Almost ten-years ago, the Milken Institute first released America’s High-Tech Economy which cataloged technology’s central role in propelling economic growth in high-wage jobs and value-added economic activity. Shortly thereafter, the dot-com and high-tech bubbles popped, leading many to conclude that the era of tech-driven economic development was over.

But the pessimists were wrong. A recovery in high-tech began in 2003 and served as an engine of regional growth through most of 2008. Communities with concentrations of knowledge-based industries – everything from information technology to biopharmaceuticals – have been able to create and retain high-paying jobs. And when economic growth returns, these industries will once again be at the forefront.

In the full study, we explain the patterns of growth in 19 high tech-categories. In each category, individual metro areas are ranked according to their performance as “tech poles.” The entire study and a complete explanation of our methodology can be found in the full report, downloadable from milkeninstitute.org.

This time around, we extended the study to include Canada and Mexico, whose economies have become ever more intertwined with that of the United States, including the high-tech sector.

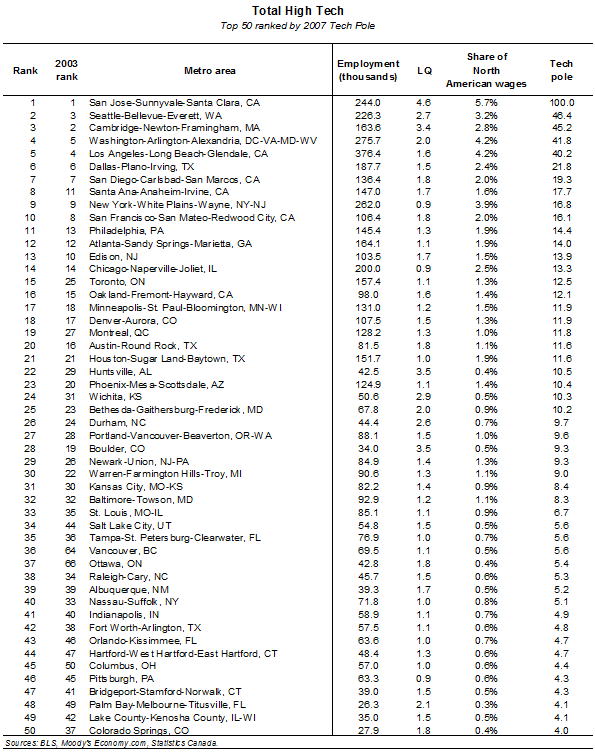

Top-Performing U.S. and Canadian Metros

1. Silicon Valley (the San Jose–Sunnyvale–Santa Clara, California metro area) remains the preeminent high-tech cluster in North America (and the world), although it’s once seemingly enormous lead over other regions has diminished somewhat. Even so, it retains an unrivaled capacity to capture locally generated intellectual property and to convert it into economically viable businesses. Its firms regard R&D as part of their very DNA; they see innovation as their core business mission rather than as a necessity that can be given short shrift when times during recessionary time.

In recent years, Silicon Valley has had to restructure its operations. Businesses are now more cost-conscious, outsourcing lower value-added functions while retaining the highest-valued and most creative elements. Manufacturing – in particular, manufacturing of heavily commoditized products – have been relocated. Thousands of jobs were lost, considerably more than were recovered over the past ten years.

The Valley’s famed Sand Hill Road venture capitalists are now more inclined to go abroad to India, China and Israel to fund new enterprises and to seek partners for their portfolios of start-ups. Many foreign-born engineers, software developers and tech-savvy entrepreneurs have left the area to lead a wave of technology entrepreneurship back home. This process is better termed “brain circulation” than brain drain, as these innovators are inclined to retain strong ties to former colleagues in Silicon Valley.

Still, Silicon Valley still ranks as first or second in six industry categories; it places among the top ten in 12 categories. Overall, its high-tech employment concentration is four-and-a-half times the metro average for North America. The San Jose metro may not dominate the technology landscape as fully as it did ten years ago, but its position is still unique.

2. Seattle-Bellevue-Everett’s second-place position on the tech pole index should be no surprise. The metro area employed 226,300 high-tech workers in 2007, just 17,700 fewer than San Jose. Seattle owes most of its stellar ranking, of course, to software, mainly Microsoft and its spinoffs, as well as aerospace.

Microsoft alone employs more than 33,000 workers in the metro, giving it first place on the tech pole index in software publishing. Seattle’s doesn’t just lead in software, it dominates the software landscape with a tech-pole score of 100, five times that of Cambridge. More than 23 percent of wages in North America’s software industry are paid to workers in the metro.

In addition, although no longer the headquarters town for Boeing, much of the firm’s operations remain in Seattle along with a bevy of aerospace sub-contractors. Altogether, Seattle employed 76,100 in aerospace products and parts manufacturing in 2007. Only Wichita, Kansas, has a higher concentration in aerospace. Seattle also ranks among the top ten tech poles in telecommunications and other information services.

3. The Massachusetts metro combining Cambridge,Newton and Framingham, is third on the tech pole index. Home to world-class research universities including Harvard and MIT, and the global leader in commercializing and transferring university research to the private sector, the metro area has an ecosystem of technology entrepreneurship that rivals Silicon Valley’s. The research intensity in the area has enabled it to be among the elite in generating and growing biotech start-ups, as well as attracting the research divisions of large pharmaceutical and biotech firms.

Particularly notable has been the Cambridge metro which stands as the top-ranked tech pole in scientific R&D services, a category that captures much of its biotech research. Scientific R&D employed 26,000 locally in 2007; these activities are nearly eight times more concentrated in the Cambridge area than in North America overall Cambridge also ranks second on the software index, and it makes the top ten in a total of nine categories.

4. Washington-Arlington-Alexandria is fourth among tech poles. The capital area is the North American leader in high-tech services, placing in the top ten in six out of eight high-tech service categories. Overall, firms in the Washington metro employed 275,700 high-tech workers in 2007, double the average concentration in North America.

The presence of much of the federal government in DC generates the need for massive data-processing support and attracts defense and aerospace contractors. By no coincidence, the metro Washington leads in computer systems design and related services, where it has more than five times the average concentration found in North America. In this sector it dominates other tech poles, with twice the score of second-place San Jose. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and its spin-offs in the biotech area aid the metro area’s performance.

5. Los Angeles–Long Beach–Glendale ranks fifth thanks to its still-vast aerospace footprint and the emergence of the technology-intensive segment of the motion picture industry. The area has a large university research base, with world-class institutions including Cal Tech, UCLA, and USC. They provide great depth in medical research, especially in the biotech area.

Los Angeles is the top tech pole in navigational, measuring, electromedical and control instruments manufacturing. This sector employed 36,200 local workers in 2007. Los Angeles is the headquarters of Northrop Grumman, and Boeing retains major operations in the area, making it fifth in aerospace products and parts manufacturing, with 38,000 jobs. Clearly, the inclusion of motion picture and video in our definition of high-tech industries boosts LA’s position in the rankings, but this decision makes sense in light of the field’s growing importance as a generator of value-added in high technology. Los Angeles has 32 percent of North American employment in motion pictures.

6. The Dallas-Plano-Irving, Texas, metro division is sixth on the tech pole index. Its strengths lie in information and communications technology hardware and data processing services. Overall, high tech employed 187,700 workers in 2007, for a concentration 50 percent above the North American average.

Dallas ranks second in telecom, and places third in communications equipment manufacturing. The metro is renowned for its Dallas-Richardson telecom corridor. And with Texas Instruments as its anchor, the metro places sixth on the semiconductor and other electronic component manufacturing tech pole index. The Dallas campus of the University of Texas has an outstanding engineering program that provides homegrown talent to local industry. Since 2003 Dallas has jumped a spot (to second place) in data processing, hosting and related services. A number of data processing centers are located here, with Electronic Data Systems as the anchor.

7. San Diego–Carlsbad–San Marcos is home to the world’s most geographically dense biotech cluster, with a strong position in telecom hardware and services and several other fields. San Diego employed 136,400 in high-tech sectors in 2007, 80 percent above the average North American concentration. The metro area placed in the top ten in a total of four high-tech sectors.

San Diego’s biotech network is anchored by the Scripps Research Institute, the Salk Institute for Biomedical Sciences, the Burnham Institute and the University of California at San Diego as well as dozens of mid-sized biotech firms and uncounted start-ups are located here, too. Qualcomm is the major player in the communication chips, while AT&T gives San Diego a presence in telecommunications.

8. San Diego’s neighbor to the north, Santa Ana–Anaheim-Irvine (Orange County) is eighth on the tech pole index, a jump of three places since 2003. High tech in the area is driven largely by medical equipment manufacturing, medical and diagnostic labs as well as measuring, electro-medical and control instruments manufacturing. But the presence of Broadcom makes it a key player in communication chips, too. Orange County ranks among the top ten in seven categories and exceeds the North American concentration in a remarkable 16 categories.

9. Part of the greater New York City area, the metro division of New York–White Plains–Wayne places ninth on the overall tech pole list. While the area is not particularly known for high-technology, it does employ 262,000 high-tech workers – tens of thousands more than Seattle. New York is second only to Los Angeles in motion pictures and video industries. It is also a key location for Internet portals, placing the area third in other information services.

10. San Francisco–San Mateo–Redwood City just made it the top ten in 2007, slipping from eighth in 2003. The dot-com bust hit San Francisco harder than any other tech-pole. However, the creativity of its entrepreneurs and high-skill level of its workforce give the metro the capacity to constantly reinvent itself. Biotech heavyweight Genentech was initially built around local university research. It ranks fifth among software publishers with major operations of Electronic Arts and Oracle. San Francisco is a major hub of data processing, hosting, and related services, where it ranks seventh. And it ranks just behind the DC metro in high-tech services.

11. The Philadelphia, Pennsylvania metro area was eleventh on the tech pole index in 2007, up two slots from 2003. The area hosts a number of pharmaceutical companies including Merck, Wyeth, and GlaxoSmithKline, as well as biotech firms including Cephalon. Philadelphia ranked seventh in scientific R&D services, up from 14th in 2003 thanks to biotech’s rising star. Philadelphia is strong in medical devices as well.

12. Atlanta–Sandy Springs–Marietta’s ranking is due largely from its first-place ranking in telecommunications. AT&T’s Mobility division is the biggest local player in telecom; overall the sector employs 37,900 workers in Atlanta.

13. Edison, New Jersey, placed third in pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing, with 16,800 workers. Major players include Bristol-Myers Squibb and Johnson & Johnson. Edison is a top-ten performer in telecommunications as well.

14. The Chicago, Illinois portion of the Greater Chicago metro ranks among the top ten in telecom and computer systems design and related services. Altogether, some 200,000 local workers were employed in high-tech industries in 2007. The two biggest high-tech firms: Motorola and Abbott Labs.

15. Toronto is Canada’s highest-ranking tech center, coming in 15th in North America.. And with 157,400 high-tech sector jobs it ranks tenth in terms of absolute size. Private-public research collaborations involving the University of Toronto and McMaster University have propelled the metro’s emergence as an attractive place for biopharmaceutical firms. Major players include GlaxoSmithKline and Apotex. Toronto is Canada’s leading center of computer systems design and related services, a category in which it ranks eighth in North America. The metro area has nurtured a thriving film cluster as well.

16. Oakland-Fremont-Haywood isn’t in the top ten finish in any of the 19 categories, it exceeds the average high-tech job concentration in 16 of them. Major tech employers include Oracle and Sybase.

17. Minneapolis–St. Paul–Bloomington owes its position to medical devices giants Medtronics and Boston Scientific. Overall, Minneapolis has a higher than average concentration of high-tech jobs in nine categories.

18. Denver-Aurora ranking comes in large part to its fourth-place finish in telecom. Qwest Communications is the largest employer in the metro area.

19. Montréal is Canada’s second metro to make the top twenty, and it’s up eight spots since 2003. Montréal boasts more than 127,000 high-tech jobs, with aerospace as a primary driver. Bombardier is headquartered here, contributing nearly 21,000 aerospace-related jobs, but Pratt & Whitney also has a large presence. Montréal’s aerospace cluster is supported by its formidable research capacity, a mix of four major universities and 197 research centers.

20. Austin–Round Rock, arguably the quintessential 21st-century knowledge-based community, rounds out the top twenty. Among high-tech industries, its highest concentration is in computer and electronic product manufacturing. Dell is headquartered here. But it is also favored by major presences of IBM, Applied Materials, Advanced Micro Devices, Flextronics and Samsung Austin Semiconductor.

Mexican States

To create a set of North American rankings that included Mexico, we had to utilize data at the state level rather than the metro level. Mexican data was only available through 2003, so we include it in the North American rankings only for that year. Note that use of state-level data pushes up total employment and wages, but also reduces the overall concentration of jobs in each sector.

Baja California, the state that makes up the northern half of the Baja California Peninsula and include the cities of Tijuana, Mexicali and Ensenada, is the top-ranking Mexican state in the tech pole index. Placing 15th in North America (in 2003), it employed 104,000 in high-tech sectors.

Foreign firms have been attracted by the Maquiladora Decree of 1989 that granted them a variety of incentives to manufacture in border areas for the purposes of export. Most products from these factories are intended for export to the United States or Canada so they are located in zones close to the U.S. border . The region was the top tech pole in audio and video equipment manufacturing.

Baja’s concentration of employment in electronic components actually exceeds that of San Jose, although it is largely made up of lower-wage production line jobs. This may also be the case in medical equipment and supplies manufacturing, where Baja leads North America in with 22,200 jobs, 16 times the average concentration. Overall, Baja California has more than three times the average North American job concentration in high-tech industries.

The Distrito Federal or DF which encompasses Mexico City and its immediate surrounding area, was the second-ranking Mexican state, placing 20th overall in North America in 2003. The DF was the top tech pole for telecommunications in North America in 2003, thanks largely to the location of giant Telefónicas de México (Telmex). The concentration of telecommunications in the region is nearly three-and-one-half times greater than average in North America and telecom employment (82,100) was nearly double that of second-ranking Atlanta.

The DF ranked sixth in pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing in North America, with 33,700 local workers – 13,000 more than the second-highest ranking North American metro.The ability to export Mexican film and television products to other parts of Latin America as well as a large home market has given the industry cluster around Mexico City a comparative advantage. Employment is actually the third largest of any of the locations on the list. Total high-tech employment in the DF is 17 percent more concentrated than the North American average.

Ross C. DeVol is Director of Regional Economics and the Center for Health Economics at the Milken Institute. He oversees the Institute’s research efforts on the dynamics of comparative regional growth performance.