It was more than 45 years ago that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. enunciated his “Dream” to a huge throng on the Capitol Mall. There is no doubt that substantial progress toward ethnic equality has been achieved since that time, even to the point of having elected a Black US President.

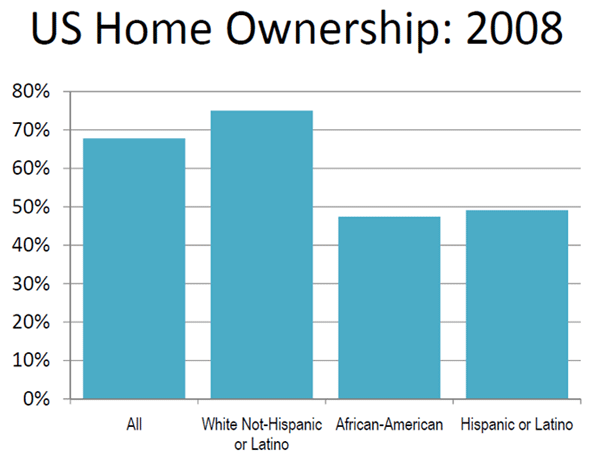

The Minority Home Ownership Gap: But there is some way to go. Home ownership represents the core of the “American Dream” that was certainly a part of Dr. King’s vision. Yet, there remain significant gap in homeownership by ethnicity. Rather than a matter of discrimination, this largely reflects differing income levels between White-Non-Hispanics, African-Americans and Hispanics or Latinos. Today, approximately 75% of white households own their own homes. Whites have a home ownership rate fully one-half higher than that of African-Americans and Hispanics or Latinos at 47% and 49% (See Figure).

Setting the Gap in Stone: A key to redressing this difficulty will be convergence of minority household incomes with those of whites, and that is surely likely to happen. However, there is another important dynamic in operation: house prices in some areas have risen well in advance of incomes, so that convergence alone can not narrow the home ownership gap in a corresponding manner. It is an outrage for public policy to force housing prices materially higher so long as home ownership remains beyond the incomes of so many, especially minorities.

The Problem: Land Use Regulation: The problem is land use regulation. The economic evidence is clear: more restrictive land use regulation raises house prices relative to household incomes. This can be seen with a vengeance in the house price increases that occurred during the housing bubble. As we have previously described, metropolitan markets with more restrictive land use regulation (principally the more radical “smart growth” policies) experienced house price escalation out of all proportion to other areas in the nation. In some cases, they topped out at nearly four times historical norms. On the other hand, in the one-half of major metropolitan area markets where land use regulations were less severe, house prices tended to increase to little more than historic norms, at the most.

How Smart Growth Destroys Housing Affordability: This difference is principally due to the price of land, which is forced upward when the amount of land available for building is artificially limited, as is the case in smart growth markets. At the peak of the bubble, there was comparatively little difference in house construction costs per square foot in either smart growth or less restrictive markets. However, the far higher land prices drove house prices in smart growth markets far above those in less restrictively regulated markets. Where house prices rise faster than incomes, housing affordability drops as prices rise at escalated rates.

Wishing Away Reality: It is not surprising that the proponents of smart growth undertake Herculean efforts to deflect attention away from this issue. Usually they pretend there is no problem. Sometimes they produce studies to indicate that limiting the supply of land and housing does not impact housing affordability, which is akin to arguing that the sun rises in the West. Even the proponents, however, cannot “walk a straight line” on this issue, noting in their most important advocacy piece (Costs of Sprawl – 2000) that their more important strategies have the potential to increase the cost of housing.

The Assault on Home Ownership: Worse, well connected Washington interest groups (such as the Moving Cooler coalition) and some members of Congress seek to universalize smart growth land rationing throughout the nation, which would cause massive supply problems and housing price inflation that occurred in some markets between 2000 and 2007. Even after the crash, these markets experienced generally higher house prices relative to incomes in smart growth markets than in traditionally regulated markets.

House Price Increases and Minorities: House price increases relative to incomes weigh most heavily on ethnic minority households, because their incomes tend to be lower. This is illustrated by an examination of the 2007 data from the American Community Survey, in our special report entitled US Metropolitan Area Housing Affordability Indicators by Ethnicity: 2007. The year 2007 was the peak of the housing bubble, but represents a useful point of reference for when future “smart growth” policies were imposed nationwide.

Median Priced Housing: The data (Table) indicates that median house prices were 75% or more higher for African-Americans than Whites, however that African-Americans in smart growth markets require 84% more to buy the median priced house. The situation was slightly better for Hispanics or Latinos with median house prices at least 50% more relative to incomes than for Whites. House prices relative to Hispanic or Latino median household incomes were 86% higher in smart growth markets than in less restrictively regulated markets.

| SUMMARY OF HOUSING INDICATORS BY | ||||

| LAND USE REGULATION CATEGORY | ||||

| Metropolitan Areas over 1,000,000 Population: 2007 | ||||

| HOUSING INDICATOR | Less Restrictive Land Use Regulation Markets | More Restrictive Land Use Regulation Markets | All Markets | More Restrictive Markets Compared to Less Restrictive Markets |

| MEDIAN VALUE MULTIPLE | ||||

| All | 3.1 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 1.89 |

| White Non-Hispanic or Latino | 2.7 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 1.90 |

| African-American | 4.9 | 8.9 | 6.9 | 1.84 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4.2 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 1.86 |

| LOWEST QUARTILE VALUE MULTIPLE | ||||

| All | 2.1 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 2.01 |

| White Non-Hispanic or Latino | 1.8 | 3.7 | 2.8 | 2.01 |

| African-American | 3.3 | 6.5 | 5.0 | 1.95 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2.9 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 1.98 |

| MEDIAN RENT/MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME | ||||

| All | 13.8% | 17.1% | 15.5% | 1.24 |

| White Non-Hispanic or Latino | 12.1% | 15.1% | 13.6% | 1.25 |

| African-American | 21.9% | 26.1% | 24.0% | 1.19 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 19.1% | 23.0% | 21.1% | 1.20 |

| LOWER QUARTILE RENT/MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME | ||||

| All | 10.8% | 13.1% | 12.0% | 1.22 |

| White Non-Hispanic or Latino | 9.4% | 11.6% | 10.5% | 1.23 |

| African-American | 17.0% | 20.0% | 18.5% | 1.17 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14.9% | 17.5% | 16.2% | 1.18 |

| NOTES | ||||

| Median Value Multiple: Median House Value divided by Median Household Income | ||||

| Low Quartile Value Multiple: Low Quartile House Value divided by Median Household Income | ||||

| 2007 Data | ||||

| Calculated from American Community Survey (US Bureau of the Census) Data | ||||

| “More restrictive” land use regulation markets (generally "smart growth") include those classified as "growth management," "growth control," "containment" and "contain-lite" and "exclusions: in "From Traditional to Reformed A Review of the Land Use Regulations in the Nation’s 50 largest Metropolitan Areas" (Brookings Institution, 2006) and markets with significant large lot zoning and land preservation restrictions (New York, Chicago, Hartford, Milwaukee, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and Virginia Beach). Less restrictive" land use regulation markets (generally "traditional") include all others, except for Memphis, where urban growth boundaries have been drawn far enough from the urban area to have no perceivable impact on land prices and Nashville, where the core county is exempt from the urban growth boundary requirement in state law. | ||||

Lower Priced Housing (Lowest Quartile): I recall being told by a participant at a University of California–Santa Barbara economic forum organized by newgeography.com contributor Bill Watkins that, yes, smart growth increases house prices, but not for lower income residents. My challenger went so far as to say that lower income households were aided economically by smart growth. The facts are precisely the opposite. Comparing the lowest quintile (lowest 25%) house price to median household incomes indicates that minorities pay even a higher portion of their incomes for lowest quintile priced houses than the median priced house. African-Americans in smart growth markets needed 95% more relative to incomes to afford the lowest quartile house. Hispanics or Latinos needed 98% more.

Rental Housing: The problem carries through to rental housing. There is a general relationship between rental prices and house prices, though rental prices tend to “lag” house price increases. In the smart growth markets, minorities must pay approximately 20% more of their income for the median contract rental in smart growth metropolitan areas than in less restrictively regulated markets. Similar results are obtained when comparing minority household median incomes with lowest quintile contract rents, with African-Americans paying 17% more of their incomes in smart growth markets and Hispanics or Latinos paying 18% more.

Moreover, it is important to recognize that all of the above data is relative, based on shares or percentages of incomes. Varying income levels are thus factored out. Minority and other households in smart growth markets face costs of living that are approximately 30% higher than in less restrictively regulated markets, according to analysis by US Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis economists. Some, but not all of the difference is in higher housing costs.

Social Costs of Smart Growth: In 2004, the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute, which focuses on Latino issues, noted concern about the homeownership gap in California, which has been ground zero for land use regulation driven house price increases for decades:

Whether the Latino homeownership gap can be closed, or projected demand for homeownership in 2020 be met, will depend not only on the growth of incomes and availability of mortgage money, but also on how decisively California moves to dismantle regulatory barriers that hinder the production of affordable housing. Far from helping, they are making it particularly difficult for Latino and African American households to own a home.

Examples of the restrictions cited by the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute are restrictions on the supply of land, high development impact fees and growth controls.

California has acted decisively, but against the interests of African-Americans and Hispanics or Latinos. The state enacted Senate Bill 375 in 2008, which will impose far stronger state regulations on residential development, increasing the likelihood that minorities in California will always be disadvantaged relative to White-Non-Hispanics. At the same time, State Attorney General Jerry Brown has forced some counties to adopt more restrictive land use regulations through legal actions. California, which had for decades been considered a state of opportunity, is making home ownership and the pursuit of the “American Dream” far more difficult, particularly for its ever more diverse population.

Stopping the Plague: In California, the hope to increase African-American and Latino home ownership rates to match those of white-non-Hispanics may already be beyond reach due to the that state’s every intensifying radical smart growth policies. However, the “Dream” continues to “hang on” in many metropolitan markets. Hopefully Washington will not put a barrier in the way of African-Americans and Hispanics or Latinos that live elsewhere in the nation.

US Metropolitan Area Housing Affordability Indicators by Ethnicity: 2007 includes tables with data for each major metropolitan area in the United States

Photo: Starter house in Atlanta suburbs (by the author)

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

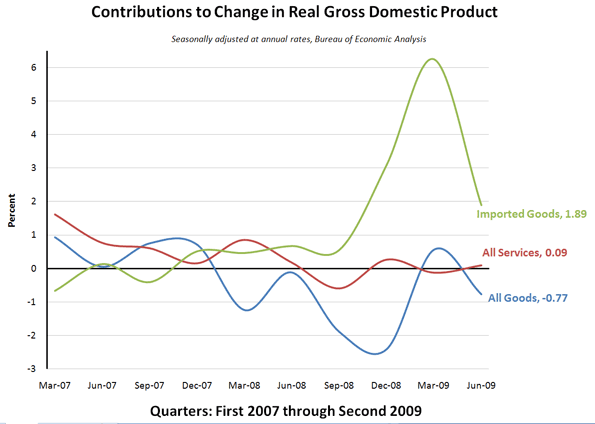

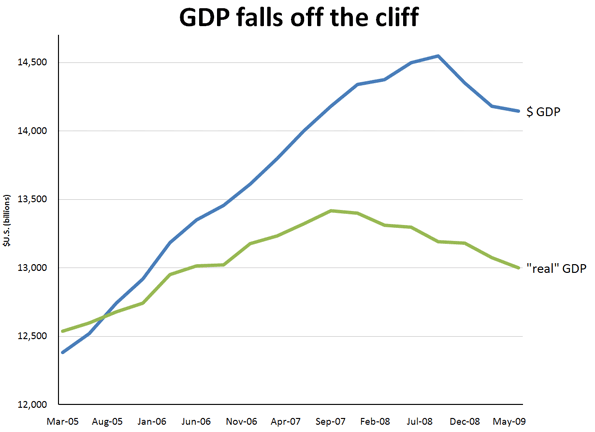

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations

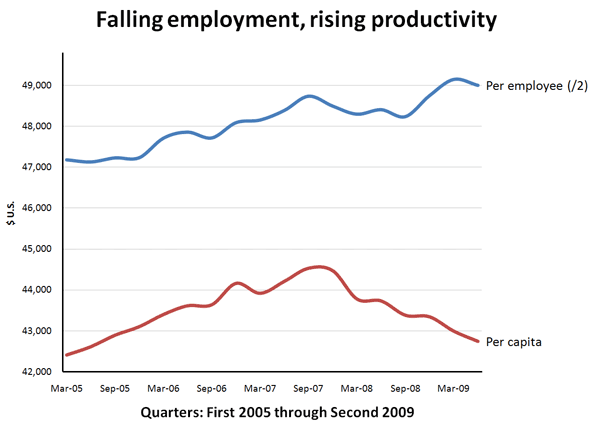

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Census Bureau. Per employee divided by 2 for scale.

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Census Bureau. Per employee divided by 2 for scale.