-year history. According to Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz at Columbia University, Goldman’s 65% increase in profits is like gambling – the largest growth came from its own investments and not from providing financial services to households and businesses.

Under fraud statutes created in 1988, Congress criminalized actions that deprive us of the right to “honest services.” The law has been used generally to prosecute fraudsters and potential fraudsters – from Jack Abramoff to Rod Blagojevich – whenever the public does not get the honest, faithful service we have a right to expect.

The theory of “honest services” was used in one of the best known U.S. cases of financial misbehavior – Jeff Skilling of Enron – who has been granted a hearing early next year with the U.S. Supreme Court on the subject. Prosecutors won the original 2006 conviction on the strategy “that Skilling robbed Enron of his ‘honest services’ by setting corporate goals that were met by fraudulent means amid a widespread conspiracy to lie to investors about the company’s financial health.” The U.S. Attorney argued that CEO Skilling set the agenda at Enron. In this case, the fraud and conspiracy were means by which corporate ends were met.

Skilling’s defense attorney admitted in his appeal before the 5th Circuit in April that his client “might have only bent the rules for the company’s benefit.” The appeal was not granted – a move by the court that is viewed as an overwhelming success for the prosecution. The application of the theory of “honest services” to the Skilling case – targeting corporate CEOs instead of elected officials – has been the subject of debate which may explain why the Supreme Court agreed to hear the arguments.

Regardless of the outcome of that or other cases on the subject, the fact remains that bankers are doing better for themselves than they are for American households. This is the number one complaint we have about banks today. If I had to summarize the rest of what bothers us about banks, I would start with the fact that they are secretive. They take advantage of a very common fear of finance to convince consumers that they know what’s good for you better then you do.

Next in line is the fact that they have purchased Congress. Banks have access to the halls of power that – despite 234 years of egalitarian rhetoric – ordinary voters can never achieve. Finally, we resent banks because we are required to use their services, like a utility, to gain access to the American Dream.

Financial services contribute about 6 percent to the U.S. economy. Manufacturing and information industries use financial services, but the industry increasingly depends on itself: recall the portion of Goldman’s earnings growth coming from using its own investment services. According to the latest data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the financial services industry requires $1.27 of its own output to deliver a dollar of its final product to users. Despite the fact that our economic reliance on financial services has been creeping up steadily since 2001, they remain one of the least required inputs for U.S. economic output – only wholesale and retail trade have less input to the output of other industries.

So, why did Congress vote them nearly a trillion dollars worth of life-support bailout money at the expense of taxpayers? Why did Wall Street get swine flu vaccine ahead of rural hospitals and health care workers? Why did they get the bailout without accountability? By making banks account for what they did with the money, congress could have 1) prohibited spending on bonuses and lavish retreats; 2) ensured improved access to credit for small and medium enterprises; and 3) provided transparency to taxpayers on who got how much and what they did with it. Need more reasons to demand honest services from a banker? Try this list:

- Congress raised the FDIC insurance to $200,000 to make depositors comfortable leaving money in banks; then the banks passed the insurance premium on to customers – including those that never had $200,000 cash in the bank in their lives and probably never will. Seriously, how much money do you have to have before it makes sense to have $200,000 in cash in a savings account earning 0.25%?

- Banks can borrow at 0% from the Fed yet they raise the interest rates they charge even their best customers. The bank I use for my company willingly lent me $10,000 last year to open a new office and approved a $7,000 credit card limit. Last month they sent me a letter saying they are raising the interest rate by +1.9 percentage point – though I have never missed a payment deadline.

- The banks can use our deposits to purchase securities issued by the Federal government, which are yielding better than 3 percent. They pay us about 0.25 percent yet still find it necessary to tack on a multitude of fees – which amount to 53 percent of banks’ income today, up from 35 percent in 1995.

For now, Brother Banker skips along as lively as a cricket in the embers. But remember this: Marie Antoinette didn’t know anything about the French revolution until they cut off her head. Matt Taibbi, in a recent Rolling Stone article called Goldman Sachs a “great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” We are at risk for leaving the virtuous circle behind and entering a vicious circle of spiraling inflation. A massive increase in government debt is being paid down by printing more money. Between July 2008 and November 2008, the Federal Reserve more than doubled its balance sheet from $0.9 trillion to $2.5 trillion. A year later, there is no evidence that they are trying to rein it in. As Brother Banker fails to provide honest services, a briar patch of a different kind may be waiting around the corner.

Susanne Trimbath, Ph.D. is CEO and Chief Economist of STP Advisory Services. Her training in finance and economics began with editing briefing documents for the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. She worked in operations at depository trust and clearing corporations in San Francisco and New York, including Depository Trust Company, a subsidiary of DTCC; formerly, she was a Senior Research Economist studying capital markets at the Milken Institute. Her PhD in economics is from New York University. In addition to teaching economics and finance at New York University and University of Southern California (Marshall School of Business), Trimbath is co-author of Beyond Junk Bonds: Expanding High Yield Markets

.

-

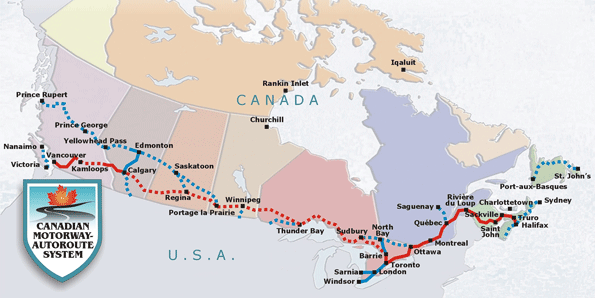

A Canadian Autobahn

Canada is the largest high-income nation in the world without a comprehensive national freeway (autobahn, expressway or autoroute) system. Motorways are entirely grade separated roadways (no cross traffic), with four or more lanes (two or more in each direction) allowing travel that is unimpeded by traffic signals or stop signs.

The Economic Advantages of Motorways: Motorways have been associated with positive economic and safety impacts. For example, a synthesis of research by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) noted the positive impact of US motorway system:

The Interstate Highway System represented an investment in a new, higher speed, safer, lower cost per mile technology which fundamentally altered relationships between time, cost, and space in a manner which allowed new economic opportunities to emerge that would never have emerged under previous technologies.

In particular, the AASHTO synthesis indicated that motorway

…investments have lowered production and distribution costs in virtually every industry sector.

It is a well known fact that motorways are by far the safest roads. We estimated that 187,000 fatalities had been averted due to the transfer of traffic from other roads to motorways between 1956 and 1996.

A World of Motorways: Truckers in Japan, Europe (the EU-15) and the United States can travel between virtually all major metropolitan areas on high quality motorways.

Further, motorway systems have and are being built in developing nations. By far the most impressive is China, which now has approximately 65,000 kilometers of motorway, not including motorways administered at the municipal level (as in Shanghai and Beijing). Only the United States has more, at approximately 85,000 kilometers. China’s plans call for the US figure to be exceeded within a decade. These roads are being built not only throughout populous eastern and central China, but also to the Pamirs at the Kazakh border and to Lhasa, in Tibet, across some of the most desolate and sparsely populated territory in the world. Mexico, a partner with Canada and the United States in the North American Free Trade Agreement also has an extensive motorway system.

Motorways in Canada: Canada, however, is an exception. Only a quarter of metropolitan areas are connected to one another by motorways. Edmonton and Calgary are among the few metropolitan areas in the developed world that are not connected to comprehensive motorway systems (Vancouver is connected to the US system, but not to the rest of Canada).

For many trips between Canadian metropolitan areas, it takes less time to travel through the United States on its motorways than on the Canadian roads (such as between Winnipeg or Calgary and Toronto). The principal problem is the long, crowded, slow, two-lane stretch of roadway through the northern Great Lakes region between the Manitoba-Ontario border and between Sudbury and Parry Sound. There is also a long section of roadway in the British Columbia interior that a Calgary talk show host referred to as a “stagecoach” trail. Canada pays an economic price for this lack of a world-class highway system, both in terms of manufacturing and tourism.

However, parts of Canada are well served by motorways. Much of central and eastern Canada is connected by motorways, with routes from Windsor, Ontario, through Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Quebec to Halifax. This route includes only a short segment that is not motorway standard in the province of Quebec as it approaches the New Brunswick border.

Moreover, despite its reputation to the contrary, the largest Canadian urban areas have world class freeway systems. Few, if any, urban areas in the United States or the developed world have more kilometers of motorway or motorway lanes in relation to their urban area size as Toronto and Montreal.

A Canadian Autobahn: In cooperation with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, we proposed a world class highway system for Canada. In a report entitled “A Canadian Autobahn: Creating a World Class Highway System for the Nation” we proposed:

- Upgrading the entire transcontinental route from Halifax, through Toronto to Vancouver to motorway standards. These improvements should be completed within 10 years and would cost approximately $28 billion (2009$).

- Upgrading other principal routes to at least pre-motorway standard, which would require “twinning” (four-lanes) and minimizing the number of grade crossings. The longest of these additional highways is the Yellowhead route: Edmonton and Calgary to the Canada-U.S. border; Ottawa to Sudbury; and across the island of Newfoundland. These improvements should be completed within 15 years and would cost approximately $33.5 billion).

The transcontinental route would provide a long overdue economic stimulus to urban areas such as Thunder Bay and Sault Ste. Marie. The improved Yellowhead route would provide far better access to the new deepwater, superport at Prince Rupert (British Columbia), which is the closest North American port with connections to major Asian markets. This could materially improve Prince Rupert’s competitiveness relative to larger ports on the US West Coast, such as Los Angeles and Long Beach (which have become much less competitive themselves in the last decade). The improved roadway would make it possible to effectively serve the markets of the US Midwest, South and East through a connection to I-29 in North Dakota.

The report was unveiled at a Calgary event on October 29 and was covered by media across the nation.

What About Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A question was raised about the advisability of expanding highways at a time that the world is attempting to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Such a strategy would seem to be at odds with the popular perception that we shall all have to abandon our cars and move into flats in the central city. This perception presumes that people are prepared to return to the standards of living and lifestyles of 1980, 1950 or even 1750. In all of my presentations on similar issues I am yet to uncover any groundswell of support for the lifestyles of yesterday.

It needs to be recognized that the international commitment to reducing GHGs is based upon an assumption of minimal impact on the economy. GHG reductions will be achieved only if they are acceptable to people, which requires acceptable costs (research by the United Nations International Panel on Climate Change suggests an upper bound of $50 per ton). Cost effectiveness is necessary to not only prevent a huge increase in poverty, but also to allow continued progress toward poverty alleviation and upward mobility. In fact, as recent US research indicates, there is scant real world potential to reduce GHGs from reduced levels of driving.

Given the strong association between economic growth and personal mobility, there is a single realistic path to substantial GHG emission reduction: better technology. Fortunately, developments suggest that technology is, indeed, the answer.

The question, thus, comes down to whether jobs in the northern Great Lakes region (and elsewhere) are more important than strategies that are politically correct, but comparatively ineffectual with respect to materially reducing GHG emissions. It seems likely that people will place a priority on jobs.

Finance: Because of the importance of tying the nation together, it would be appropriate to spend federal and provincial funds on the Canadian Autobahn. User fees, such as a dedicated gasoline tax (as in the United States) or tolls (as in France, China and Mexico) could finance the expansions, using public-private partnerships or “arms-length” government corporations.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

”

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN on Docudharma regarding Works Progress Administration

“Unemployment today may not be as extreme as in the 1930s, but for whole segments of the population–notably young workers under 25–it is on the rise. Already young workers with college educations suffer a 7.7% jobless rate, while employment is nearly twice that among young workers overall. Hardest hit, in fact, are young people without college educations, whose real earnings already have dropped by almost 30% over the past 30 years, according to one study. ”

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN on Prairie Business regarding cities

“Joel Kotkin, a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University in California and a senior consultant with the Grand Forks-based Praxis Strategy Group, says larger cities like Bismarck, Sioux Falls, Fargo and Grand Forks and smaller communities within a 50-mile radius look to be well positioned for the future. But he adds that the farther away you get from air service and key infrastructure, the more challenging the situation becomes for rural communities.”

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN on The Grant Forks Herald regarding California

“The article features this quote from Joel Kotkin, a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University in California. ‘Twenty years ago, you could go to Texas, where they had very low taxes, and you would see the difference between there and California,’ Kotkin told the Times.”

-

Reducing Carbon Should Not Distort Regional Economies

A pending bill in Congress to reduce carbon emissions via a “cap and trade” regime would have significant distorting effects on America’s regional economies. This is because the cost of compliance varies widely from region to region and metro to metro. This is all the more important since such legislation may do very little to reduce overall carbon emission according to two of the EPA’s own San Francisco lawyers.

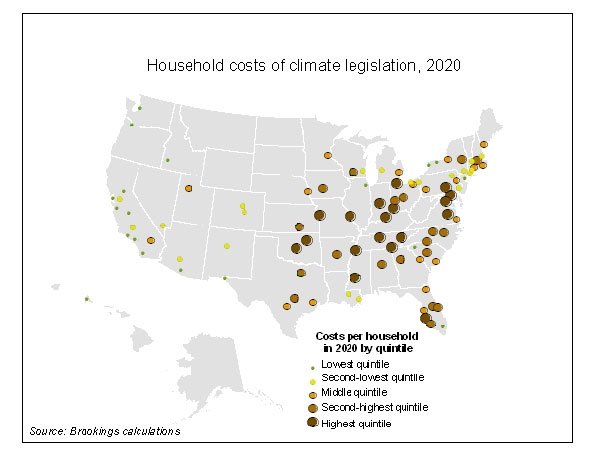

The Brookings Institution recently calculated the projected cost of compliance under the cap and trade plan on a metro by metro basis and produced the map below for The New Republic:

The costs of compliance are highest in the lower Midwest through to the Mid-Atlantic and in the South. New England, the Upper Midwest, and the West are the winners from a cost standpoint.

The actual costs vary from a high of $277 per household per year in 2020 in Lexington, KY to a low of $96 in Los Angeles among the 100 largest metros. Other hard hit metros include Washington, DC ($250), Indianapolis ($246) and Kansas City ($228). Among the winners are Portland ($107), San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont ($119) and Chicago ($135).

In aggregate, this adds up to a significant amount of money. The Cincinnati metro had 815,000 households in 2008. Brookings did not include their household estimates for 2020, but even with no population growth at all, at $244 per household that still adds up to about $200 million per year in compliance costs. To put that in perspective, Cincinnati is proposing to construct a new downtown streetcar system for that same amount of money. It could conceivably build a new streetcar line every single year in perpetuity for the cost of compliance. Portland has 835,000 households, for an annual compliance cost of $90 million. Though they are about the same size regions, Cincinnati will be paying over $100 million more per year compliance costs. This creates a $100 million disincentive to live or locate a business in Cincinnati vs. Portland.

In short, cap and trade creates disparities between metros. As the New Republic put it, “place matters” on cap and trade. And because the effects are geographically clustered, these disparities aren’t just local, they are regional. This is enough to immediately prompt the question as to whether or not this was an implicit design goal of the system.

Among the biggest beneficiaries of cap and trade is California. Its large metros are clustered together at the bottom of the list. I noted previously how California is placing a huge bet on the green economy as its engine of economy renewal. In fact, beyond legacy industries such as high tech, agriculture, and entertainment, California’s political leaders are betting their entire future on green. With so much on the line for California, it should come as no surprise that the state would seek to federalize its policies and institutionalize the advantages it has in this arena through its state level climate regulations. One might even better name this bill “The California Economic Recovery and Competitor Hobbling Act of 2009”.

This reality isn’t lost on Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels. With Indianapolis the fifth hardest hit metro in the country, it is no surprise he denounced the plan in a Wall Street Journal editorial, saying, “Quite simply, it looks like imperialism. This bill would impose enormous taxes and restrictions on free commerce by wealthy but faltering powers – California, Massachusetts and New York – seeking to exploit politically weaker colonies in order to prop up their own decaying economies.”

It is clear that getting a bill out of Washington is not just a matter of cost, but of states and regions jockeying for position. The significant regional disparities in impact grind the legislative gears and might ultimately imperil getting legislation passed. Reducing regional disparities could help improve the chances of action on carbon.

But shouldn’t places that implemented what is considered good policy be rewarded? To some extent, yes. Many places actually voted to cause economic pain for themselves for the sake of a better environment. Other places have fought environmental regulation every step of the way. Clearly, we do want to provide incentives for good behavior, and certainly not reward bad.

On the other hand, not all the differences in current carbon emissions or abilities to reduce them are the result of good policy. Quite a bit of them are the result of simple good luck. Some places have climates that reduce the need for heating and air conditioning. Other places face more extreme weather.

Plentiful clean energy sources are unequally spread throughout the country. Not every place has access to large amounts of solar, wind, or hydro power sources. Much of the Midwest and South built coal fired power plants due to plentiful coal supplies in the region. Technology and transportation costs made other sources cost prohibitive. Carbon emissions were not on anyone’s radar then. Some places like Chicago were fortunate to build nuclear plants, which were bitterly opposed by environmentalists at the time, but now are praised by some as a source of low carbon power.

In short, much of the inequality in carbon emissions results from accidents of geography or history, not deliberate bad choices. People shouldn’t be punished for practices that were rational at the times. As Saul Alinksy put it, “Judgment must be made in the context of the times in which the action occurred and not from any other chronological vantage point.” And while one could say perhaps regions whose climates require excessive heating and cooling shouldn’t be favored places to live, one could say the same about much of the West, including California, whose existence depends on a vast edifice of what many consider environmentally destructive water works.

To actually get action on carbon – the true imperative – we should adopt the following policy guiding principles:

- The goal is carbon reduction, full stop. Encumbering it with additional regional economic gamesmanship, or becoming overly enamored with particular means to that end should be avoided.

- Reducing carbon emissions will come with an economic cost. It isn’t realistic to expect that we will get away with pain free reductions. Obviously we should seek to get the best blend of costs and benefits, but let’s not pretend we can have our cake and eat it too, holding carbon action hostage to a standard that can never be met.

- The carbon reduction regime should not create significant regional cost disparities. As a purely practical matter, this helps ease passage and should be embraced. Complete equality is never realistic, but when some regions will pay twice as much as others, that by itself creates oppositional voting blocs. If a cap and trade scheme is the preferred approach, then perhaps assistance to high compliance cost areas should partially fund the transition away from coal and towards less polluting sources.

- The carbon reduction regime should not encourage business to migrate offshore. We should also not take action that reduces the attractiveness of America as a place to do business and especially to manufacture. Regulatory arbitrage already provides an incentive to move to China, where you can largely escape environmental rules, health and safety regulations, and avoid the presence of independent, vigorous unions. An ill chosen carbon regime could simply enhance China’s allure as a “carbon haven”. Again, this skews manufacturing regions and labor interests against action on carbon, while shifting production to areas with only minimal regulatory restraints.

In short, action on carbon reduction may well be a good policy goal. But we shouldn’t embrace any means to that end uncritically if it creates huge distortions in regional economic advantage or further damages America’s industrial competitiveness.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.

-

China’s Love Affair with Mobility

China Daily reports that car (light vehicle) sales reached 10.9 million units in the first 10 months of 2009, surpassing sales in the United States by 2.2 million. This was a 38% increase over the same period last year. Part of the increase is attributed to government programs to stimulate automobile sales.

China’s leading manufacturer is General Motors (GM), which experienced a 60% increase in sales compared to last year. By contrast, GM’s sales in the United States fell 33% in the first 10 months of the year on an annual basis. GM sold nearly 1.5 million cars in China, somewhat less than its 1.7 million sales over the same period in the United States.

-

Texas Dominates Milken’s New Best Performing Cities Index

Texas metropolitan regions hold down four of the top five and nine of the top 16 places in Milken’s new Best Performing Cities Index, released this morning. The rankings were authored by previous New Geography Contributor Ross DeVol, director of Regional Economics at Milken.

It’s refreshing to see a set of rankings attempting to take an objective, hard data-based look at comparative analysis. The Milken Rankings are a combination of job growth, wage and salary growth, high-tech GDP growth, and high-tech location quotients (see page 8 of the report).

A region’s industry mix plays a big role in its ranking; you can see energy-centric regions scoring well. But remember that these rankings also explicitly factor in high tech growth and high tech concentration.

Regions that avoided real estate inflation and those maintaining what they have or simply avoiding rapid decline tend to score better.

“‘Best performing’ sometimes means retaining what you have,” said DeVol. “In a period of recession, the index highlights metros that have adapted to weather the storm. As we move forward in a recovery that still lacks jobs, metros will be further tested in their ability to sustain themselves.”

The rankings include 324 regions, breaking them into two groups based on region size.

You can view the full lists at Milken’s interactive rankings website, and the full report includes analyses of the top large and small places.

Here’s the top and bottom 25 Large places:

Top 25 Large Regions Bottom 25 Large Regions 2009 rank 2008 rank Metropolitan area 2009 rank 2008 rank Metropolitan area 1 4 Austin-Round Rock, TX MSA 176 97 Bradenton-Sarasota-Venice, FL MSA 2 13 Killeen-Temple-Fort Hood, TX MSA 177 150 Birmingham-Hoover, AL MSA 3 3 Salt Lake City, UT MSA 178 144 Memphis, TN-MS-AR MSA 4 7 McAllen-Edinburg-Mission, TX MSA 179 117 Miami-Miami Beach-Kendall, FL MD 5 16 Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX MSA 180 120 Cape Coral-Fort Myers, FL MSA 6 21 Durham, NC MSA 181 183 Spartanburg, SC MSA 7 9 Olympia, WA MSA 182 178 Wilmington, DE-MD-NJ MD 8 5 Huntsville, AL MSA 183 189 Dayton, OH MSA 9 14 Lafayette, LA MSA 184 73 Merced, CA MSA 10 2 Raleigh-Cary, NC MSA 185 191 Hickory-Lenoir-Morganton, NC MSA 11 15 San Antonio, TX MSA 186 193 Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH MSA 12 29 Fort Worth-Arlington, TX MD 187 170 Providence-New Bed.-Fall Riv., RI-MA MSA 13 23 Dallas-Plano-Irving, TX MD 188 186 South Bend-Mishawaka, IN-MI MSA 14 37 El Paso, TX MSA 189 185 Kalamazoo-Portage, MI MSA 15 45 Wichita, KS MSA 190 197 Canton-Massillon, OH MSA 16 88 Corpus Christi, TX MSA 191 192 Ann Arbor, MI MSA 17 17 Seattle-Bellevue-Everett, WA MD 192 187 Atlantic City, NJ MSA 18 40 Baton Rouge, LA MSA 193 188 Youngstown-Warren-Board., OH-PA MSA 19 72 Tulsa, OK MSA 194 190 Grand Rapids-Wyoming, MI MSA 20 20 Greeley, CO MSA 195 196 Lansing-East Lansing, MI MSA 21 8 Tacoma, WA MD 196 199 Holland-Grand Haven, MI MSA 22 48 Fort Collins-Loveland, CO MSA 197 198 Warren-Troy-Farmington Hills, MI MD 23 54 Little Rock-N. Little Rock-Conway, AR MSA 198 194 Toledo, OH MSA 24 67 Shreveport-Bossier City, LA MSA 199 200 Detroit-Livonia-Dearborn, MI MD 25 41 Wash.-Arl.-Alex., DC-VA-MD-WV MD 200 195 Flint, MI MSA And the top and bottom 25 Small regions:

Top 25 Small Regions Bottom 25 Small Regions 2009 rank 2008 rank Metropolitan area 2009 rank 2008 rank Metropolitan area 1 1 Midland, TX MSA 100 110 Vineland-Millville-Bridgeton, NJ MSA 2 7 Longview, TX MSA 101 94 Parkersburg-Marietta-Vienna, WV-OH MSA 3 5 Grand Junction, CO MSA 102 114 Williamsport, PA MSA 4 26 Tyler, TX MSA 103 117 Mansfield, OH MSA 5 10 Odessa, TX MSA 104 85 Jackson, TN MSA 6 29 Kennewick-Pasco-Richland, WA MSA 105 115 Muncie, IN MSA 7 15 Bismarck, ND MSA 106 63 Flagstaff, AZ MSA 8 6 Warner Robins, GA MSA 107 112 Racine, WI MSA 9 11 Las Cruces, NM MSA 108 70 Dothan, AL MSA 10 17 Fargo, ND-MN MSA 109 105 Sheboygan, WI MSA 11 45 Pascagoula, MS MSA 110 97 Niles-Benton Harbor, MI MSA 12 23 Sioux Falls, SD MSA 111 100 Altoona, PA MSA 13 8 Bellingham, WA MSA 112 95 Terre Haute, IN MSA 14 38 College Station-Bryan, TX MSA 113 59 Redding, CA MSA 15 2 Coeur d’Alene, ID MSA 114 122 Lima, OH MSA 16 12 Cheyenne, WY MSA 115 75 Janesville, WI MSA 17 81 Texarkana, TX-Texarkana, AR MSA 116 96 Elkhart-Goshen, IN MSA 18 27 Waco, TX MSA 117 119 Anderson, SC MSA 19 16 Houma-Bayou Cane-Thibodaux, LA MSA 118 113 Dalton, GA MSA 20 44 Laredo, TX MSA 119 120 Springfield, OH MSA 21 40 Abilene, TX MSA 120 84 Lewiston-Auburn, ME MSA 22 25 Iowa City, IA MSA 121 116 Muskegon-Norton Shores, MI MSA 23 72 Glens Falls, NY MSA 122 121 Saginaw-Saginaw Township North, MI MSA 24 24 Billings, MT MSA 123 123 Battle Creek, MI MSA 25 64 Ithaca, NY MSA 124 124 Jackson, MI MSA -

Bowling Alone or Bowling Along?

It has long been cultural sport to mock or to misunderstand the social life of suburbs. More recently, however, sport itself has been identified as a major arena for social decline in suburbia.

In his Bowling Alone, published with an almost apocalyptic sense of timing at the beginning of the present century, the esteemed social scientist Robert Putnam focused upon the decline of the American bowling leagues as symptomatic of a lost America. League bowling took off during the fifties and peaked during the sixties before its decline set in after 1970. From this downward trajectory, Putnam widens his analysis to raise serious and important questions about the culture of civic engagement in the USA. In other works, Putnam has also viewed the localised politics of northern Italian towns in a more favourable light than the sprawling suburbs of the USA.

Putnam worries that both community involvement and church attendance is lower in the central cities and suburbs of major metropolitan areas than in the smaller towns of the USA of which he is clearly enamoured. He places this in the wider context of the more mobile, privatised and suburban way of life that has developed in America and other countries, including Britain, since the fifties. Somewhat ironically, perhaps, the decade that was once diagnosed as bringing about the Organisation Man and the Lonely Crowd of tract suburbia, is now viewed as a decade of suburban neighbourliness. What Putnam terms the ‘compulsive togetherness’ of the fifties has been eroded, apparently, by atomised isolation, self-interest and ever widening widths of commuting and social connectivity.

Yet Putnam’s own statistics do not support the widely cited assertion of declining suburban sociability as compared to urban centers. In his argument that “community involvement is lower in major metropolitan areas” we find from tables in Bowling Alone that in the central areas of cities with one million or more people, about 7 per cent had served in a local community group, and almost 9 percent had attended a public meeting on town or school affairs. In the suburbs of that same-sized metropolis, over 10 per cent had served in a local community group, and over 15 percent had attended a public meeting on town or school affairs.

In communities between 250,000 and 1 million people – quite a range of cities – again the suburbs manifest higher levels of civic engagement than the city centres. In the town of 50,000 to 250,000 however, we find a slightly more mixed picture: 14 percent living in central areas had served in a local community group compared to 13 percent in the suburbs. This is a paltry differential. However, whereas over 15 percent in central cities of this size had attended a public meeting on town or school affairs, it was over 20 percent in the suburbs, a much wider gap.

When Putnam analyzes church attendance, his findings tend to exonerate suburban living. In the ”major metropolitan area of more than 2 million”, the “non-central city” manifests higher levels of regular church attendance than the central city. Yet in smaller metropolitan areas and towns both central and non-central areas have almost identical levels of church attendance.

Surely this all raises a significant questions about the common notion that suburbanisation is bad for local community life. Of course, these figures may also be qualified by ethnicity, gender, occupational class and tenure. For example, home owners tend to be more rooted than renters, says Putnam. But most people living in the American suburbs are home owners, whereas rental levels are higher in downtown areas. Perhaps there is a weaker relationship between faith and tenure than between tenure and community participation?

So what about sports? Over time-spans of decades, people learn to like other sports, or new ones, and the younger generation does not always emulate the interests of its parents or grandparents. Interests and disposable income are shifted onto other pursuits. Baseball leagues and American football may be declining, but Putnam pays only lip service to the growing popularity of sports such as skating, snowboarding, fitness walking and going to the gym. These are sports that now bind young people together via discussion on social networks and in media like fuel.tv in terms of fashion and popular events.

For his part, Putnam sees these as symptomatic of a modest demise in team sports as more individualised pursuits become increasingly common. Yet he may be missing the social aspects of the new “extreme” sports.

He also seems oblivious to the growing social role of soccer, particularly in the suburbs. He gives it three mentions in Bowling Alone. Relative to other countries, soccer may be a relatively small team sport in the USA, encouraged by immigration from soccer-loving countries, and cheered on by the soccer moms of America. But more important is the expansion of amateur soccer which attracts more young people. I would argue that the relative vitality of local soccer leagues is more important than the success of the professional leagues. After all, the issue is grassroots, volunteer social interaction, not mass behavior.

Soccer was originally born in England, and remains a vital force of social cohesion, particularly in suburban working-class council estates. The Old Left thinkers, many of whom have embraced Putnam’s ideas remain woefully ignorant of the energy and diversity of working-class suburban life.

Soccer remains the working-class sport that has refused to die, even when the English working class has been diagnosed with terminal decline. Whether at grassroots amateur level, in the lower professional leagues, and in the glamorous world of the Premier League and international competitions, the game continues to draw people together in parks, at football stadiums, around their television sets, and in a million and more websites dedicated to the sport.

The internet brings people together not just across the world but also in a local context. Online communities, and formal and informal emailing, are mechanisms not of isolation but of interaction. For example, in some research I have been doing on a poor suburban council estate in Southern England, the local tenants’ groups have established and maintain websites. And local amateur soccer in the English provinces has no shortage of websites dedicated to the sport and the teams who play it. And poorer working class areas are currently viewed by politicians and cultural commentators as possessing historically low levels of social capital.

Ultimately, Putnam is saying little that is new. In both England and the United States of America writers, film directors and metropolitan journalists have long played the game of bashing the suburbs. This elitist lineage can be traced back from the late-Victorian Diary of a Nobody to the nobodies at The Office, and from Babbit to American Beauty. The message takes on different emphases and tones but at its heart is contempt or faux sympathy for the allegedly alienated and privatised suburbanite. Films such as Backfield in Motion or Bend it Like Beckham give us a different take, but they aren’t as widely popular as American Beauty. Why is that? Perhaps their message is too optimistic. The chattering classes continue to want to paint suburbs as bastions of privatism rather than as a flexible and sociable context for community and association. The fact that they are, on the whole, woefully wrong is likely not to change their opinions, but should inform those who have not yet closed their minds.

Mark Clapson is a social historian, with interests in suburbanisation and social change, new communities in England and the USA, and war and the built environment.