Over the past year, coverage of the economy appears like a soap opera written by a manic-depressive. Yet once you get away from the coasts – where unemployment is skyrocketing and economies collapsing – you enter what may be best to call the zone of sanity.

The zone starts somewhere in Texas and goes through much of the Great Plains all the way to the Mexican border. It covers a vast region where unemployment is relatively low, foreclosures still rare and much of the economy centers on the production of basic goods like foodstuffs, specialized equipment and energy.

People and companies in the zone feel the recession, but they are not, to date, in anything like the tailspin seen in places like the upper Great Lakes auto-manufacturing zone, the Sunbelt boom towns or, increasingly, the finance-dependent Northeast. Last month, for example, New York City’s unemployment experienced the largest jump on record.

“That whole swath from Texas and North Dakota did not see either the bump or the decline,” notes Dan Whitney, a principal at Landmarketing.com, a real estate research company based in Kansas City, Kan. “People have a more conservative nature here. It’s just saner.”

The housing market is one indicator of greater sanity. Kansas City housing prices dropped 7% between 2006 and 2008, compared with 10% in Chicago, 15% in San Francisco, 20% in Washington, D.C., and over 30% in Los Angeles. Houston and Dallas, the Southern anchors of the zone, have seen little movement either way in prices.

One key measurement is affordability. The median multiple for Kansas City housing – that is the number of years of income compared with a median-priced house – has remained remarkably stable at under 3.0. In contrast, notes demographer Wendell Cox, the ratio approached up to 10 in places like Los Angeles and San Francisco, as well as something close to 7 in New York and Miami.

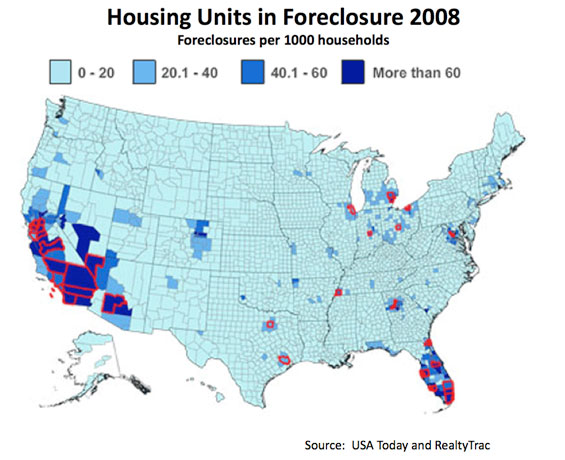

The result has been that foreclosures – the key driver of many regional economic collapses – have been relatively scarce throughout the zone. This USA Today map reveals how the foreclosures are heavily concentrated in Florida, California, Arizona and Nevada, as well as parts of the old Industrial Belt of the Great Lakes.

Analysis by my colleagues at Praxis Strategy Group of the job market’s condition also reveals the divergence between the zone and the rest of the country. Regions from the Northeast, the Great Lakes and the Southeast all have seen significant job losses, and the damage is spreading to the Pacific Northwest, New York and New Jersey. In contrast, the Kansas City area and much of the zone of sanity has experienced only a ratcheting down of its generally steady growth rate. Things are not bustling, but there seem to be few signs of a basic economic collapse.

Sanity, as Whitney put it, may constitute a critical part of the equation. If you discuss why people live in a place like Kansas City, people tend to speak about stability, family-friendliness and the basic ease of everyday life. Many executives, notes Phil DeNicola, who runs Strong Suit Relocation, initially resist a transfer to the region but quickly see the advantages.

“It is attractive to be here,” notes DeNicola. “You don’t get a lot of highs and lows for years. There is stability instead, particularly for families. It all reduces your stress.”

Of course, not everyone is satisfied with the status quo. As in many second-tier urban centers, many in Kansas City’s leadership crave being something other than pleasant, affordable and stable. Leaders in the city – home to roughly one in four of the region’s 2 million residents – have been particularly exercised to show that KC can be as hip and cool as New York, L.A. or, at the very least, Chicago.

“There’s a real kind of self-loathing here,” notes Mary Cyr, a Harvard-trained architect, who works on projects throughout the region. “We feel less than what we are. We do not know what we are as a city. We don’t even realize what we have.”

Hundreds of millions have been poured and continue to pour into the usual monuments favored by urban policymakers and subsidy-hungry developers – a sparkling new arena, plans for an expanded convention center and a massive entertainment complex called the Power and Light District. Yet at the same time, the city’s budget, like many others, is severely strapped, so much so that City Hall is considering not turning on the city’s iconic fountains this spring.

Even worse, city and regional issues seem to result in plenty of money for new expressions of wannabe grandiosity. One notable example: plans to build a $700 million-plus light-rail line, the kind of thing that has become the sine qua non for the “monkey see, monkey do” school of urban policymakers across the country.

This project makes little sense in a region with a well-below-average percentage of jobs in its downtown core – roughly around 7% – with one of the lowest shares of transit-riding residents in the nation. The relative lack of traffic makes a rail system less sensible than could be argued for higher-density urban corridors, where it at least can be imagined that many would give up their cars.

Ultimately, none of this taxpayer largesse is likely to do much more than replicate the same kind of development that can be found in scores of cities – from St. Louis to Dallas – that have tried it. At best, you get a few blocks of activity but very little in terms of urban dynamism.

“The growth of downtown is not at all organic – it’s kind of forced,” notes architect Cyr. “They build all those projects in there, and you end up with the huge monumental buildings and the Gap.”

The problem for the downtown crowd is that Kansas City has remained a quintessential American city, most dynamic in places where private initiative leads the way. Typically the bulk of new growth has taken place in the suburban fringes, but there are several successful nodes within the city, particularly around the lovely, 1920s vintage, privately developed Country Club Plaza area, famous for being the world’s first modern shopping center.

Similarly, the artist-inspired Crossroads district has also evolved – largely without government help – into a genuine bastion of bohemians, with small companies and locally owned restaurants. With its low-cost commercial and residential space, as opposed to government subsidies, many see the area as precisely the kind of grass-roots urban life with a future in a place like Kansas City.

Such developments in the city, as well as outside, make it possible to project a very bright future for Kansas City – and across the zone of sanity. Unless there is a massive shift in conditions, the zone should see a return to prosperity earlier than places bogged down with excess foreclosures, shuttering industries, soaring taxes and ever-tightening regulation. Dan Whitney, for example, expects the local housing supply to run out soon – with “tremendous pent-up demand” by the end of the year. If credit conditions improve, new construction should resume within the next 18 months.

This all reflects the essential attractiveness of cites like Kansas City. Overall, in fact, its rate of domestic in-migration has been higher than much-celebrated Seattle and only slightly below that of Denver. Indeed, since 2000, Kansas City’s regional population has grown 8.6%, more than twice as much as New York, Boston, San Francisco or Los Angeles.

Unlike the national media, which rarely focus on mundane things that drive most people’s lives, some seem to get the appeal of lower prices, affordable housing options and a generally calm environment. Although never a beacon for newcomers, like Phoenix, Atlanta or Dallas, Kansas City has not suffered the massive out-migration seen in such big metropolitan regions as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago or New York.

In fact, Kansas City has enjoyed a slow but steady in-migration through the past decade. These newcomers could provide the energy, talent and initiative that a region, known for stability, needs to get to the next level. Attracting more of them – not new prestige projects or subsidized developments – remains the key to the region’s future.

Instead of trying to duplicate growth patterns that are foundering on the coasts and in countless Rust Belt cities, the denizens of the zone of sanity need to learn how to build on their virtues of stability and affordability. Particularly in hard times, such things count for much more than many – both inside and outside the region – might imagine.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History and is finishing a book on the American future.