Cities today have more political clout than at any time in a half century. Not only does an urbanite blessed by the Chicago machine sit in the White House, but Congress is now dominated by Democratic politicians hailing from either cities or inner-ring suburbs.

Perhaps because of this representation, some are calling for the administration and Congress to “bail out” urban America. Yet there’s grave danger in heeding this call. Hope that “the urban president” will solve inner-city problems could end up diverting cities from the kind of radical reforms necessary to thrive in the coming decades.

Demographics and economics make self-help a necessity. Despite the wishful thinking of urbanophile pundits and policymakers, central cities have little realistic chance to reclaim their pre-1950 role as the dominant arbiters of American life.

Short of a catastrophic change, the country will remain predominately made up of suburban, exurban and small town residents. Since 2000, more than four-fifths of metropolitan growth has taken place in suburbs and exurbs. Economically, we see a similar pattern. According to a recent Brookings Institution study of 98 large metropolitan areas, only 21% of employees work within three miles of downtown. The report found that only three regions avoided the decentralizing trend.

The Brookings report and many others decry all these trends as promoting “sprawl,” but name-calling will not assure that urban areas can impose their political hegemony over the long run. The Obama administration may try to boost cities by imposing barriers to suburban growth, but these seem doomed to failure given both the preference of most Americans for lower-density lifestyles and the president’s demonstrated ability to count votes.

Rather than waiting for Barack, urban boosters should instead take up the New Testament injunction to “heal thyself.” Cities should have a chance to grow based on the roughly 10% to 20% of Americans who tell researchers they would like to live in a dense urban environment. With an extra 100 million Americans coming on line by 2050, cities could look forward to accommodating upwards of 20 million more people in the next few decades. As my grandmother would say, that’s not exactly chopped liver.

Yet in order to enjoy this repast, cities will need to address three fundamental and inextricably related issues: public safety, business climate and political reform. Of these, public safety is the most critical. From the earliest times, security has represented a critical pre-condition for urban success. The huge surge in urban crime during the 1960s, for example, played an enormous role in the precipitous decline of cities in the ensuing decades.

Conversely, improvements in public safety after 1990–notably in New York and Los Angeles but also in other large cities–helped slow the out-migration from urban cores and attract new residents, mostly young educated professionals and immigrants. Now urban crime may be on the rise, and could again threaten new growth.

This is worrying because urban crime rates, notes demographer Wendell Cox, remain still three times higher than those of surrounding suburbs. Almost all the highest crime areas in America can be found in urban settings, while the safest places tend to be in suburban towns.

Even the president’s much-celebrated hometown of Chicago suffered roughly a murder a day last year. On the city’s MTA trains, robbery soared 77% between 2006 and 2008. Now there’s also more than a stickup a day.

Hard economic times may exacerbate these problems, with an estimated 250,000 more Chicagoans predicted to fall into poverty by the end of the year. More widely, unemployment among core urban populations–young people, minorities and immigrants–is on the rise, even more than in the general population. Indeed, for the first time since the mid-1990s, the foreign born now suffer a higher rate of joblessness than the native born.

Yet even in the face of a tough economy, few cities seem to focus on long-term middle-class job creation. Most seem to prefer to indulge in marginally useful taxpayer-subsidized prestige projects like convention centers, arts complexes, ball parks and arenas. Meanwhile, the core issues stifling growth–high taxes, stiff regulatory burdens and sometimes corrupt governments–remain largely ignored.

Recently while researching the middle class in New York, I met many otherwise committed urbanites considering leaving to less costly, lower-tax and more business-friendly locales. Up until recently, this problem was somewhat obscured by spectacular earnings on Wall Street, which engendered the growth of an extensive “luxury economy” largely insulated from high costs. But even Timothy Geithner won’t be able to bail out this favored segment of the economy ad infinitum.

Instead cities, including New York, will have to diversify to less gilded industries. Increasingly cities will need to rely on small companies, micro-enterprises and self-employed high-tech artisans to drive their economies. To keep them there, they will need to attend to basic services–education, police and transportation–while managing to curb taxes and regulations.

This will necessitate confronting the largest source of high city costs: public employee salaries and pensions. This problem is not unique to core cities, but tends to be more severe in urban areas where public employee unions often dominate local politics.

Finally, cities need to address their educational systems. Despite all the talk of urban educational reform, the urban dropout rate, according to a recent study of the nation’s largest cities by America’s Promise Alliance remains around 50%, roughly 20 points higher than the rate for suburbs. Poor-quality urban schools drive out both the middle class and the most upwardly mobile segment of the working class.

Even more money from Washington won’t solve this problem. Cleveland, with a 38% graduation rate, spent far more on students per capita than Ohio’s statewide averages. In contrast, the surrounding suburbs enjoyed an 80% graduation rate.

Are cities capable of changing their governance for the better? In the 1990s, the emergence of tough, reform-minded mayors like New York’s Rudy Giuliani, Indianapolis’ innovative Steven Goldsmith, Richard Riordan in Los Angeles and Houston’s hard-driving Bob Lanier all sparked urban revivals in their cities.

Today, however, there are few such personages; Houston’s Bill White is one glaring exception. Yet without an infusion of bold new leadership, the future of American cities, although not universally bleak, will not be nearly as bright as it should be. Rather than a constellation of strong, reviving cities, we can envision the emergence of a less promising set of scenarios.

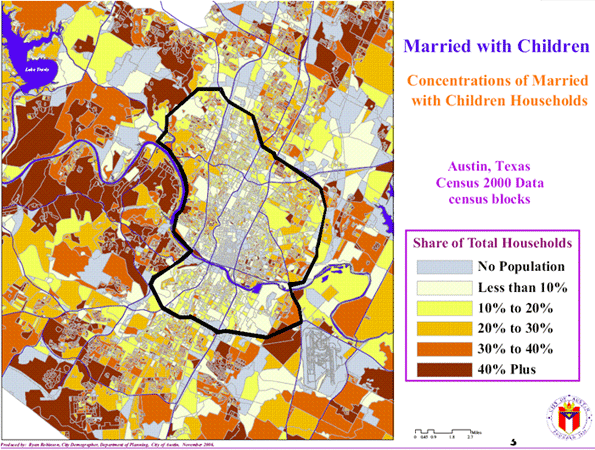

One archetype will be the Bloombergian “luxury city,” a very expensive urban area dominated by the wealthy and their servants, students and nomadic young workers as well as the poor. The affluent will drive this growth, but only in a relatively few neighborhoods in attractive places like New York, Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles, Seattle, Portland, Denver and Minneapolis.

San Francisco may presage this urban form. Already middle-class families are becoming scarce in the city by the bay. The place seems increasingly something of a Disneyland for privileged adults, exempting of course the large homeless population. “A cross between Carmel and Calcutta,” jokes California historian and San Francisco native Kevin Starr.

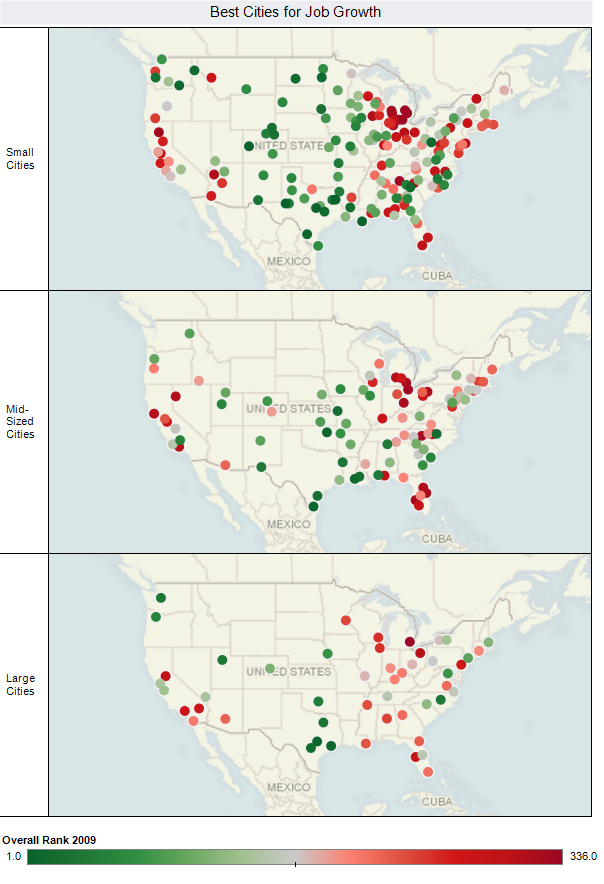

At the opposite end of the spectrum lie those cities consistently at the bottom of our Worst Cities For Jobs ranking. Despite some zones of gentrification, such once-great cities as Detroit, Cleveland, Memphis, Baltimore and Philadelphia could continue to suffer persistently high rates of poverty, diminished populations and high crime rates.

Not that this has to be. These areas could stage a real resurgence if their governments determine to throttle criminals, improve basic services and nurture small businesses. Low housing prices, cheap land and, in some cases, strategic locations could attract businesses as well as some of the millions who will be seeking out an urban lifestyle in the coming decades.

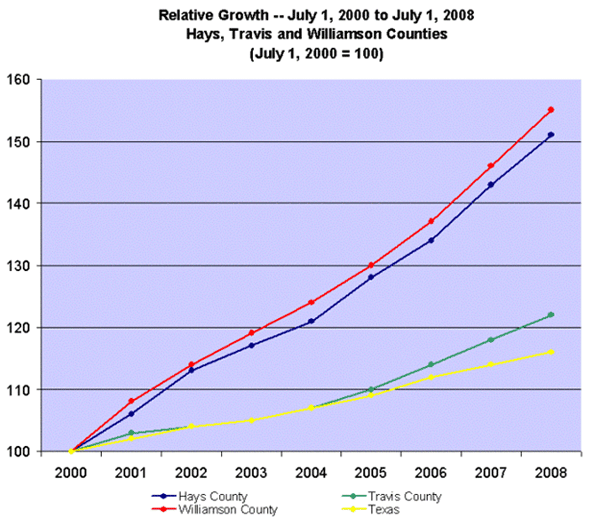

Currently the brightest hopes for America’s urban future lie with newer, “aspirational,” middle-class-oriented cities such as Houston, Dallas, Austin, Phoenix, Raleigh-Durham, Charlotte and Orlando. Although some are now suffering from the recession, these places will benefit from both lower costs and more business-friendly regimes. Primarily suburban in nature, many of these cities have worked to develop attractive dense urban districts, which could expand much further over the next few decades.

There remains nothing pre-determined about the urban future. Some cities may surprise us by reviving strongly while others may continue to disappoint. Success will depend not on Washington, but on how each city addresses the basics of safety, economics and governance. Grasping this fundamental truth constitutes the first step towards creating a sustainable long-term urban resurgence.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History and is finishing a book on the American future.

and is finishing a book on the American future.