“‘There is no question that her willingness and ability to use social network media, including the latest flap on her [pictures] on Twitter, makes her much more credible and accessible to the Millennial Generation,’ says Morley Winograd, a fellow at the think tank NDN and co-author of ‘Millenial Makeover: MySpace, YouTube and the Future of American Politics.’”

Blog

-

Stimulate Yourself!

Beltway politicians and economists can argue themselves silly about the impact of the Obama administration’s stimulus program, but outside the beltway the discussion is largely over. On the local level–particularly outside the heavily politicized big cities–the consensus seems to be that the stimulus has changed little–if anything.

Recently, I met with a couple of dozen mayors and city officials in Kentucky to discuss economic growth. The mayors spoke of their initiatives and ideas, yet hardly anyone mentioned the stimulus.

“We didn’t see much of anything,” noted Elaine Walker, mayor of Bowling Green, a relatively prosperous town of 55,000 in the western part of the state. “The money went to the state and was siphoned off by them. We got about zero from it.”

Ironically, Walker does not seem overly upset about the lack of federal assistance for Bowling Green. Instead, Walker–a self-described supporter of the president in a part of the country largely resistant to Obamamania–seems more disposed to taking matters into her own hands. Rather than waiting for Obama, Bowling Green is looking to stimulate itself–and other communities would do well to emulate this grassroots approach

Bowling Green’s “self-stimulation” is part of a concentrated effort at diversification for the city, which has long depended on its General Motors plant, which produces the Corvette. Other single-industry-dominated regions, notably Detroit, have made much noise about moving into other fields, but their emphasis has frequently revolved around high-profile, highly subsidized projects such as “green” industries, entertainment or tourism.

Instead, says Walker, the first step in diversification lies with boosting small local businesses.

A primary vehicle for this has been the successful Small Business Accelerator located at an abandoned mall. Buddy Steen, who runs the program in conjunction with Western Kentucky University, claims it has fostered some 38 companies and created over 700 jobs. Blu Pharmaceuticals, developed by Small Business Accelerator, for example, currently employs five but expects to add another 40 workers at its new plant in nearby Franklin. The program’s other firms specialize in everything from electronic warfare to robotics.

Kentucky may seem an unlikely spot for such ventures, admits local entrepreneur Ed Mills, but things are changing in the Bluegrass State. Mills, a former General Motors executive, and his twin sons, Clint and Chris, founded a Web-based software firm, HitCents, in 1995 when the boys were still in high school.

Today the company, which develops software for retail and other applications, has over 50 employees and customers from across the country, including GM, as well as a host of local companies, unions and public agencies. “We hope to build a $100 million company, and we think we can do it.” Mills says. “You don’t have to be in California. People think you can’t do this in Kentucky but plainly you can.”

With its strategic location on Interstate 65 connecting the old industrial heartland to the emerging one along the Gulf, Bowling Green enjoys many advantages. It’s slightly over an hour to Nashville and two hours to Louisville, the area’s two major consumer and cultural marketplaces.

Other small communities in the state have also realized that any green shoots would have to come from local grassroots. Russellville, a rural community of some 7,200 in the southwest part of the state, is looking at a “back to basics” economic development plan that stresses the export of local food products and crafts.

“You can ride down the highways and smell the hams smoking,” notes one local economic developer. “We are looking on how to export those hams to the rest of country.”

Mayor Gary Williamson of Mt. Sterling, a town of 6,000 located in Montgomery County, in the generally more impoverished east, has been pushing a different strategy. His region is dotted with industrial plants of varying sizes. The city is also 45 minutes from Georgetown, site of a large

Toyota factory.These employers require a steady stream of skilled industrial workers, particularly in such fields as machine maintenance. Williamson and other officials in the area see training such workers–starting at the high school level–as a way to not only keep people employed but to attract other firms to the area. “We want to keep people here, and they will do so if they have jobs after school,” he explains.

It’s significant that such grassroots-based development–geared to unique local conditions–is taking place in Kentucky. For generations, the state and the rest of the surrounding Appalachian region has been the brunt of both jokes and patronizing attention from the nation’s academes, policy circles and media.

Most Americans, observed Newsweek in 2008, “see Appalachia through the twin stereotypes of tragedy (miners buried alive) and farce (Jed Clampett).” One prime reflection of that approach can be seen in a CNN report last year that painted a decidedly dismal portrait of the region.

For generations, Appalachia’s seeming backwardness has led to the creation of numerous federal programs aimed at lifting it into the national economic and cultural mainstream, notes University of Kentucky historian Ronald Eller. In his excellent Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945, Eller describes how these efforts reflected the region’s “struggle with modernity.” Progress has been often associated with efforts to undermine what the late Michael Harrington described as a “separate culture, another nation with its own way of life.”

Yet, this unique culture also could provide some of the basis for a regional recovery. There’s a growing sense, notes longtime Kentucky League of Cities President Sylvia Lovely, that the region’s fundamental assets–its natural beauty, resources and traditions of craftsmanship–could constitute a distinct advantage in the coming decades.

More important still could be less tangible values, Lovely notes. “Modernity” in its current unadulterated form–with a lack of community, homogeneity and disconnect from the natural world–could be losing its allure for millions of Americans. In terms of what matters, she suggests, Appalachian towns may possess “if not more information, perhaps more wisdom than those who hold themselves out as experts. “

Looking at the statistics, the news is not all grim. Despite its still glaring problems, particularly in its rural hinterland, Appalachia has been gaining steadily compared to the rest of the country. In 1960 one-third of Appalachia residents lived in poverty, compared with 1 in 5 nationally; by 2000 the poverty rates had fallen to 13.6%, just a tick higher than the national 12.3%. The region’s continued struggle with the gap between rich and poor, Eller notes, now more reflects broader national trends as opposed to something unique to the region.

Perhaps the most dramatic changes are illustrated by migration patterns. By the end of the 1960s one out of every three industrial workers in Ohio came from Appalachia. Young people studied, notes Eller, “reading, writing and Route 23,” referring to the main highway to the industrial north.

Since 2000 Kentucky, as well as Tennessee and West Virginia, have enjoyed positive rates of net migration. Although some parts of the region continue to suffer horrendous poverty and continued out-migration, many other communities–such as Bowling Green, Lexington and Louisville, as well some more rural areas–have attracted more newcomers than they have lost. Overall Appalachian states’ migration statistics look a lot healthier than Ohio and Illinois, not to mention New York or California.

Walker–who moved to Kentucky from Los Angeles shortly after the 1992 race riots–sees this new migration as part of what will sustain a recovery in the region. Like many newcomers, Walker came to Kentucky not for bright lights but for a good place to raise her children. “Everyone still waves and says hi,” she observes. “That makes a lot more difference to people than many think. In the end, people come here because it’s a better place to live and also to raise your kids. It’s all about families.”

Ultimately, a combination of folksiness and access to the world brought by technology could spark a continued renaissance not only in Bowling Green but across the region. The fact that the resurgence seems to be the product of largely local efforts not only makes it all the sweeter, but could inspire similar approaches among those communities still waiting for Washington to rescue them.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History

. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.

Downtown Bowling Green photo courtesy of OPMaster

-

The White City

Among the media, academia and within planning circles, there’s a generally standing answer to the question of what cities are the best, the most progressive and best role models for small and mid-sized cities. The standard list includes Portland, Seattle, Austin, Minneapolis, and Denver. In particular, Portland is held up as a paradigm, with its urban growth boundary, extensive transit system, excellent cycling culture, and a pro-density policy. These cities are frequently contrasted with those of the Rust Belt and South, which are found wanting, often even by locals, as “cool” urban places.

But look closely at these exemplars and a curious fact emerges. If you take away the dominant Tier One cities like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles you will find that the “progressive” cities aren’t red or blue, but another color entirely: white.

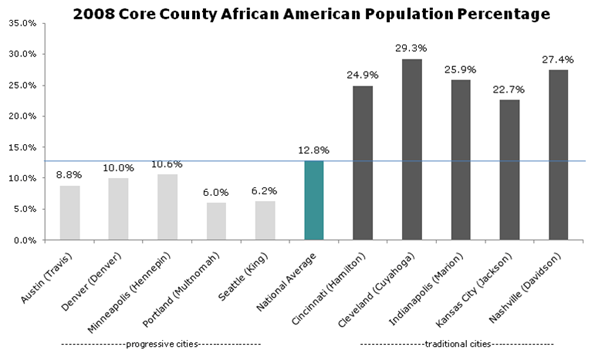

In fact, not one of these “progressive” cities even reaches the national average for African American percentage population in its core county. Perhaps not progressiveness but whiteness is the defining characteristic of the group.

The progressive paragon of Portland is the whitest on the list, with an African American population less than half the national average. It is America’s ultimate White City. The contrast with other, supposedly less advanced cities is stark.

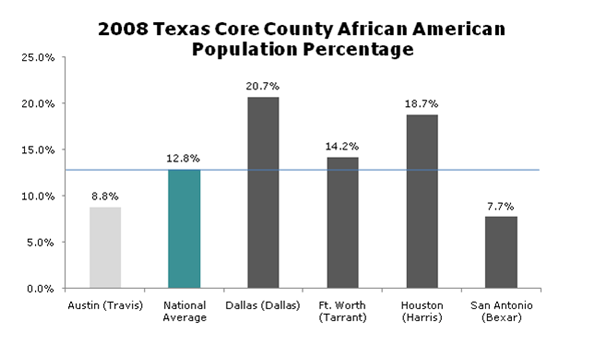

It is not just a regional thing, either. Even look just within the state of Texas, where Austin is held up as a bastion of right thinking urbanism next to sprawlvilles like Dallas-Ft. Worth and Houston.

Again, we see that Austin is far whiter than either Dallas-Ft. Worth or Houston.

This raises troubling questions about these cities. Why is it that progressivism in smaller metros is so often associated with low numbers of African Americans? Can you have a progressive city properly so-called with only a disproportionate handful of African Americans in it? In addition, why has no one called these cities on it?

As the college educated flock to these progressive El Dorados, many factors are cited as reasons: transit systems, density, bike lanes, walkable communities, robust art and cultural scenes. But another way to look at it is simply as White Flight writ large. Why move to the suburbs of your stodgy Midwest city to escape African Americans and get criticized for it when you can move to Portland and actually be praised as progressive, urban and hip? Many of the policies of Portland are not that dissimilar from those of upscale suburbs in their effects. Urban growth boundaries and other mechanisms raise land prices and render housing less affordable exactly the same as large lot zoning and building codes that mandate brick and other expensive materials do. They both contribute to reducing housing affordability for historically disadvantaged communities. Just like the most exclusive suburbs.

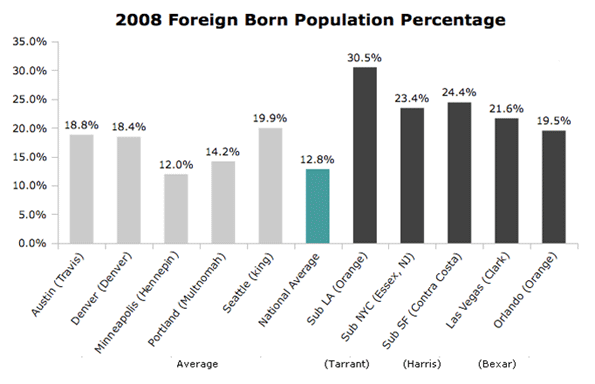

This lack of racial diversity helps explain why urban boosters focus increasingly on international immigration as a diversity measure. Minneapolis, Portland and Austin do have more foreign born than African Americans, and do better than Rust Belt cities on that metric, but that’s a low hurdle to jump. They lack the diversity of a Miami, Houston, Los Angeles or a host of other unheralded towns from the Texas border to Las Vegas and Orlando. They even have far fewer foreign born residents than many suburban counties of America’s major cities.

The relative lack of diversity in places like Portland raises some tough questions the perennially PC urban boosters might not want to answer. For example, how can a city define itself as diverse or progressive while lacking in African Americans, the traditional sine qua non of diversity, and often in immigrants as well?

Imagine a large corporation with a workforce whose African American percentage far lagged its industry peers, sans any apparent concern, and without a credible action plan to remediate it. Would such a corporation be viewed as a progressive firm and employer? The answer is obvious. Yet the same situation in major cities yields a different answer. Curious.

In fact, lack of ethnic diversity may have much to do with what allows these places to be “progressive”. It’s easy to have Scandinavian policies if you have Scandinavian demographics. Minneapolis-St. Paul, of course, is notable in its Scandinavian heritage; Seattle and Portland received much of their initial migrants from the northern tier of America, which has always been heavily Germanic and Scandinavian.

In comparison to the great cities of the Rust Belt, the Northeast, California and Texas, these cities have relatively homogenous populations. Lack of diversity in culture makes it far easier to implement “progressive” policies that cater to populations with similar values; much the same can be seen in such celebrated urban model cultures in the Netherlands and Scandinavia. Their relative wealth also leads to a natural adoption of the default strategy of the upscale suburb: the nicest stuff for the people with the most money. It is much more difficult when you have more racially and economically diverse populations with different needs, interests, and desires to reconcile.

In contrast, the starker part of racial history in America has been one of the defining elements of the history of the cities of the Northeast, Midwest, and South. Slavery and Jim Crow led to the Great Migration to the industrial North, which broke the old ethnic machine urban consensus there. Civil rights struggles, fair housing, affirmative action, school integration and busing, riots, red lining, block busting, public housing, the emergence of black political leaders – especially mayors – prompted white flight and the associated disinvestment, leading to the decline of urban schools and neighborhoods.

There’s a long, depressing history here.

In Texas, California, and south Florida a somewhat similar, if less stark, pattern has occurred with largely Latino immigration. This can be seen in the evolution of Miami, Los Angeles, and increasingly Houston, San Antonio and Dallas. Just like African-Americans, Latino immigrants also are disproportionately poor and often have different site priorities and sensibilities than upscale whites.

This may explain why most of the smaller cities of the Midwest and South have not proven amenable to replicating the policies of Portland. Most Midwest advocates of, for example, rail transit, have tried to simply transplant the Portland solution to their city without thinking about the local context in terms of system goals and design, and how to sell it. Civic leaders in city after city duly make their pilgrimage to Denver or Portland to check out shiny new transit systems, but the resulting videos of smiling yuppies and happy hipsters are not likely to impress anyone over at the local NAACP or in the barrios.

We are seeing this script played out in Cincinnati presently, where an odd coalition of African Americans and anti-tax Republicans has formed to try to stop a streetcar system. Streetcar advocates imported Portland’s solution and arguments to Cincinnati without thinking hard enough to make the case for how it would benefit the whole community.

That’s not to let these other cities off the hook. Most of them have let their urban cores decay. Almost without exception, they have done nothing to engage with their African American populations. If people really believe what they say about diversity being a source of strength, why not act like it? I believe that cities that start taking their African American and other minority communities seriously, seeing them as a pillar of civic growth, will reap big dividends and distinguish themselves in the marketplace.

This trail has been blazed not by the “progressive” paragons but by places like Atlanta, Dallas and Houston. Atlanta, long known as one of America’s premier African American cities, has boomed to become the capital of the New South. It should come as no surprise that good for African Americans has meant good for whites too. Similarly, Houston took in tens of thousands of mostly poor and overwhelmingly African American refugees from Hurricane Katrina. Houston, a booming metro and emerging world city, rolled out the welcome mat for them – and for Latinos, Asians and other newcomers. They see these people as possessing talent worth having.

This history and resulting political dynamic could not be more different from what happened in Portland and its “progressive” brethren. These cities have never been black, and may never be predominately Latino. Perhaps they cannot be blamed for this but they certainly should not be self-congratulatory about it or feel superior about the urban policies a lack of diversity has enabled.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.

-

The Compromise by the Lake

Toronto is a nice city.

If that seems like faint praise, then so be it; I’m not a great Toronto fan. Don’t get me wrong. It is a wonderful city for the tourist, and temporary residents I know swear by the place. But it’s not my kind of town.

I spent much time in Toronto in the 1980s and 90s. My first visit must have been in 1970 or so, and I was last there on a very cold, January day in 2003.

The city used to be known as “Tidy Toronto.” Indeed, that was the impression I got from my first visit – it all seemed very British, very clean, very orderly. In the 1970’s the Blue Laws were strict – it wasn’t possible to buy a cup of coffee on a Sunday morning. For the tourist (as I was then) it made for an unpleasant stay. These rules have weakened over the years, but as far as I know, many shopping malls and large stores are still closed on Sunday.

In contrast to the United States (Life, Liberty & the Pursuit of Happiness), Canada was founded as British North America on the principles of Good Government & Good Order. The Blue Laws are of a piece. There are some nice things about this: Canadian parks, including Toronto city parks, are much nicer and better maintained than their American counterparts. Toronto supports one of the largest public library systems in North America (an expensive anachronism?). They have street cars. The streets are (or at least were) cleaner. Canadian hotels and motels are fantastic – and apart from boring Sundays, Canada surely is one of the best countries in the world for the tourist. By all means, visit Toronto.

But compared to American cities of comparable size – Boston, Atlanta, Seattle – Toronto is stifling, provincial, and culturally unimportant. This, I believe, is why.

The city is situated on the northwest shore of Lake Ontario. The street system is oriented by the lake, which means E-W streets roughly parallel the shore. Thus, going east on Bloor will put you on a 75 degree heading. North-south streets are perpendicular – Yonge Street heads north at 345 degrees.

The lake is the city’s geographical feature of note, and serves as a transportation artery. Both the railroad and the Gardiner Expressway run right along the lakefront, thus cutting the city off from the water. City planners have tried mightily to rectify this fundamental error in design: they have built as many urban attractions as they can on the water side of the tracks, beginning with Queen’s Quay. This is nice enough, but is not easily accessible for pedestrians (one has to cross both the expressway and the tracks to get there). And then it is a synthetic cityscape, such as Manhattan’s South Street Seaport or Chicago’s Navy Pier: seen one, you’ve seen them all. Off shore are the Toronto Islands, now mostly used as park space. I’m ashamed to admit I’ve never been there.

I’ve always thought of the center of town being the corner of Yonge and Bloor Streets, for that surely is the busiest subway stop. It is an impressive corner, similar to Chicago’s Michigan Ave (though on a much smaller scale).

South of Bloor, Yonge Street is the city’s major promenade, where young people go to see and be seen. They strut by on wheels and on foot, in hot rods and hot clothes. It’s a great place to walk on a Summer evening.

A half mile (Toronto’s streets were designed long before Canada went metric) south of Bloor is Dundas Street, a street that doesn’t follow the grid (probably an old Indian trail). Yet another half mile south is Queen Street, the main E-W pedestrian thoroughfare and location of Eaton Centre – a huge, indoor shopping mall (apparently now open on Sunday). Further south are King Street, Front Street, Union Station, and then the Gardiner Expressway at the foot of Yonge Street. Yonge St. becomes less lively south of Queen St.

Walking west on Queen Street (highly recommended) one comes first to Nathan Phillips Square, location of the justly famous Toronto City Hall. The old city Hall, a beautiful red brick building to the east, is just as impressive. In the summer there are fountains, and in the winter ice skating. Beyond this is Osgood Hall, a judicial institution and a lovely building surrounded by a marvelous garden. Go inside if you can. En route you will cross Bay Street, Canada’s financial center. The heart of the financial district is Bay & King Streets.

Continuing west brings one to University Avenue, a broad, visually spectacular boulevard. It is full of institutions: Ontario Hydro has its headquarters here, as do large insurance companies. It is not a shopping street. About a mile north, University Ave. divides to surround Queen’s Park, the location of the Ontario Provincial Legislature. It is a beautiful park and an interesting building. “At Queen’s Park today,” begins many a news cast, “Premier McGuinty announced…” North of Queen’s Park, University Avenue turns into the redundantly named Avenue Road.

Continuing west on Queen brings one to Spadina Avenue, a major N-S traffic thoroughfare. Spadina and Dundas is the center of the traditional Chinatown. North of that, between Spadina and Queen’s Park, is the University of Toronto – the center of the campus is surrounded by King’s College Circle, and a pleasant walk.

Beyond Spadina, Queen Street is Toronto’s version of Greenwich Village, known as the Gallery District. Here are nice cafes, bookstores, small shops. I believe this used to be the center of the Italian district, and Italians still live on the West End and in Etobicoke. But West Queen St. has outgrown the ethnic identity.

Bathhurst, about a mile west of Spadina, forms the outer edge of the city center. Beyond this Queen Street looked like a slum, at least when I was last there.

East Queen Street, east of Jarvis, is skid row.

North of Bloor, between Yonge and Avenue Road, is an area called Yorktown – a mostly pedestrian area with narrow streets, small shops, and sidewalk cafes. Just to the east of Yorktown is Rosedale, a very elegant neighborhood of beautiful homes. Both are worth exploring on foot.

So that brings us back to the corner of Yonge & Bloor. Next time we’ll start again from there.

And what happens if you go east on Bloor?

Daniel Jelski is Dean of Science & Engineering State University of New York at New Paltz.

-

Wikigovernment: Crowd Sourcing Comes To City Hall

Understanding the potential role of social media such as blogs, twitter, Facebook, You Tube, and all the rest in local government begins with better understanding the democratic source of our mission of community service. The council-manager form of local government arose a century ago in response to the “shame of the cities” — the crisis of local government corruption and gross inefficiency.

Understanding what business we are in today is vital. It drives the choices we make and the tools we use. Railroads squandered their dominance in transportation because they defined their business as railroading. They shunned expansion into trucking, airlines, and airfreight. While they were loyal to one mode of transportation, their customers were not. Similarly, newspapers are in crisis because they defined their trade as the newspaper industry. Today’s readers don’t wait for timely news to arrive in their driveways. They have digital access on their computers and hand-held phones. Guess where advertisers are going?

Most local governments suffer similar myopia. Many managers define our core mission as delivering services. But that overlooks the history of why local governments deliver those services. We deliver police services in the way that we do because Sir Robert Peel invented that model in response to the public safety challenges of industrializing London.

We deliver library services because Ben Franklin invented that model in response to the need for working people in Philadelphia to pursue education and self-improvement. Governments didn’t arise to provide services; services arose from “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

Our core mission is not to provide traditional services, but to meet today’s community needs. To do this, we can learn more from the entrepreneurial risk-taking of Peel and Franklin than from public management textbooks.

We face these new dangers and opportunities:

• Transitioning from unsustainable consumption to living in sustainable balance with planetary resources.

• Overcoming an economic crisis that is slashing our capacity to maintain traditional services and meet growing community needs.

• Embracing growing diversity while dealing with increasing fragmentation marked by divergent expectations about the role of local government.During a similar period of historic upheaval, the young Karl Marx wrote that “all that is solid melts into air.”

Of course, it’s possible to underestimate the emerging crisis from the perspective of local government in many American towns and suburbs. The local voting population seems stable, though declining in numbers. The “usual suspects” still populate the sparse audiences at council and commission meetings. The budget is horrendous, but we’ve seen these cycles before.

In reality, this overhang is typical of the lag between action and reaction, the inertia Thomas Jefferson identified when he wrote, “Mankind are more inclined to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.”

In California, we’re confounded by the seemingly endless crisis in political leadership that is squandering our state’s credit rating and capacity to deliver vital services. Members of our political class resemble cartoon characters who dash off a cliff, then momentarily hang in the air before abruptly plunging. As the economist Herb Stein wryly observed, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

Global Communication Tools

In the current tough times, we all pay lip service to civic engagement and we all pursue it, with varying degrees of enthusiasm and success. But if we want to avoid plunging into the vortex like the state of California (and Vallejo, California, its bankrupt local counterpart), we will need to reassert and reinvent government of the people, by the people, and for the people in our communities.The textbook model puts the elected governing board squarely between us and the public. Elected officials interpret the will of the people. They’re accountable to the public. We report to those who have been elected. But in the modern world, professional staff cannot hide behind that insulation. We cling to the old paradigm because we lack a better one.

That’s where the real significance of social media comes into focus. These aren’t just toys, gizmos, or youthful fads. Social media are powerful global communication tools we can deploy to help rejuvenate civic engagement.

The Obama presidential campaign lifted the curtain on this potential. “Nothing can stand in the way of millions of people calling for change,” he asserted at a time when conventional political wisdom doubted his path to the White House. MyBarackObama.com wasn’t his only advantage, but he deployed it with stunning effectiveness to raise colossal sums from small donors, pinpoint volunteer efforts in 50 states to the exact places of maximum leverage, and carry his campaign through storms that would have capsized a conventional campaign.

It remains to be seen how this translates into governance at the federal level. But it has direct application to local democracy. Crowd sourcing is a new buzzword spawned by social media. It recognizes that useful ideas aren’t confined to positional leaders or experts. Wikipedia is a powerful success story, showing how millions of contributors can build a world-class institution, crushing every hierarchical rival. “Wikigovernment” is not going to suddenly usher in rankless democratic nirvana, but it’s closer to the ideal of government of the people, by the people, and for the people than a typical local government organization chart.

“To govern is to choose,” John Kennedy famously said. Choices must be made, and citizens will increasingly insist on participating in those decisions. As citizens everywhere balk at the cost of government, we can’t hunker down and wait for a recovery to rescue us. Like carmakers suddenly confronted by acres of unsold cars, we are arriving at the limits of the “we design ‘em, you buy ‘em” mentality.

A crowd-sourcing approach to local government resembles a barn raising more than a vending machine as a model for serving the community. Instead of elected leaders exclusively deciding the services to be offered and setting the (tax) price of the government vending machine, a barn raising tackles shared challenges through what former Indianapolis mayor Stephen Goldsmith calls “government by network.”

Citizen groups, individual volunteers, activists, nonprofits, other public agencies, businesses, and ad hoc coalitions contribute to the designing, delivering, and funding of public services. The media compatible with this model are not the newspapers such as — for example — the local newspaper that reports yesterday’s council meeting. The new media are the instant Facebook postings, tweets, and YouTube clips that keep our shifting body politic in touch.

The Dark Side

It’s not hard to conjure up the dark side of all this. Web presence is often cloaked in anonymity. This isn’t new in political discourse; the Founders engaged in anonymous pamphleteering. But the Web can harbor vitriol that wasn’t tolerated in the traditional press (at least until recently).The Web also tends to segregate people. One study concluded that 96 percent of cyber readers follow only the blogs they agree with. This self-selection of information bypasses editors trained in assessing the credibility of information. Opinion is routinely passed off as fact.

But it isn’t surprising that the cutting edge of digital communication is full of both danger and promise, nor should it keep us from using these new media in our 2,500-year quest for self-government. The atomization generated by a zillion websites also breeds a hunger for the community of shared experience. Both the election of Barack Obama and the death of Michael Jackson tapped into that yearning.

We can foster that yearning by deploying these exciting new tools in the service of building community. Yes, it’s risky to be a pioneer, but in a rapidly changing world, it’s even riskier to be left behind.

This is part two of a two-part series. A slightly different version of this article appeared in Public Management, the magazine of the International City/County Management Association; icma.org/pm.

Rick Cole is city manager of Ventura, California, and this year’s recipient of the Municipal Management Association of Southern California’s Excellence in Government Award. He can be reached at RCole@ci.ventura.ca.us

-

Commercial Real Estate Bust of 2010

Coming soon to a market near you: a bust in commercial real estate that will make the subprime mortgage crisis look like a picnic. The other shoe drops in 2010.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Chairman Sheila Bair told a Senate committee on October 14 that commercial real estate loan losses between now and the end of 2010 pose the most significant risk to U.S. financial institutions. Although you can’t read it online, on October 7, 2009 Wall Street Journal reporters Lingling Wei and Maurice Tamman (Eastern edition, pg. C.1, Fed Frets About Commercial Real Estate) reported on a presentation prepared by an Atlanta Fed real-estate expert who is worried “about the banking industry’s commercial real-estate exposure.”

Since July, the Federal Reserve has been pumping billions of dollars into commercial-mortgage-backed securities (CMBS, same things as the residential-MBS I’ve written about before in this space, only for shopping malls instead of houses). To accomplish this, the Fed uses the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility or TALF program. It is one of several alphabet-soup programs the Fed is using to pass a couple of trillion dollars to the stock market through private corporations (not just regulated banking institutions). For example, between March and July 2009, Harley-Davidson Inc. and other non-banks raised $65 billion in sales of bonds backed by everything from motorcycle loans to credit card debt. The Fed made $35 billion in TALF loans to investors buying those securities, which sparked a market rally. That market rally, however, is not in the commercial real estate market – it’s in the securities market. Since its inception, TALF has put between $2 billion and $11 billion per month into the securities market.

TALF lends money to anyone willing to buy CMBS (or student loans, car loans, etc.). The Fed reasons that, as long as banks can move loans off their books by repackaging and selling them as bonds, they will make more loans. So they justify giving money to non-banks to buy the bonds because the money will go to the banks. Get it?

Unfortunately, as vacancy rates rise, banks are increasingly reluctant to make new commercial real estate loans. This is obviously the case since Office of Thrift Supervision deputy director Timothy Ward told Congress this week that they will be issuing guidelines on doing loan workouts. A loan work out is what industry experts call “extend and pretend” – extend the terms and pretend like they are paying you. CRE loans, furthermore, are shorter in duration than home mortgages – typically 5 years instead of 30 years. That means a lot of loans will be coming due before the economy picks up enough to fill all those offices with rent-paying businesses. The value of commercial mortgages at least 60 days behind on payments jumped sevenfold in September – to $22.4 billion – or almost 4 percent of all commercial mortgages repackaged and sold as bonds. That’s about the same as the 90 day past-due rate seen for all residential mortgages (including those not sold off by the banks) in the first quarter of 2009.

As of October 14, 2009, the TALF balance is $43.2 billion and growing. From what we are hearing now, it may not be enough.

-

E-Government: City Management Faces Facebook

Does a City Manager belong on Facebook?

Erasmus, the Dutch theologian and scholar, in 1500 wrote, “In the country of the blind the one-eyed man is king.” I feel this way in the land of social media — at least among city and county managers. Inspired by the first city manager blog in the nation, started by Wally Bobkiewicz in Santa Paula, California, I began posting back in 2006. Although most bloggers strive for frequent, short blurbs, I’ve employed blogging to provide a place to get beyond the sound bites (and out of context quotes) in the local press. I seek to provide background, explanation, and context for the stories in the news, along with the trends that don’t make the news.

I tried MySpace and Facebook initially out of curiosity. For my first six months, I had only six friends on Facebook. Now I have more than 400, and few days go by when I don’t review requests for more. I post at least once a day, usually links to intriguing articles on public policy and photos of my three kids.

While I was finding my way as a boomer in cyberspace, I resisted Twitter…until an invitation arrived from a friend 30 years older than I. If someone in his 80s was interested in tweets from me, I figured the time had come to join the crowd. And although I’ve never made a YouTube video, several videos of me are floating in cyberspace.

For local managers, all of these social media offer new tools to work on one of democracy’s oldest challenges: promoting the common good. What local governments can’t do is fall hopelessly behind. The fate of railroads, automakers, and newspapers shows what happens to the complacent. It’s time to get online — and reach far beyond the initial step of a city website with links — to lead the effort to build stronger communities and a healthier democracy for the 21st century.

Civic Engagement and Social Media: The Ventura Case Study

Ventura has a civic engagement manager position, but civic engagement is considered a citywide core competency, like tech savvy and customer service. It’s not something we do periodically; it’s how we strive to do everything.

One of our key citywide performance measures is the level of volunteerism in the community. We look not just at the 40,000 volunteer hours logged by city government last year, but at the percentage of the population that volunteer for any cause or organization: 50 percent versus 26 percent nationally. We strive to raise awareness, commitment, and participation by citizens in local government and their community.

Reports by Council staff not only list fiscal impacts and alternatives, but document citizen outreach and involvement in each recommendation. There are obviously different levels; they recently ranged from a stakeholder committee that held four facilitated sessions to produce rules governing vacation rentals, to a citywide economic summit cosponsored with the chamber of commerce that drew 300 businesspeople and residents to develop 54 action steps unanimously endorsed by the city council at the conclusion.

Effective engagement requires aggressive, fine-tuned, and immediate communication. We address traditional media with a weekly interdepartmental round table that reviews what stories are likely to surface and identifies other stories we’d like to see covered. We encourage city staff to quickly post comments to online newspaper postings to set the record straight, respond to legitimate queries, and direct citizens to additional information on our website.

We have two public access channels — one for government, one for the community — and actively provide both with programming. Our most direct access comes from a biweekly e-newsletter that goes out to 5,000 addresses, linking directly to website resources, including the city manager’s latest blog post.

Slow at first to embrace Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, we’re closing the gap. One councilmember is a prolific blogger, and another uses Facebook for interactive community dialogue. We make judicious use of reverse 911 to get public safety information out quickly to residents. We’ve also pioneered “My Ventura Access”, a one-stop portal for all citizen questions, complaints, compliments, and opinions, whether they come by phone, Internet, mail, or in person.

Not Your Grandfather’s Democracy

Twitter, which allows just 140 characters – including spaces and punctuation – per “tweet”, gets a disproportionate share of the social media chatter. After a Republican member of Congress was ridiculed for tweeting during the State of the Union address this past February, Twitter usage exploded 3,700 percent in less than a year. By the time you read this, U.S. Twitter users will outnumber the population of Texas, or possibly California. In just five years, techcrunch.com reports, Facebook users have zoomed past 250 million. A Nielsen study estimates that usage has increased by seven times in the past year alone.

Yet as blogs, tweets, Facebook, YouTube, and text blasts reshape how America communicates, few local governments — and even fewer city and county managers — are keeping pace. E-government remains largely focused on websites and online services. This communication gap leaves local government vulnerable in a changing world. “Business as usual” is not a comforting crutch; it’s foolish complacency. Just look at the sudden implosion of General Motors, the Boston Globe, and the state of California.

It would be equally shortsighted to thoughtlessly embrace these new communication media as virtual substitutes for thoroughgoing civic engagement. We’re part of a 2,500-year-old experiment in local democracy, launched in Athens long before Twitter and YouTube. Local democracy operated long before the newspapers, broadcast media, public hearings, and community workshops familiar to today’s local government managers.

We may live in a hi-tech world, but the basis of what we do remains “high touch,” involving what some of the most thoughtful International City/County Management practitioners call “building community.” Social media offer new tools to build community, although they aren’t a magic shortcut.

This is part one of a two-part series. A slightly different version of this article appeared in Public Management, the magazine of the International City/County Management Association; icma.org/pm.

Rick Cole is city manager of Ventura, California, and this year’s recipient of the Municipal Management Association of Southern California’s Excellence in Government Award. He can be reached at RCole@ci.ventura.ca.us

-

American Agriculture’s Cornucopia of Opportunity and Responsibility

A complex agriculture, along with urban culture, is one of the fundamental pillars of human civilization, and one of the fundamental bulkwarks of American prosperity. For families and communities involved in farming and ranching it’s also a way of life that is cherished, oftentimes passed on through generations, taking on reverential if not religious overtones.

At the same time in today’s overwhelmingly urban culture, cooking has become prime time entertainment, dining a social event, and what a person eats is increasingly associated with a healthy body and mind – sometimes a sort of spiritual well being. This elevates agriculture to an important issue even among those who have never spent a day on a farm.

Sadly, recent years have seen mounting efforts to discount the value, in particular, of the industry’s productive core. A just published feature story in Time magazine – Getting Real About the High Price of Cheap Food – makes the following claim. “With the exhaustion of the soil, the impact of global warming and the inevitably rising price of oil — which will affect everything from fertilizer to supermarket electricity bills — our industrial style of food production will end sooner or later.”

Yet it is industrial, highly commercialized agriculture that first transformed America – and increasingly such countries as Australia, Brazil, Argentina and Canada – major forces in the world economy. The trend towards smaller-scale specialized production is indeed a welcome addition to our agricultural economy, but it is principally large-scale, scientifically advanced farming that produces the vast majority of the average family’s foodstuffs and accounts for all but a tiny percentage of our exports.

The attack on “industrial” agriculture reflects a growing trend by environmentalists to subordinate all productive industry to their own particular agenda. Some extremists in the local food movement would discourage cold climate inhabitants from the luxury of a midwinter tropical fruit because of the energy used in shipping. Others propose elaborate schemes for urban farming so that land can be left to nature instead of cultivation.

For others agriculture is guilty of producing a calorie-heavy, protein-rich diet that has made Americans unhealthy. In this lexicon ranchers, corn, and wheat farmers are not far removed from Afghan poppy growers or coca cultivators in South America.

The assault on agricultural production and the food system as we know it is certainly not limited to the United States. Farmers in Great Britain, where the often well-heeled advocates of bucolic romanticism hold great sway, have faced withering criticism. The National Farmers Union recently stated that the pressures on land use and practices could seriously damage the agricultural economy, with serious global and moral consequences.

Farming, they argue, depends “crucially on the productive core business remaining profitable. Without this core, British agriculture would “wither on the vine”, reducing both the global supply of food and making the UK ever more dependent on imports.

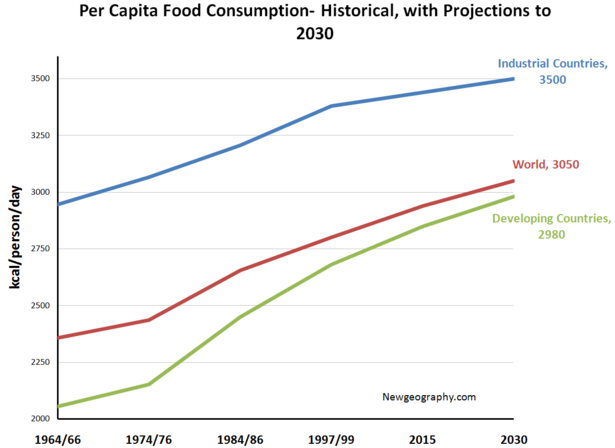

When applied to the United States, the world’s largest food exporter, the consequences could be devastating. By 2050 the population of the planet will reach around 9 billion people with more than 85 percent of the world’s population located in developing countries. Roughly half will live in developing-country cities. In the United States the population is expected to grow by another 100-milion people by 2050.

In this context, taking steps to reduce large-scale efficient production does not seem to be either a practical or humane choice. Certainly, better production and stewardship practices should be implemented and consumers can and could do more to drive these practices by making better nutritional decisions and choosing more responsible lifestyles.

But these concerns should not obscure the fact that American agriculture stands at the core of meeting the challenge of feeding the world’s expanding population. It does this not only by producing a staggeringly diverse array of crops with amazing efficiency, but also by leading the world in the export of the agricultural technology that helps other countries, notably in the developing world, feed their own people.

Greater Food Security and a Stronger Economy

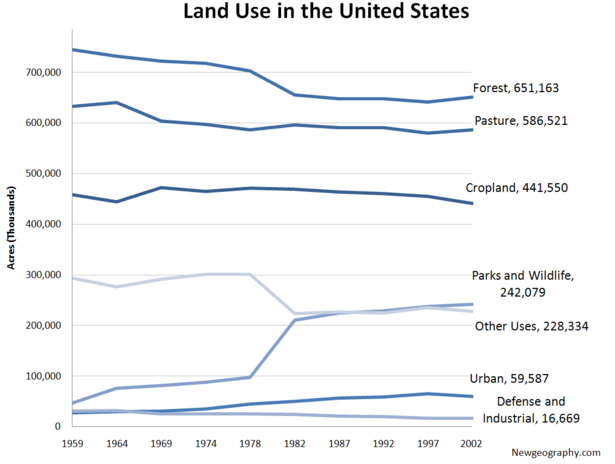

America’s agricultural producers have never been more productive and efficient than they are today. In 1953, the nation had a total of 5 million farms, working a total of 1.2 billion acres of land – the peak in production at that time. Over fifty years later, the number of farms in America has fallen by two-thirds, and the amount of land in use by producers has dropped by 25 percent, to around 900 million acres. Of the 2.2 million remaining farms, almost 96% are family owned. Even among the largest two percent of farms, 84% are family owned, challenging the commonly held perception of corporate domination.The US food industry is now the biggest in the world. In 2006, it was a $1.4 trillion sector, accounting for 12.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and 17 percent of the country’s workforce – the second largest U.S. employer behind government. In some regional economies such as the Midwest and Upper Great Plains the demand by farmers here, and now increasingly abroad, for sophisticated machinery and equipment has spawned entire new industry sectors in electronics, wireless networks, and new material fabrication. The continual demand for new and improved practices in both crop and livestock production and processing has created new opportunities in the life sciences and biotechnology.

This represents both an economic achievement and a great environmental benefit. Inputs of capital, labor, and materials have remained nearly steady, yet overall output has increased over two and one half fold over the same period of time. At the same time, efficient agriculture has returned to nature – forests, wetlands, prairie – millions of acres, far more than the land that has been devoted to housing and other urban needs.

Like successful industrialists, American farmers and ranchers have taken advantage of the latest advances in engineering, technology, and science to do more with less, creating “arguably the most productive, efficient, and technologically advanced production agriculture sector in the world”. Indeed as many American manufacturing industries have fallen behind their foreign competitors, agriculture has remained in the forefront, a bastion of American competitiveness.

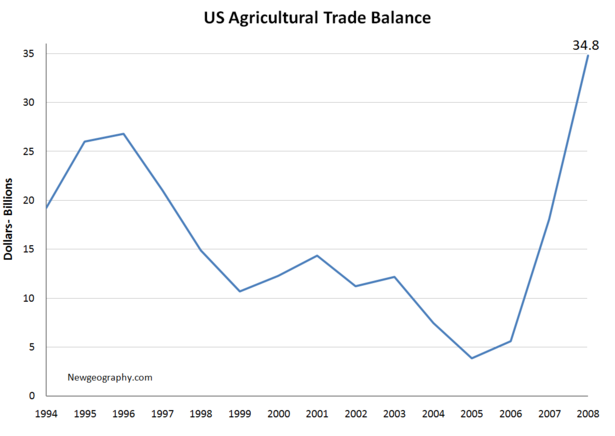

These increasing levels of productivity have allowed American agriculture to become a powerful player in world agricultural trade. As the nation has seen overall trade deficits mount to record levels in recent years, the agricultural sector has proven a notable exception. American farms, able to “produce far beyond domestic demand for many crops,” have looked to the world market to absorb their output. In 2008, the United States exported over $115 billion worth of agricultural products, a record high.

For the year, agricultural products made up ten percent of overall American exports, and the nation enjoyed an agricultural trade surplus of 35 billion dollars. While high commodity prices played their part in driving 2008’s export values higher, the agricultural sector has consistently shown export surpluses over the past 15 years, with the nation’s “share of the global market for agricultural goods,” averaging slightly over 20%.

On the domestic front, production agriculture – and the wider world of agribusiness – provides not only food, fuel, and fiber for Americans, but also a source of employment. Roughly 4.1 million people are directly employed in production agriculture as farmers, ranchers, and laborers; but up to 21 million Americans work in jobs that are tied in some way to agriculture –approximately one out of six participants in the U.S. workforce.

According to the USDA, the agricultural export industry supported as many as “841,000 full-time civilian jobs,” including “482,000 jobs in the nonfarm sector,” as of 2006. Production of food, fuel, and fiber involves support industries to supply the necessary inputs, and handle the product output, spurring economic activity in associated industries, including the “manufacturing, trade, and transportation sectors.”

The continual adoption of advanced technologies and methodologies by American farmers and ranchers also creates demand for advanced research and development activity, from both the public and private sectors.These, in turn, spawn educational and entrepreneurial opportunities in a multitude of scientific and engineering fields. USDA research suggests that “each dollar spent on agricultural research returned about $10 worth of benefits to the economy.”

Scaling Up Sustainable Agriculture

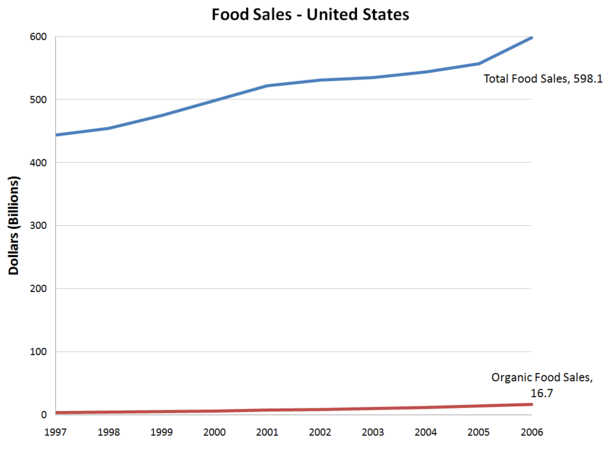

None of this suggests that there is not room as well for what is known as sustainable, usually smaller scale, agriculture. Organic agriculture, where farmers minimize external inputs and are not permitted to use artificial fertilizers, pesticides or herbicides, is the most widely recognized segment of the sustainable farming industry. U.S. sales of organic food and beverages have grown from $1 billion in 1990 to an estimated $20 billion in 2007, and are projected to reach nearly $23 billion in 2008.

This is clearly a growing industry, with organic food sales anticipated to increase an average of 18 percent each year from 2007 to 2010, according to an Organic Trade Association Manufacturing Survey. Yet organic foods and beverages account for less than 3 percent of all food sales in the United States – hardly enough supply or demand to feed a nation, much less a growing, hungry planet.

The same technology that drives commercial, large scale agriculture – and is largely paid for by its profits – could expand the role of this specialized sector. This includes a greater role for what is commonly called precision agriculture. With the aid of technologies such as global positioning (GPS), sensors, satellites or aerial images, and geographic information management tools (GIS), every input can be applied optimally to meet the exact needs of the crop, and can be tracked and tailored with precision. Precision agriculture can be used to reduce energy usage and environmental effects of production agriculture.

Precision agriculture builds on the strengths of America’s fundamental edge in innovation on the farm and in the factory. In the past, technology has been a major force in driving the shift of agricultural activities of the farm into the agribusiness input industries. Precision agriculture creates new and higher-value opportunities for agribusiness but also enables the farmer to apply the technology right in the field, thereby increasing the competitiveness and viability of farm operations of any size or ownership structure.

This suggests that there is, in many cases, a false dichotomy between industrial and sustainable agriculture. American agriculture now competes in a truly global marketplace with a cornucopia of opportunities that extend to both systems. Technology and a focus on productivity can help sustainable farming expand, but this should not be at the expense of the larger, commercial sector that not only funds most new research but will continue to play a dominant role in both feeding the world and sustaining that most endangered of species – the American economy.

Delore Zimmerman is the President of the Praxis Strategy Group an economic research and development strategy consulting company. Matthew Leiphon is a Research Associate with Praxis Strategy Group. Delore grew up in a small farming community in North Dakota, hauling bales and picking rocks for local farmers and ranchers. Matthew is from a North Dakota farm family and spends his fall weekends harvesting small grains and canola.