Most American urban economic development and revitalization initiatives seek to position communities to attract high wage jobs in the knowledge economy. This usually involves programs to attract and retain the college educated, and efforts to lure corporate headquarters or target industries such as life sciences, high tech, or cutting edge green industries. Almost everything, whether it be recreational trails, public art programs, stadiums and convention centers, or corporate incentives, is justified by reference to this goal, often with phrases like “stopping brain drain” and “luring the creative class”.

The future vision underpinning this is a decidedly post-industrial one. This city of tomorrow is made up of people living upscale in town condos, riding a light rail line to work at a smartly designed modern office, and spending enormous sums – with the requisite sales tax benefits – entertaining themselves in cafes, restaurants, swanky shops, or artistic events.

In contrast the factory has no place in this future city. Indeed industry is considered a blight that needs to be eliminated or repurposed. What were once working docks are to be converted to recreational waterfront parkland. Warehouses and small factories become the site for developing lofts, studios, or boutiques. This urban economy is based almost solely around intellectual work and services, not physical production.

But there is a problem with this equation. In almost any city, the bulk of the people do not have college degrees. According to Brookings, the average adult college degree attainment rate for the top 100 metro areas is only 30.6% In the many years it will take to raise this, what are the rest of the people supposed to do for a living? Younger cohorts are better educated than their grandparents, so this will improve over time. But better educated for what? Not everyone is cut out, or wants to be a stock-trader or media consultant. We have to think about those who would rather work with their hands, or are better suited for that kind of work.

The vision touted by too many urban boosters is that of an explicitly two-tier society. There are elite, well paid knowledge workers in industries like finance, law, and technology, and then there is everybody else. Programs designed to boost knowledge industries turn out to be subsidies to cater to the most privileged stratum of society. The public is called on to pay for urban amenities for the favored quarter of the intelligentsia, with the benefit to the rest of the people assumed.

But little thought is given as to how everyone else will get by, other than working in low wage service occupations catering to the privileged. In the Victorian era, they called this going “into service”. Today we might think of them better as globalization’s coolie class.

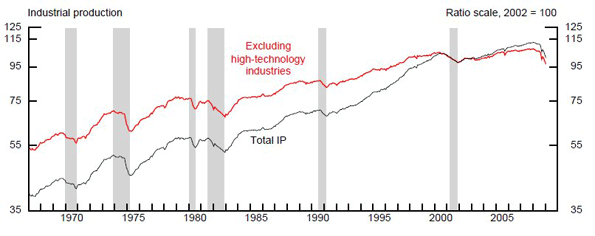

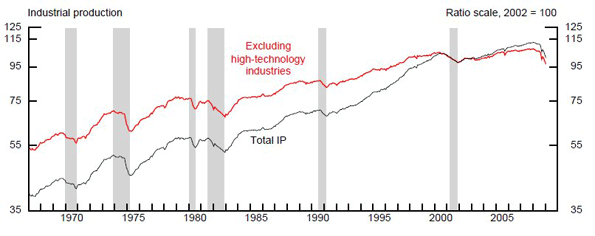

Beyond this, can we as a country prosper if we don’t actually make things anymore? Some of the fear of manufacturing decline is overblown. Despite large scale job losses in the manufacturing sector, the US has continued to set industrial production records outside of recessions. However, as the chart below from the Federal Reserve shows, industrial production growth flattened significantly in the late 1990s.

Sadly, manufacturing has been hammered in this Great Recession. There will certainly be a cyclical upturn in output, but restructuring in the automobile industry portends a permanent reduction in domestic output in that sector among others. Unless carefully handled, increasing regulation of carbon emissions, along with the associated energy price rises, will encourage further offshoring to countries with few climate change obligations, such as China, India, Brazil and other developing nations.

Yet to remain both a prosperous and fair society, the United States must remain a manufacturing power. Manufacturing still provides the traditional route to middle class wages for those without college degrees. It also alone employs 25 percent of scientists and related technicians and 40 percent of engineers and engineering technicians.

Of course, the next wave of manufacturing will differ greatly from the past. Improvements in productivity and global competition mean a bleak future for large scale, low value-added, routinized production. The era where an assembly plant provided thousands of good jobs at good wages is a thing of the past other than for the lucky few. And where there are new factories, they are often in greenfield locations like the new Honda plant in Greensburg, Indiana – halfway between Indianapolis and Cincinnati – not urban centers. Polluting heavy industry like primary metals and refining really are incompatible with neighborhoods. So what is to be done?

One answer is to build a new industrial city focusing on small scale craft and specialty manufacturing with high value added. We’re seeing a precursor to this in the rise of organic farming and artisanal products of all kinds. TV shows featuring hip young carpenters renovating homes or gearheads tricking out cars and motorcycles make these professions seem glamorous. Magazines targeted at the global elite like Monocle scour the world in favor of the finest handcrafted products from old school workshops, building demand for these products. The New York Times Magazine recently did an article making the case for working with your hands, and also noted how digitally oriented designers are rediscovering the use of their hands. Perhaps it is no surprise that sociologist Richard Sennett turned his attention to the idea of the craftsman . In short, making things, craftsmanship, and quality are back in fashion.

. In short, making things, craftsmanship, and quality are back in fashion.

The challenge for urban economies is to develop this and put it on a sound industrial and economic footing. One key might be to inspire people to start these craft oriented businesses by tapping into people’s desire to purchase ethical and sustainable products. We increasingly see with foods and other items that people want to understand their provenance, to know who made them, how, with what, and under what conditions. Often today businesses catering to this desire are small scale “Mom and Pop” type operations, but there is no reason they can’t be done at greater scale, or expanded into areas like organic food processing, not just organic farming. American Apparel has done just that by manufacturing low cost, stylish clothing “Made in Downtown Los Angeles. Sweatshop Free.” at scale, for example.

Beyond craft products, reinvigorating small scale, specialty fabrication and other businesses, to rebuild an American version of Germany’s Mittlesand, creates another, often ignored option for urban economies. Quality, flexibility, responsiveness, and a willingness to do small runs are keys. These businesses can also underpin product companies higher in the value chain. They start building an ecosystem of local companies and expertise that can be useful for related or spin-off businesses. Jane Jacobs, and before her the great French historian Fernand Braudel, noted how cities could incubate many new enterprises because all the diverse products and services they needed were available locally. If you need to scour the globe looking for custom parts and services, it can quickly overwhelm a small business. That’s one reason American Apparel started in Los Angeles, which already had a network of garment producing firms and expertise to draw on. What’s more, these firms might be ideal candidates to take over empty strip mall or other space in decaying inner ring suburbs, helping to solve the “graybox” problem. Even Main St. locations could potentially benefit from businesses beyond traditional boutiques.

Today these types of specialty firms are often found in America’s largest cities, so they stand to benefit most from this. Smaller cities also need to figure out how to build this ecosystem. The culture needs to change too. Particularly in the Midwest/Rust Belt area, industrial labor has tended towards low skill, repetitive work in larger scale mass production industries. Retraining will be needed for these newer types of businesses, but this is vocational or skill training, not necessarily a college degree. It is a much more tractable problem.

Not only could this new manufacturing base be a source of urban middle class jobs for the non-college degreed, it would do something arguably more important. It links the fortunes of the new upscale urban residents, the people who are both the customers for many of these products and potentially also the entrepreneurs making them, with that of their less educated neighbors. For many owners, managers, and workers, it might bring into daily contact people who might not otherwise ever interact if one group worked in an office and another in a warehouse. Rebuilding that sense of community and commonwealth, that we are neighbors, fellow citizens, and all in this together, is critical to building a truly sustainable, well-functioning and broadly prosperous society.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.

Environmentalism has further accelerated the trend for the shrinking of the British home. The emphasis upon the Rogers-style compact city has been trumpeted by the Green Party and other environmental lobby groups because higher densities and small build theoretically cause less carbon emissions and use up less non-renewable sources of energy.

Environmentalism has further accelerated the trend for the shrinking of the British home. The emphasis upon the Rogers-style compact city has been trumpeted by the Green Party and other environmental lobby groups because higher densities and small build theoretically cause less carbon emissions and use up less non-renewable sources of energy.