For the past decade a large coterie of pundits, prognosticators and their media camp followers have insisted that growth in America would be concentrated in places hip and cool, largely the bluish regions of the country.

Since the onset of the recession, which has hit many once-thriving Sun Belt hot spots, this chorus has grown bolder. The Wall Street Journal, for example, recently identified the “Next Youth-Magnet Cities” as drawn from the old “hip and cool” collection of yore: Seattle, Portland, Washington, New York and Austin, Texas.

It’s not just the young who will flock to the blue meccas, but money and business as well, according to the narrative. The future, the Atlantic assured its readers, did not belong to the rubes in the suburbs or Sun Belt, but to high-density, high-end places like New York, San Francisco and Boston.

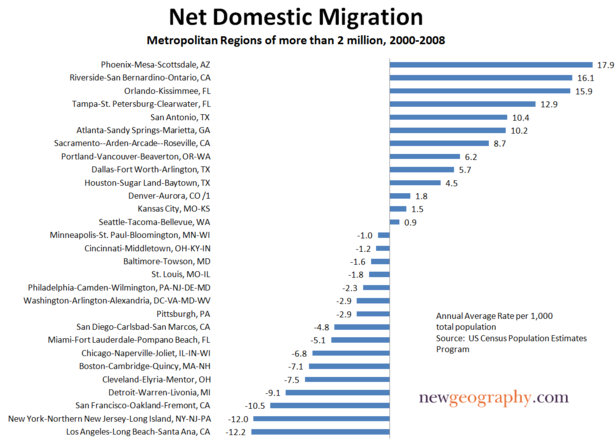

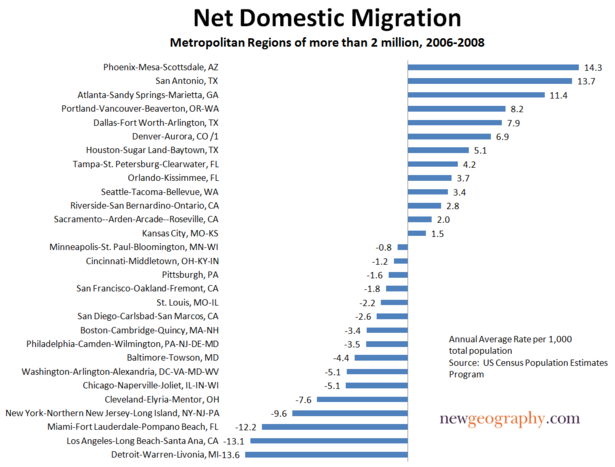

This narrative, which has not changed much over the past decade, is misleading and largely misstated. Net migration, both before and after the Great Recession, according to analysis by the Praxis Strategy Group, has continued to be strongest to the predominately red states of the South and Intermountain West.

This seems true even for those seeking high-end jobs. Between 2006 and 2008, the metropolitan areas that enjoyed the fastest percentage shift toward educated and professional workers and industries included nominally “unhip” places like Indianapolis, Charlotte, N.C., Memphis, Tenn., Salt Lake City, Jacksonville, Fla., Tampa, Fla., and Kansas City, Mo.

The overall migration numbers are even more revealing. As was the case for much of the past decade, the biggest gainers continue to include cities such as San Antonio, Dallas and Houston. Rather than being oases for migrants, some oft-cited magnets such as New York, Boston, Los Angeles and Chicago have all suffered considerable loss of population to other regions over the past year.

Much the same pattern emerges when you look at longer-term state demographic patterns. A recent survey by the Empire Center for New York State Policy found that the biggest net losers in terms of per capita outmigration between 2000 and 2008 were, with the exception of Louisiana, all blue state bastions. New York residents lead in terms of rate of exodus, closely followed by the District of Columbia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and California.

An even greater shock to the sensibilities of the insular, Manhattan-centric media, the report found that most of the movement from the Empire State was not from the much-dissed suburbia, but from that hip and cool paragon, New York City. This can not be ascribed as a loss of the unwanted: According to the report, those leaving the city had 13% higher incomes than those coming in.

How can this be, when everyone who’s smart and hip is headed to the Big Apple? This question was addressed in a report by the center-left, New York-based Center for an Urban Future. True, considerable numbers of young, educated people come to New York, but it turns out that many of them leave for the suburbs or other states as they reach their peak earning years.

Indeed, it’s astonishing given the many clear improvements in New York that more residents left the five boroughs for other locales in 2006, the peak of the last boom, than in 1993, when the city was in demonstrably worse shape. In 2006, the city had a net loss of 153,828 residents through domestic out-migration, compared to a decline of 141,047 in 1993, with every borough except Brooklyn experiencing a higher number of out-migrants in 2006.

Of course, blue state boosters can point out that the exodus has slowed with the recession, as opportunities have dried up elsewhere. True, the flood of migration has slowed across the nation. Yet it has only slowed, not dried up. When the economy revives, it’s likely to start flowing heavily again.

More important, the key group leaving New York and other so-called “youth-magnets” comprises the middle class, particularly families, critical to any long-term urban revival. This year’s Census shows that the number of single households in New York has reached record levels; in Manhattan, more than half of all households are singles. And the Urban Future report’s analysis found that even well-heeled Manhattanites with children tend to leave once they reach the age of 5 or above.

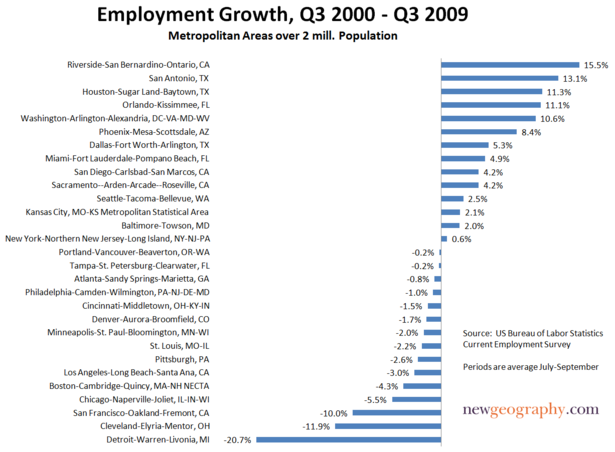

The key factor here may well be economic opportunity. Virtually all the supposedly top-ranked cities cited in this media narrative have suffered below-average job growth throughout the decade. Some, like Portland and New York, have added almost no new jobs; others like San Francisco, Boston and Chicago have actually lost positions over the past decade.

In contrast, even after the current doldrums, San Antonio, Orlando, Houston, Dallas and Phoenix all boast at least 5% more jobs now than a decade ago. Among the large-narrative magnet regions only one–government-bloated greater Washington–has enjoyed strong employment growth.

The impact of job growth on the middle class has been profound. New York City, for example, has the smallest share of middle-income families in the nation, according to a recent Brookings Institution study; its proportion of middle-income neighborhoods was smaller than that of any metropolitan area except Los Angeles.The same pattern has also emerged in what has become widely touted as America’s “model city”–President Obama’s adopted hometown of Chicago.

The likely reasons behind these troubling trends are things rarely discussed in “the narrative”–concerns like high costs, taxes and regulations making it tough on industries that employ the middle class. One clear culprit: out of control state spending. State spending in New York is second per capita in the nation (anomalous Alaska is first); California stands fourth and New Jersey seventh. Illinois is down the list but coming up fast. Over the past decade, while its population grew by only 7%, Illinois’ spending grew by an inflation-adjusted 39%.

The problem here is more than just too-large government; it lies in how states spend their money. Massive public spending increases over the past decade in California, New Jersey, Illinois and New York have gone overwhelmingly into the pockets and pensions of public employees. It certainly has not flowed into such basic infrastructure as roads, bridges and ports that are needed to keep key industries competitive.

The American Association of State Highway Transportation, for example, ranked New York 43rd in the country and New Jersey dead last in terms of quality of roads. Some 46% of the Garden State’s roads were rated in poor condition, compared with the national average of 13%, even as the state’s spending reached new highs. The typical New Jersey driver spends almost $600 a year in auto repairs necessitated by the poor conditions of the roads.

In contrast, states in the South and parts of the Plains tend to pour their public resources into productive uses. Cities like Mobile, Ala., Houston, Charleston, S.C., and Savannah, Ga., have been investing in port facilities to take advantage of the planned widening of the Panama Canal. The primary goal is to take business away from the increasingly expensive, overregulated and under-invested ports of the Northeast and West Coast. Similarly, places like Kansas City and the Dakotas are looking to boost their basic rail and road networks to support export-heavy industries.

Even in the face of the Obama administration’s strongly urban-centric, blue state-oriented economic policy, these generally less than hip places appear poised to grow as the economy recovers. Virtually all the top 10 economies that have withstood the recession come from outside the “youth-magnet” field: San Antonio; Oklahoma City; Little Rock, Ark.; Dallas, Baton Rouge, La.; Tulsa, Okla., Omaha, Neb.; Houston and El Paso, Texas. The one exception to this rule, Austin, also benefits from being located in solvent, generally low-tax Texas.

This continued erosion of jobs and the middle class from the blue states and cities is not inevitable. Many of these places enjoy enormous assets in terms of universities, strategic location, concentrations of talented workers and entrenched high-wage industries. But short of a massive and continuing bailout from Washington, the only way to reverse their decline will be a thorough reformation of their governmental structure and policies. No narrative, no matter how well spun, can make up for that reality.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.