Currently in the United States about 27% of all homes have some form of a home based business. These businesses can be key to conservation efforts that lower our carbon footprint by reducing transportation needs, eliminating redundant facilities, and consolidating equipment. They provide significant opportunities for two solutions to problems that face today’s growth issues.

My software company was founded in Dallas, where I worked from the dining room table in an apartment. I yearned for the day my business could operate out of a real office. After the business started generating a positive cash flow the apartment was left behind, and my office moved to a location in the newly built Dallas Galleria. My 104 square feet of office space was complimented with a separate meeting room, receptionist, and a parking space in the garage. All this cost me $600 a month. After the initial six month lease was up the rent skyrocketed and parking was no longer free; however, the 104 square feet remained the same.

Oh, how I yearned for a nice dining room table to work from!

Soon I decided that the money spent on rent — both apartment and Galleria office — could build a really nice home. In 1982 I built a home specifically designed for a residence and my business. With about 4,000 square feet, of which about one third was dedicated business space with a separate office entrance, we had a viable base from which to live and work.

The IRS allowed us to write-off one third of the total housing expenses without question. By not having to pay office rent we could double the home payments, and the 30 year mortgage was paid in full in less than 10 years.

Maple Grove, the lakefront suburban Minnesota community where we had built, allowed a home business occupation via ordinance limited to one non-family employee. At first we complied, but the business grew. At times there were up to 6 employees at the home, but neighbors did not complain.

I was not the only lake front home operating a big business. Across the lake, a major manufacturer of car radar warning units operated out of the basement of a house. This was a husband-and-wife business, but it was no small operation. The company had full page ads in leading automotive magazines. I sometimes visited; I’d hear the phone ring with an order, and the wife would say ‘I’ll see if we have any in stock at the warehouse, can you hold?’ She would then call down to the basement and ask if they could make an A-50 unit for shipping. Nobody but the UPS man would know the truth!

Solution #1: The Residential/Business

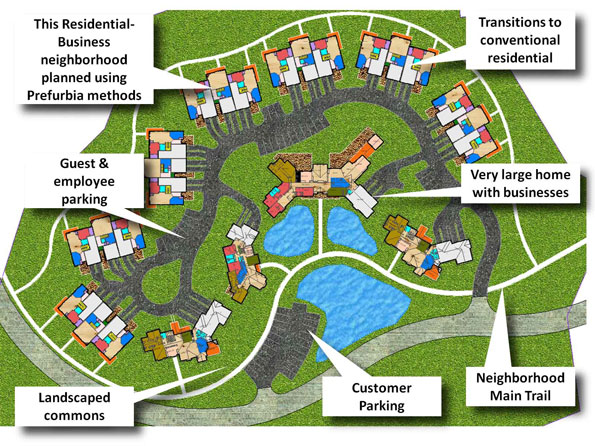

The Residential/Business (RB zoning) would be an entirely new land use, sort of a morphing of an office center and a neighborhood of luxury single family homes. Office complexes typically have a higher degree of landscaping and architectural detail than single family developments. In the RB neighborhood, homes would be large and impressive with heavily landscaped commons that serve as pedestrian access to the businesses that are located within the home structure.

Family members and employees would park in the rear, with multiple garage spaces and outside parking for the employees. From the arterial streets abutting these developments it would be an impressive sight, giving a sense of wealth to the neighborhood and municipality. The types of businesses would be restricted to low traffic professional services, including medical services, but also could include very light manufacturing. The RB zones would be an excellent transition (buffer) from commercial centers to residential ones. The RB residential structures would house the entire business and home, serving as the main hub for all of the business needs.

Below, a Residential/Business community

There could be some overlap of business functions into the residential elements of the home. For example, a conference center with an 80 inch screen for presentations could be used for Monday night football on occasion. From a financial standpoint, for a small to medium sized business owner this is a win-win situation. It delivers the advantages that I had experienced in my own situation in a comprehensive, specifically designed development plan.

Solution #2: The Cyber Village

George E. Van Hoesen, of Global Green Building, LLC, has developed an alternative solution, the Cyber Village.

The proliferation of computers and cell phones, as well as video conferencing and express delivery, has made the notion of the at-home cyber office an excellent solution for growth issues. New definitions of work, recreation, and education have brought the family home again. Residential design and community planning can begin to address the increasing needs of these new households while keeping the neighborhood’s primarily residential character.

Unlike the Residential/Business solution, homes in the Cyber Village need not be as business intensive or change the character of a neighborhood. A main component of the Cyber Village is the Cyber Office, serving as the community foundation for business activity. This facility, complete with offices, reception services, mail services, meeting rooms, board rooms, reference libraries and office equipment, would serve subscribers (businesses within the neighborhood) for their out-of-office and administrative needs. This Cyber Office location could serve as the hub for deliveries, recycling, storm shelter, resource center, rideshare, and other community resource needs. Subscribers would choose the level of access to the facility based on their own individual business needs. The features of the cyber office would lend credibility and added professionalism to a residence-based business without breaking the bank.

Below, a Cyber Village

The neighborhood Cyber Office could be managed as a for-profit business, providing services for a fee. Communities could also manage a Cyber Office as a part of the homeowners association. A mix of services could be provided, depending on the needs of the community. The overall concept reduces the carbon footprint of the home-based business and addresses the needs of the changing work place.

Zoning Both Solutions

Both solutions fall outside the scope of conventional zoning. The Cyber Village may comply more easily with existing regulations, especially those that allow a home to operate a business with a few employees. If a city’s regulations are flexible enough, it may be possible to design and implement a Cyber Village that complies with city code now. The Residential/Business solution, with its more aggressive business size, would compete with — or make obsolete — office complexes. Office “use” is often taxed at a higher rate than residential use. Since cities do not like to lose tax revenue, it is likely that municipalities would require a new basis to tax the RB residents.

Creating a new zoning class and tax classification is not difficult, but it might be time consuming. The current slow market allows cities to restructure their zoning and tax codes, so now is the time to act.

Both solutions would have a significant reduction on the carbon footprint of land development. They offer alternatives to the Smart Growth solutions in which shop owners are encouraged to live over their stores in high density developments. Both the Residential/Business and the Cyber Village alternatives curb traffic and sprawl…and at the same time, provide residential settings with enough space for family enjoyment.

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable. His website is rhsdplanning.com.