The site plan logically should be the key to approval of a development project. Yet in reality, the plan is secondary to the presentation. My conclusions are based upon experience with well over a thousand developments over four decades, most in the mainland USA. And what I’ve observed is that the best site plan is only as good as the presentation that will convince the council or planning commission to vote “Yes” on it. No “yes” vote, no deal, no development.

Each presenter deals with the dog-and-pony show in his own way. There’s an endless variety of styles (or lack of styles). All of these public meetings have one thing in common: The neighbors (if there are any) will be there to oppose the new development.

Not Too Long Ago…

In the old days there were three factions: The developer presenting the plan, the neighbors opposing the plan, and the council listening to both sides. If the development was high profile, someone from the local press might also show up. The planning commission and council are fully aware that all plans will be met with neighborhood opposition, and they will have to listen to lengthy complaints along the route to approving (possibly) the plan.

In the past, the citizens sitting on these boards would most likely dismiss Elwood and Betsy Smith’s complaint about how a development in their back yard would invade their privacy, and would vote in favor of the new master planned community instead.

How It’s Different Today

Today there is often an additional audience. Televised meetings provide an entire region of neighbors. The on-screen council listens to the neighbor’s objections, no matter how absurd they may be, then answers directly to the camera, showing the general community watching at home that they really care about every citizen’s opinion. The council member must never appear too much in favor of the developer, as that could be misconstrued as not caring about the citizens he or she represents. A televised Council member hears the Smith’s complaint with a very concerned on-camera look, explains how maybe we have too many new homes in this town, and proceeds to tell viewers that the developer might want to consider a buffer and a drop in density. Concerns have changed from developing economically sensible neighborhoods to “please elect me Mayor when I’m on the ballot”.

Planning Outside The USA

Our first large site plan done outside the States was in Freeport, Bahamas. In 2000, when we were first contacted to design Heritage Village, we asked about doing presentations to the city council and planning commission to help move the approval process along. We were told that the development company and the regulating entity were the same, and if they liked the plan it would be built! That is exactly what had happened.

Our next attempt outside the USA was not so easy. In Mexico City when we asked to sit down with government officials to change policy to create better neighborhoods, the developer said… No. At the time, we did not understand why it was so critical that we were not to suggest changes.

We Discover A Superior Foreign System

We wrongly assumed that all planning outside the USA could have similar problems, with restrictions that were absurdly prohibitive for designing great neighborhoods. It was only when we worked in Bogota, Columbia last year that we had the opportunity to work within a system that may not be so backwards after all. Our request to meet with the authorities to show them new ways to design neighborhoods was met, as it had been in Mexico City, with an absolute… No.

We then asked for an opportunity to present the plan, and were told that was not necessary. Being that it was Columbia you can imagine our first thoughts. Cartels? Maybe corruption? The reality was much simpler. Since our plans met the minimums (they actually exceeded them), they were automatically considered approved. Imagine that – no neighbors to complain! If everything conforms, it should be approved … right? Just plain common sense.

Zoning-Compliant Projects Should Be Exempt From Public Meetings

When you think about it, why wouldn’t this work in the USA? if the development plan being submitted meets or exceeds the zoning and the subdivision regulation minimums, why does it need to go through any public approvals at all? The American developer often faces months or years of delays, enormous interest payments, and tens or perhaps hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on consultants and legal help to re-create plans that conform. Those massive sums could go towards making better neighborhoods, better architecture, better landscaping, less environmental impacts, and more affordable housing.

We’d Still Need Public Meetings

The public would still have plenty of input on regulation and zoning exemptions, where public citizen input is valuable. If a developer is proposing something that goes below minimums or does not conform to zoning regulations, then it is reasonable to go through the more time consuming process that we currently have. This brings up the question of how the developer would introduce something different to the written law. This could be a problem under typical PUD (Planned Unit Development) regulations, which typically allow blanket changes to the minimums when alternative designs are not covered by typical zoning.

This PUD Pandora’s box, once opened, can have devastating results if the regulators and the neighbors both agree that the plan is simply not good enough. The developer thinks the plan is just dandy as is, but in reality most PUD proposals are simply too vague to be functional. A battle of wills that can last years often ensues.

In the end , these expensive delays increase lot costs, and the home buyer ultimately pays. If a special ordinance such as PUD, Cluster Conservation, or Coving was specifically spelled out in a rewards-based — instead of a minimums-based — system, developers could get benefits for great plans complete with open space and connectivity, typically density and setback relaxations.

While writing Prefurbia, we began to ask ourselves, how did we take something so simple and let it get so out of control? The third world countries are progressive enough to actually allow developers who comply with the rules to quickly build their neighborhood. Maybe they are not so far behind us after all.

Perhaps our regulations and planning approach is intended to keep the system “busy” with billable hours. Imagine if we could get a conforming plan stamped, and the next day construction could begin. How many billable hours would be eliminated, how much construction cost and land holding interest saved? That would be very hard to calculate, but it’s likely significant.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it…” Al Gore, An Inconvenient Truth

The inconvenient truth won’t win us many friends in the consulting industry whose incomes depend upon generating billing time in meetings. But can we afford to continue down the path we are presently on? We need to take a hard look at the regulations. Are they written solely to provide the highest living standards? Or do they generate the highest billable hours for the consultants who propose them?

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable. His websites are rhsdplanning and prefurbia.com.

About 200 million years ago the continents began to drift apart as the globe separated into eight distinct tectonic plates. History will record that the financial tectonic plates of our world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. They have not stopped moving and the outcome of where they will end up remains uncertain.

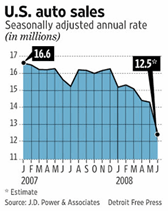

About 200 million years ago the continents began to drift apart as the globe separated into eight distinct tectonic plates. History will record that the financial tectonic plates of our world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. They have not stopped moving and the outcome of where they will end up remains uncertain. Fifty years ago General Motors owned more than 50% of the American market and automobile jobs made up one seventh of the US workforce. It was said that when GM sneezed the US economy caught a cold. GM shares now sell for less than a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now GM is about to enter bankruptcy.

Fifty years ago General Motors owned more than 50% of the American market and automobile jobs made up one seventh of the US workforce. It was said that when GM sneezed the US economy caught a cold. GM shares now sell for less than a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now GM is about to enter bankruptcy.  The New GM will become the platform for small fuel efficient cars, hybrids, electric vehicles and experimental technologies mandated by an ever demanding government. Its shareholders vanquished, The New GM will bear no resemblance to the car company that we have known for the last 50 years. Can the Chevy Volt rescue GM? The answer is no.

The New GM will become the platform for small fuel efficient cars, hybrids, electric vehicles and experimental technologies mandated by an ever demanding government. Its shareholders vanquished, The New GM will bear no resemblance to the car company that we have known for the last 50 years. Can the Chevy Volt rescue GM? The answer is no.