“Joel Kotkin, a weekly columnist for Forbes, wrotein theAugust 4thissue about why ‘Green Jobs Can’t Save the Economy.’ He reported, ‘Attempts to put windmills in Nantucket, Mass., the Catskills and Jones Beach in New York and other scenic areas have also been blocked by environmentalist groups. Transmission lines, necessary to take ‘renewable’ energy from distant locales to energy-hungry cities, often face similar hurdles. Solar farms in the Mojave desert might help meet renewable energy quotas but, as wildlife groups have noted, may not be so good for local fauna.’”

Blog

-

Contributing Editor MICHAEL LIND quoted on Later On regarding economic growth

“If you believe this theory, then Labor Day should be a cause for national mourning. We should all pause to mourn the loss of capital that might have gone to a fifth or a sixth mansion or a private jet, but instead was conscripted against its will to pay for a public school or higher wages in a factory.”

-

New Job Market Report from Jobbait Adds New Data

Mark Hovind over at Jobbait.com released his monthly job market report, and this month he’s expanded it significantly with sector-level data by state and metropolitan area.

Mark offers the numbers in an easily digestible format organized by state in color coded tables. It’s a great way to get a feel for what’s happening in your region or nationally.

Mark hopes this will help identify sectors with job prospects, even in regions where overall employment is declining.

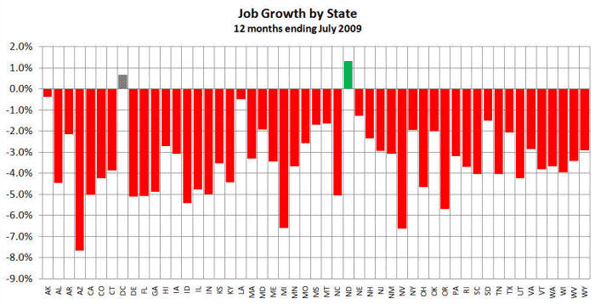

Looking at total job growth, North Dakota is still the only state showing year-over-year employment growth, followed by Washington, DC.

Fastest declining states by growth rate are Arizona, Michigan, Nevada and Oregon.

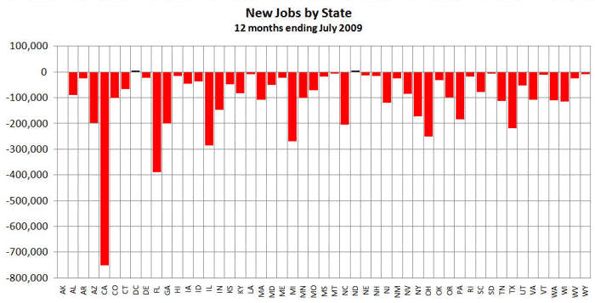

Fastest declining states by sheer numbers are California, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio and Texas.

See Jobbait.com for the full report.

-

Cookie Cutter Housing: Wrong Mix For Subdivisions

Nobody likes the taste of “cookie cutter” development. In the forty years that I’ve been in the land planning industry, at meeting after meeting I hear planning commissioners and city council members complain about the same thing: That developers submit the same recipes to cook up bland subdivisions over and over.

But while the developers are the scapegoat, it’s those who sit on the council and planning commissions that are as much, if not more to blame. They are also the ones with the power to change the status quo.

Communities have a cookbook that tells the developer and the design consultant the ingredients that must be used; this is called “The Ordinance”. Just as one might bake cookies using clearly defined amounts of flour and sugar, the cook looks to the ordinance to see that he will need exactly 10 feet between homes, at precisely a 20 foot setback from the curb, served up on a lot no greater than 5,600 square feet.

Thus, 100 cookies baked from the same recipe have about as much in common as the 100 lots built on “Pleasant Acres”. The developer presents the plan to the council. The scrumptious, pastel-colored rendering promises a tasteful development. But the council and planning members remember the aftertaste of the promises of past submittals.

Developers do not design land developments. They hire consultants who design them. The consultants are likely to be engineers and land surveyors, who also act as land planners. A cookie cutter development is called a “Subdivision”. A really large cookie-cutter development is called a “Master Planned Community”. In the end, no matter what its size, when you look down the street on which people live, both Subdivision and Master Planned Community have the exact same feel.

Why? Because the ordinance says so.

Yes, it’s true that the ordinance does not say anything about how to make creative, wonderful, sustainable communities; it only demands certain minimum dimensions and area restraints. But the key problem is that the developer, the engineer, the surveyor, and the planners think that the term “minimum” means the “absolute” dimensions.

So who cooked up these ordinances? Who determined that 5,600 square feet was the ideal lot size for the zoning in a particular city? Why does the fire department demand the public streets be 40 feet wide, when in a nearby city the public streets are just 26 feet wide? Are the buildings burning down over there, and not here?Citizens who have the power to create the changes that are needed – the councils, the planning commission members, and the Mayors — unquestionably embrace these recipes that enforce the absence of taste in their cities. Those who write regulations are actually often being paid to boilerplate these nauseating formulas from neighboring towns, when they should be looking to create entirely new recipes for tasteful development.

It’s time to throw out the systems that don’t work. Ordinances should be more reward-based and less minimum-based. A town’s regulations should ask developers to explain each element of the design and tell how it benefits the developer, the resident or business owner, and the city.

For example, most ordinances simply state: ’10 foot side yard minimum (20 feet between buildings)’. What if the ordinance was written as ’10 foot side yard’, then went on to explain that staggering the homes could offer a better streetscape. It might go on to mention that, with windows placed along the staggered side, living areas would have better views, making the homes more marketable. In this scenario, side yards could be reduced, to, say, 5 feet (10 feet between buildings). This type of regulation guides developers by rewarding better design with denser development. Virtually every aspect of the regulations could be written in such a manner. Nobody loses – everyone wins!

The developer’s consultants also deserve some of the blame. The developer will always hope for a project that will sell better than other developments in the area…always. Yet somehow, the developer trusts that the same consulting firm that designs all the other developments in town will have some special brainstorm that will somehow set this particular Subdivision apart.

This is one reason that nothing really changes. Another is that consultants who design Subdivisions (mostly licensed engineers and surveyors) are not likely to go against the rules. To a licensed individual who places his or her reputation and stamp on a plan, challenging a rule is very uncomfortable. Conflict between the consultant and the council and planning commission is highly feared: what if the change fails? The city’s representatives might view the consultant negatively on the next project. It’s far simpler to use one cup of flour and a tablespoon of sugar.

Until only six years ago I felt as if I was the only one challenging convention. At every meeting I would present plans that went beyond ordinance minimums to make sustainable and functional communities. At every meeting, typically in the back row, was the developer’s engineer, paid to attend. I had to defend against every question regarding engineering that was done outside of the recipe, and offer reasons for the benefits. Never once did an engineer who was paid to back me up offer support.

Then, in 2003 at a council meeting in the small town of Amery, Wisconsin, the impossible happened. On an engineering question, the developer’s consultant, Steve Sletner, owner of TEC Design, of Eau Claire, Wisconsin jumped right in and actually defended the changes we were challenging. A Licensed Civil Engineer became my instant hero (still is).

If every engineer thought more about the quality of life of those living in the developments that they engineer, this would be a much better world. Since then, Steve and I have been winning the war against the cookie-cutters in an enjoyable, relaxed atmosphere with councils and planning commissions everywhere.

Outside of the US, I’ve also found similar roadblocks to successful design. While in the Middle East, I met with the young head of sales for an extremely large developer. He complained about home designs that customers simply did not care for. I asked if he let his superiors know about the problems. Fear came across his face. Fear of confrontation is perhaps the biggest problem holding us back. Confrontation should not be an issue if there is supporting proof that the new solution offers less environmental impact and higher value, or is safer, etc.

An advantage we have in the US is that the citizens who sit on planning commissions and councils have more common sense than consultants give them credit for. When they don’t like the taste of what they are getting, they spit out negative comments at public meetings.

I wish that every planning commissioner and council member in this country could get this one message: If you don’t like the taste of what you are getting, hire a different cook to write a new cookbook for your community. President Obama recently stated that we must rely on the American spirit of innovation. A rewards-based regulatory system would be a major step in innovating the way our cities operate.

The planning industry needs a massive overhaul to replace our obsolete system with one that results in sustainable development. Minimum-based regulations are recipes that guarantee that only minimal cities will be built. Cities are the foundation of our society. And remember: You are what you eat.

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable. His website is rhsdplanning.com.

-

The Costs of Climate Change Strategies, Who Will Tell People?

Not for the first time, reality and politics may be on a collision course. This time it’s in respect to the costs of strategies intended to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Waxman-Markey “cap and trade” bill still awaits consideration by the US Senate, interest groups – mainly rapid transit, green groups and urban land owners – epitomized by the “Moving Cooler” coalition but they are already “low-balling” the costs of implementation.

But this approach belies a bigger consideration: Americans seem to have limits to how much they will pay for radical greenhouse emissions reduction schemes. According to a recent poll by Rasmussen, slightly more than one-third of respondents (who provided an answer) are willing to spend $100 or more per year to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. About 2 percent would spend more than $1,000. Those may sound like big numbers, but they are a pittance compared to what is likely to be required to meet the more than 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions that the Waxman-Markey bill would require. Even more worryingly for politicians relying on voters to return them to office, nearly two-thirds of the respondents would pay nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

If we do a rough, weighted average of the Rasmussen numbers, it appears that Americans are willing to spend about $100 per household per year (Note 1). This includes everyone, from the great majority, who would spend zero to the small percentage who would spend more than $1,000. At $100 per household, it appears that Americans are willing to spend on the order of $12 billion annually. This may look like a big number. But it is peanuts compared to market prices for greenhouse gas emissions. This is illustrated by the fact that the social engineers whose articles of faith requires building high speed rail to reduce greenhouse gas emissions would spend $12 billion to construct just 150 miles of California’s proposed 800 mile system.

Comparing Consumer Tolerance to Expected Costs: At $100 per household, Americans are prepared to pay just $2 per greenhouse gas ton removed. All of this is in a policy context in which the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggests that $20-$50 per greenhouse gas ton is the maximum that should be spent per ton. The often quoted McKinsey/Conference Board study says that huge reductions in greenhouse gas emissions can be achieved at $50 or less, with an average cost per ton of $17. International markets now value a ton of greenhouse gas emissions at around $20. At $2 per ton, American households are simply not on the same “planet” with the radical climate change lobby as to how much they wish to spend on reducing greenhouse gases.

International Comrades in Arms? This is not simply about Americans and their perceived differences from others who are so often considered more environmentally sensitive. France’s President Sarkozy has encountered serious opposition in proposing a carbon tax on consumers to discourage fossil fuel use. He is running into problems not only among members of the opposition, but concerns have also been expressed by members of his own party. It appears that many French consumers (like their American comrades) are more concerned about the economy than climate change at the moment.

China, India and Beyond: If only a bit more than one-third of American households are willing to pay much of anything to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, it seems fair to ask what percentage of households in China, India and other developing nations are prepared to pay anything? A possible answer was provided recently by India’s environment minister, Jairam Ramesh, who released a report predicting that India’s greenhouse gas emissions would rise from the present 1.2 billion tons to between 4 and 7 billion tons in 2030. The minister said the “world should not worry about the threat posed by India’s carbon emissions, since its per-capita emissions would never exceed that of developed countries.” . At the higher end of the predicted range, India would add more greenhouse gas emissions than the United States would cut under even the proposed 80 percent reduction scheme. Suffice it to say that heroic actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions seem unlikely in developing countries so long as their citizens live below the comfort levels of Americans and Europeans.

Lower Standard of Living not an Option: I have been giving presentations on this and similar subjects for some years. I have yet to discern any seething undercurrent of desire on the part of Americans (or the vast majority anywhere else) to return to the living standards of 1980, much less 1950 or 1750. Neither Washington’s politicians nor those in Paris or any other high income world capital are going to tell the people that they must accept a lower standard of living. Nor is there any movement in Washington to let the people know that their tolerance for higher prices could well be insufficient to the task.

For Washington, the dilemma is that every penny of the higher costs will hit consumers (read voters), whether directly or indirectly. There could be trouble when the higher utility bills begin to arrive and it could mean difficulty in delivering on the primary policy objective of virtually all governments, which is to remain in power. This is not to mention the unintended consequences of higher prices on many key industries, notably agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation.

There is an even larger concern, however, and that is the stability of society. Harvard economist Benjamin Friedman, in The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth suggested from an economic review of history that economies that fail to grow lapse into instability.

A Public Policy Collision Course? A potential collision between economic reality and public policy initiatives could be in the offing. Many “green” proposals are insufficiently sensitive – even disdainful – towards the concerns of everyday citizens. This suggests that politically there should be an emphasis only on the most cost effective strategies. In a democracy, you must confront to the reality that people are for the most part more concerned about the economy than about strategies meant to slow climate change.

The imperative then is not to ignore the problem, but to focus on the most rational, low-cost and effective greenhouse gas emission reduction strategies. Regrettably, it does not appear that Washington is there yet. The special interests whose agendas are to cultivate and reap a bounteous harvest of “green” profits or to convert the “heathen” to behaviors – such as riding transit and living in densely packed neighborhoods – that they have been advocating long before the climate change issue emerged.

Those concerned about the future of the environment also have to pay attention to reality. Reducing greenhouse gases is not a one-dimensional issue. Environmental sustainability cannot be achieved without both political and economic sustainability.

Note 1: The Rasmussen question was asked of individuals. It is assumed here, however, that the answers related to households. One doubts, for example, that a queried mother answered with an assumption that she would pay $100, her husband would pay $100 and each of the kids would pay $100, but rather meant $100 for the household, since, to put it facetiously, few households devolve their budgeting to the individual members.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

”

-

Florida Drifts Into the Morass

By Richard Reep

Regarding Florida’s new outmigration, “A lot of people are glad the merry-go-round has finally stopped. It was exhausting trying to keep up with 900 new people a day. Really, there is now some breathing room,” stated Carol Westmorland, Executive Director of the Florida Redevelopment Association at the Florida League of Cities. Now that surf and sand are officially unpopular, the urban vs. suburban development debate has caught developers and legislators in a freeze frame of ugly and embarrassing poses at local, regional, and state levels.

In South Florida, Miami’s city commissioners narrowly defeated a move to institute a form-based code on August 7, which would have increased regulation in the most populous city in the state. This code would have rigidly set Miami’s density levels and regulated building form all the way down to the location of the front door. It constituted a surprising hometown defeat for Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberg, originators of the New Urbanism movement and the prime consultants hired to create the code. Commission Chairman Joe Sanchez, worried about restricting people’s use of property, stated that Miami 21 “exposes us to tens of millions of dollars in lawsuits from loss of property value.” Not ready to throw in the towel, however, the New Urbanists are appealing the vote in two public hearings. “We’re confident that the issues can be resolved,” stated Maria Mercer, who works for DPZ. The commissioners may be worried about lawsuits. The people seem to be even more concerned about Big Brother fussing about their property, judging from the public input on the code’s website.Of course, the press has decried this as a vote for “sprawl,” rather than a vote for common sense. By now, the language of growth management has become so riddled with red-baiting words such as “sprawl” posed against lofty ideals such “smart growth” that the public can make no real sense of development proposals anymore. It is easy to see why New Urbanism was so seductive, for it seems to solve every problem once and for all – this goes here, that goes there – and there would be no more debate…unless, of course, the Master Planner made an error somewhere. But, like most consultants, the Master Planner has moved on to the next job and isn’t in charge of living with his plan. If he labels low-cost development “sprawl”, then so be it. And if he deems high-cost development “smart growth,” then so be it. Just like Ramses in The Ten Commandments, “So let it be said – so let it be done.”

Blackballing suburbs with words such as “sprawl” is dissonant to most voters who, after all, live in these supposedly awful places; likewise words like “walkable urban cores” often conjure up the reality of parking and traffic nightmares. Then there’s something called the marketplace. Florida is becoming less about retirees, and more about families. The much ballyhooed flurry of high-density urban projects doesn’t seem to fit the lifestyle of cars and kids and soccer practice too well.

Then there’s the other downside of new urbanist growth, which is its cost. Young, single service workers and retirees – a natural market for these urban villages – cannot afford either the pricey real estate or the stiff maintenance fees. On the other hand, Florida’s upwards of about 300,000 empty single-family homes, by the Orlando Sentinel’s count, could provide a natural lure to families, more so than the 65,000 or so condominium units on the market in the state. This so-called “overhang” of 3 to 5 years of unsold inventory only serves to terrify homeowners who remain in the state and have to deal with depreciating property values for some time in the future.

Clearly more density has been no more successful than the most mindless sprawl. The New Urbanists’ often shrill rhetoric has frightened many planners into pushing density on Florida’s fleeing population. The disaster that is Miami’s downtown and beachfront may be the best known, but throughout the state Florida’s high density developers and landowners are facing foreclosures, fading credit, and loss of business on an unprecedented scale. Those who came late to the party – witness poor Hollywood, Florida, a city which finally got its act together and aggressively redeveloped its downtown – look like empty movie lots. Elsewhere in cities across the state, vast tracts have been razed, rezoned for high density and now lie fallow or unfinished, giving the face of Florida a remarkably post-apocalyptic quality.

Neil Fritz, Hollywood’s Economic Development Director, is sanguine about the dire straits of his town. “Oh, the urban areas will come back before the suburbs,” he stated recently. But in reality, downtown condominiums are a latecomer to the Florida scene, and are a forced market. They were viable largely because they compared favorably to single family detached dwellings in terms of price and convenience.

In fact, quite the opposite is likely to occur, with the single family suburb – particularly those located near jobs – rebounding first as people’s natural preference, as it has been for over a hundred years. This might chagrin the New Urbanists, who spent a great deal of effort inventing such earnest fantasies as a “sprawl repair kit”, even though safety, mobility and open space remain deeply ingrained in the American lifestyle. Also, the high-density movement was fed by investors and owners of second homes – rare commodities in this post-crash world.

Overdevelopment is easy to blame on poor government, which allowed developers to overbuild on credit, but as with the financial crisis in general, there is enough blame to go around. What municipality would not like dense urban cores full of affluent taxpayers enjoying lattes on the boulevard? This dream sadly has turned to the reality of empty storefronts, condos being converted into low-income rentals, or worse yet, empty lots being assessed at their lowest possible taxable value. The fringes of most urban areas continued to be developed at low density, and while they are suffering the same fate as the denser areas now, the effect is less profound since it is more spread out.

Florida’s government just has no place to turn for more revenue, and relies mostly on property taxes and fees. Its main economic engine is development. Local governments, increasingly unable to pay for services, naturally encouraged density as a way to levy more and more property taxes, largely ignoring the long-term economic viability of specific developments. So-called “smart growth” indeed seemed pretty smart to cities and counties needing the taxes that they believed dense urban cores might someday generate.

The best hope for Florida lies neither in the God-like precepts of the New Urbanist movement, nor in the hands of the developers, but rather in the hands of intelligent, humanistic conversation revolving around a sense of shared community and deeper values. With the internet as a tool, cities could be encouraging citizen input in advance of a proposal, rather than the old, 20th century tool of public meetings. This conversation is necessary as our legislators and developers dance their kabuki dance around imagined future prosperity. Florida seems to be drifting aimlessly, as no one at the state level seems to be concerned about the loss of population, instead congratulating themselves on creating the next boom.

The cities and counties of Florida would do well to use this interregnum to retool their public process to give people more access to the right information up front. By allowing internet-based review and participation, people can provide intelligent input into development proposals. Armed with the right information, Americans historically have made excellent decisions, and Florida can become an example in how to better manage its single most important industry. In the meantime, the leadership of Florida would do well to examine the negative connotations of “sprawl” when describing the native habitat of their voters and taxpayers, and examine the consequences of encouraging density for a market that has yet to exist, and may not exist for some time to come.

Richard Reep is an Architect and artist living in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

-

The Kid Issue

Japan’s recent election, which overthrew the decades-long hegemony of the Liberal Democratic Party, was remarkable in its own right. But perhaps its most intriguing aspect was not the dawning of a new era but the emergence of the country’s low birthrate as a major political concern.

Many Japanese recognize that their birth dearth contributes to the country’s long-standing economic torpor. The kid issue was prominent in the campaign of newly elected Democratic Party Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, who promised to increase the current $100 a month subsidy per child to $280 and make public high school free. The Liberal Democrats also proposed their own pro-natalist program with a scheme for free child day care.

Japan’s predicament seems obvious. Its fertility rate has dropped by a third since 1975. By 2015 a full quarter of the population will be over 65. Generally inhospitable to immigrants, Japan could see its population drop from a current 127 million to 95 million by 2050, with as much as 40% of the population over 65 years of age. By then, no matter how innovative the workforce, Dai Nippon will simply be too old to compete.

While Japan’s demographic crisis is an extreme case, many countries throughout East Asia and Europe share a similar predicament. Even with its energy riches, Russia’s low birth and high mortality rates suggest that its population will drop 30% by 2050 to less than one-third of that of the U.S. Even Prime Minister Vladimir Putin has spoken of “the serious threat of turning into a decaying nation.”

Russia’s de facto tsar has cause for concern. Throughout history low fertility and socioeconomic decline have been inextricably linked, creating a vicious cycle that affected once-vibrant civilizations such as as ancient Rome and 17th-century Venice.

Persistently low birthrates and sagging population growth inevitably undermine the growth capacity of an economy. Children provide a large consumer market and push their parents to work harder. By having children, parents also make a commitment to the future for themselves, their communities and their country.

In contrast, a largely childless society produces other attitudes. It tends to place greater emphasis on leisure activities over work. It also shifts political pressure away from future growth and toward paying pensions for the aging. An aging society is likely to resist risky innovation or infrastructure investments meant to serve future generations.

Of course, on a global level, lower birthrates should be seen as a positive. Population growth projections made around the time of The Population Bomb, Paul Ehrlich’s widely acclaimed 1968 Malthusian tract, which predicted global mass starvation, have turned out to be well off the mark. Global population growth rates of 2% in the 1960s have dropped to less than half that rate, and projections of the number of earth’s human residents in 2000 overshot the mark by over 200 million.

This pattern is likely to continue: growth rates will drop further largely due to an unanticipated drop in birthrates in developing countries such as Mexico and Iran. These declines are in part the result of increased urbanization, the education of women and higher property prices. The world’s population, according to some estimates, could peak as early as 2050 and begin to fall by the end of the century.

Yet in some places, like Japan, declining birthrates may already be too much of a good thing. The same is true elsewhere in East Asia, particularly in China, where the one-child policy has set the stage for a rapidly aging population by mid-century. Fertility is particularly low in highly crowded Asian cities like Tokyo, Shanghai, Tainjin, Beijing and Seoul.

Over the past few decades a rapid workforce expansion fueled the rise of the so-called East Asian tigers, the great economic success story of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. But within the next four decades most of the developed countries in East Asia, as well as Europe, will become veritable old-age homes: A third or more of their populations will be over 65, compared with one in five in the U.S.

Not that the U.S. doesn’t also have to cope with an aging population and lower population growth. But comparatively speaking it maintains a relatively youthful, dynamic demographic. Its fertility rate is about 50% higher than Russia’s, Germany’s or Japan’s and well above those of China, Italy, Singapore, Korea and virtually every country in the former eastern Europe.

The reasons for this divergence with other advanced countries likely includes such things as continuing immigration, more land, larger houses, a strong aspirational culture and a higher degree of religious affiliation. Whatever the cause, a younger demography could lead to a relatively brighter future for America than is now commonly assumed.

Additionally, in the next decade the U.S. will benefit from a millennial baby boomlet, as the children of the original boomers start having offspring. This next surge in population may be delayed if tough economic times continue, but over time it will translate into a growing workforce, sustained consumer spending and will likely spur a rash of new creative inputs.

On the surface, these trends should help America to maintain a growing economy while its main competitors fade. By 2050 Europe’s economy could be half that of the U.S. But this is not inevitable. As in Japan, some leaders in European countries understand they cannot sustain prosperity with a steadily declining workforce.

Many European countries are boosting benefits for families. In some, a pro-natalist policy is also being driven by concerns about the preservation of national cultures. In contrast to America, a country defined by immigration, most European countries – as well as Japan, China and Korea – have been far more resistant to outside influences.

The rise of immigration in recent decades has led to growing European nativist movements. Many Europeans, including liberal ones, are less than sanguine about the long-term consequences of Muslim birth rates now three times higher than those of indigenous Europeans. If current trends continue, according to the Brookings Institution, the Muslim population of Europe could double by 2015 while the non-Muslims shrink by 3.5%. Without a sustained boost in baby-making among native Europeans, much of the continent may soon confront the prospect of an essentially Islamic future.

But even so, attempts to foster a revival in European birthrates will face strong opposition from environmental activists who have amassed enormous influence. Some consider procreation of carbon-belching E.U. citizens as something close to anathema. In Great Britain, Jonathan Porritt, chair of the U.K.’s Sustainable Development Commission has advocates cutting the island’s population in half as a way to reduce global greenhouse gases.

For their part, some America greens have expressed concern over our country’s relative fecundity. The president’s science adviser, John Holdren, a longtime protégé of Malthusian prophet Ehrlich, has in the past spoken about the need to limit families to two children. On the right, nativists also fear that too much of our new population will be of Asian or Hispanic descent.

These pressures could lead to curbs on immigration, which would slow population growth. Other steps being considered by administration planners, such as cramming Americans into smaller houses in urban centers, would clearly discourage family formation. A persistently weak economy would do the same.

Yet those favoring strong steps to curb population here first should think of the consequences. As the Japanese increasingly recognize, it’s better to experience some population growth than to become a giant nursing home. A somewhat youthful, gradually growing population certainly may create considerable environmental and social challenges, but a scenario of persistent decline and rapid aging seems far worse.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History

. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.

-

Amtrak Runs Off The Rails

When the United States was in the money, the Congress grudgingly voted Amtrak a $1 billion subsidy every year, and then engaged in histrionics about how it might be cheaper to send most passengers to their destinations on private jets.

Then oil went to $140 a barrel, the United States dropped into recession, and one of the answers was to vote $12.9 billion in stimulus money, over the next five years, to Amtrak, the railroads, and state-supported transportation agencies.

Even though the American freight-train business has enjoyed a renaissance in the last twenty years — companies like the Burlington Northern Santa Fe and CSX are admirable for their competitive spirit and financial results — I am skeptical that Amtrak is the company that can lead the way to the re-birth of U.S. passenger service. Freight, let’s remember, only flourished when Conrail was privatized and the industry deregulated.

To be clear, the $8 billion appropriated for high-speed corridor service has yet to be earmarked, and is best understood as discretionary funding that can be doled out to the states, if not to loyal unions. For his part, Senate majority leader Harry Reid hopes to open a drawbridge to fund high-speed rail service between Anaheim and Las Vegas.

Somehow, it is hard to imagine that the U.S. can restore its economic prosperity by rushing heavy rollers to the blackjack tables in Vegas.

Now in its thirty-ninth year of operations, the government-controlled Amtrak provides good service between Boston, New York and Washington, and Los Angeles and San Diego. Elsewhere, it’s a land cruise company.

Beyond the corridors, Amtrak plies routes that were hastily drawn in 1971 to insure that they touch as many congressional interests as possible. That means meandering sleepers from New Orleans to Los Angeles, or Chicago to Seattle, which are a delight to vacationers (myself included), but inconsequential to the business of America, which drives or flies in order to get somewhere. Amtrak handles less than 1% of America’s intercity travel.

To defend Amtrak for a moment, it has been chronically under-funded, owns little of the track on which it operates, defers its schedule to freight interests, and is hostage to union rules, Congress and microwavable food. European trains get more subsidies in a year than Amtrak has gotten in its lifetime.

So will the $12.9 billion give the United States a passenger railroad network comparable to those that are now flourishing in Europe?

Before answering the question, let’s take a very quick rolling stock of what European railroads have on offer:

In Switzerland, where I live, the trains or a bus connect every village, town and city in the country. Geneva has more than 100 trains daily. Austin, Texas, a comparable city in terms of size, has two. But the railway is expensive for foreigners who visit the country. Round trip from Geneva to Zermatt for a family of four is about $600. Nonetheless, the rail network is a national asset.

The German passenger railway, Deutsche Bahn, is incomparable. Nothing matches its speed, comfort, and service. Its Inter-City Express trains (ICEs) are the best in the world for the cost, not to mention the beer that’s served.

The United Kingdom, which has privatized much of what was BritRail, is a mixed bag of flash roads. Private companies are now competing for passengers, which means lovely new carriages, and better pork pies on the tea trolleys. But neither the private companies nor the government is spending what is needed on Britain’s roadbed and infrastructure, which explains some of the horrible accidents in the system.

France has its Train à Grande Vitesse (TGV), which operates on segregated, elevated high-speed track, and makes the runs from Lyon and Avignon to Paris not much longer than local commuter service. I find its seats cramped in second class (too airliner-ish), and French stations are dingy, but otherwise the TGV is a model train. A comparable system in the U.S. could reduce the trip from New York to Washington or Boston to less than two hours. But it would mean building a new interstate for trains.

Italy has some excellent trains, and fast ones too. I know this, because I’ve seen them speed by as I have stood on platforms in Italy. But I never seem to catch any of them. The trains I ride have dirty seats, broken air conditioning, and inexplicable delays in places like Domodossola.

Eastern European night trains — I am partial to these, I confess — include heavy sleepers that go from Ljubljana to Belgrade, or Iasi to Bucharest, with reasonable fares, starched sheets on the berths, brandy at breakfast, and the chance to visit such exotic places as Debrecen, Lviv, and Chisinau.

The Russian Railways has, remarkably, become an excellent company, with improved passenger and freight services, including trans-Siberian container shipping that can get boxes from the Pacific to Berlin in less time than cargo ships.

How does Amtrak compare, and how is it likely to improve with stimulus funds?

Amtrak already looks good on one account: Europe’s international reservation system is medieval. Amtrak is miles ahead of Europe here. This summer I tried, in person and on the web, to book a sleeper from Geneva to Sevastopol, and failed.

In Europe, international travel usually requires a trip to the ticket window at the station. Even simpler journeys, when they cross borders, are either prohibitively expensive or impossible to book. Geneva to London comes in at about $400; EasyJet does it in an hour for $50.

While I am all for spending stimulus money, or any money, on American passenger service, I have yet to see anything remotely like a good strategic plan for its restoration. The glossy maps projecting new corridor services depend on the states, not Amtrak, to realize the dreams.

Nor am I sure that throwing money at the Amtrak model will do much more than refurbish some Amfleet coaches and make congressmen look good in mid-term elections. The railroad, like many in American history, strikes me as better at delivering pork than passengers. The current chairman is a former small-town, Illinois mayor, and Joe Biden’s son was a board member until February 2009.

Perhaps equally important, where is Amtrak’s passion for railroading? Why hasn’t the route map changed in forty years? Where are the car-carrying trains, the elegant stations, the sleepers that cater to business people with showers and wi-fi, or even the special tourist trains that would take travelers across America to Civil War battlefields, major league baseball games, rock concerts, or national parks?

Why do cities like Phoenix or Louisville have no trains at all? Where are the creative railroad financiers, selling sleeping cars as timeshares or condos? If it’s truly a government-run corporation, why aren’t there more investment-grade Amtrak bonds in world markets?

Here’s another irony of the railroad stimulus package: Freight companies are prospering with deregulation and private capital, but Amtrak is running late while on the dole.

Right now we’re in a golden age of railroads, much of it funded with investor capital. The common stock of large American railroads is attracting serious money, including that of Warren Buffet.

Around the world, private luxury trains are crossing Russia, India, China, Tibet, the Silk Road, the Alps, and the Andes. In Asia, investors are plotting to complete the line from Singapore over the Burma Road to China. A company in Africa charges about $30,000 — and gets it — for a deluxe train trip from Cape Town to Cairo. But bureaucratic protectionism keeps these dynamic groups from operating in the United States.

After World War II, America traded in the greatest railroad system in the world for interstate highways, sleazy rest stops, and now-crowded airports. Today, GM is broke, gas is three dollars a gallon, and politicians have to kowtow to Saudi princes.

I would love to think that for $8 billion, corridor service would flourish and that German-style trains would pop up around the country. Heck, I would love to ride a Romanian sleeper between New York and Bangor, Maine.

Despite my hopes, my fear is that the transportation stimulus money is probably going to end up on a roulette wheel in Vegas.

Amtrak Empire Builder at Marias Pass, Montana. Photograph by Alex Mayes.

Matthew Stevenson was born in New York, but has lived in Switzerland since 1991. He is the author of, among other books, Letters of Transit: Essays on Travel, History, Politics, and Family Life Abroad

. His most recent book is An April Across America

. In addition to their availability on Amazon, they can be ordered at Odysseus Books, or located toll-free at 1-800-345-6665. He may be contacted at matthewstevenson@sunrise.ch.

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN on Planetizen regarding growing cities

“Joel Kotkin discusses the role of these emerging global cities, and why the will be so important to the future of the world.”

-

Executive Editor JOEL KOTKIN on Whipple World regarding Texas

“Joel Kotkin, an urbanologist based in California, recently compiled a list for Forbes magazine of the best cities for job creation over the past decade. Among those with more than 450,000 jobs, the top five spots went to the five main Texaplex cities. A study by the Brookings Institution in June came up with very similar results. Mr Kotkin particularly admires Houston, which he calls a perfect example of an “opportunity city”—a place with lots of jobs, lots of cheap housing and a welcoming attitude to newcomers.”