For decades, California has epitomized America’s economic strengths: technological excellence, artistic creativity, agricultural fecundity and an intrepid entrepreneurial spirit. Yet lately California has projected a grimmer vision of a politically divided, economically stagnant state. Last week its legislature cut a deal to close its $42 billion budget deficit, but its larger problems remain.

California has returned from the dead before, most recently in the mid-1990s. But the odds that the Golden State can reinvent itself again seem long. The buffoonish current governor and a legislature divided between hysterical greens, public-employee lackeys and Neanderthal Republicans have turned the state into a fiscal laughingstock. Meanwhile, more of its middle class migrates out while a large and undereducated underclass (much of it Latino) faces dim prospects. It sometimes seems the people running the state have little feel for the very things that constitute its essence — and could allow California to reinvent itself, and the American future, once again.

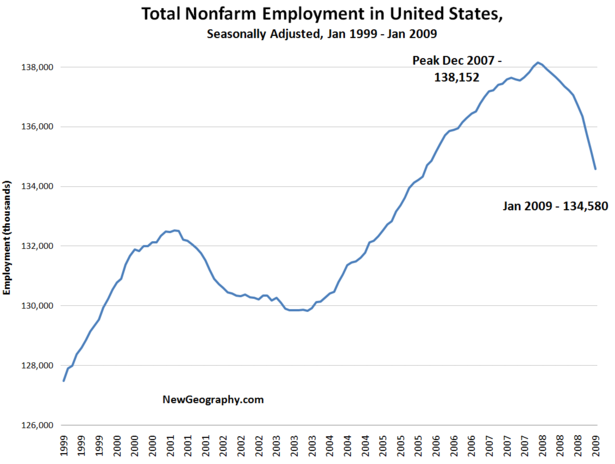

The facts at hand are pretty dreary. California entered the recession early last year, according to the Forecast Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and is expected to lag behind the nation well into 2011. Unemployment stands at roughly 10 percent, ahead only of Rust Belt basket cases like Michigan and East Coast calamity Rhode Island. Not surprisingly, people are fleeing this mounting disaster. Net outmigration has been growing every year since about 2003 and should reach well over 200,000 by 2011. This outflow would be far greater, notes demographer Wendell Cox, if not for the fact that many residents can’t sell their homes and are essentially held prisoner by their mortgages.

For Californians, this recession has been driven by different elements than the early-1990s downturn, which was largely caused by external forces. The end of the Cold War stripped away hundreds of thousands of well-paid defense-related jobs. Meanwhile, the Japanese economy went into a tailspin, leading to a massive disinvestment here. In South L.A., the huge employment losses helped create the conditions conducive to social unrest. The 1992 Rodney King verdict may have provided the match, but the kindling was dry and plentiful.

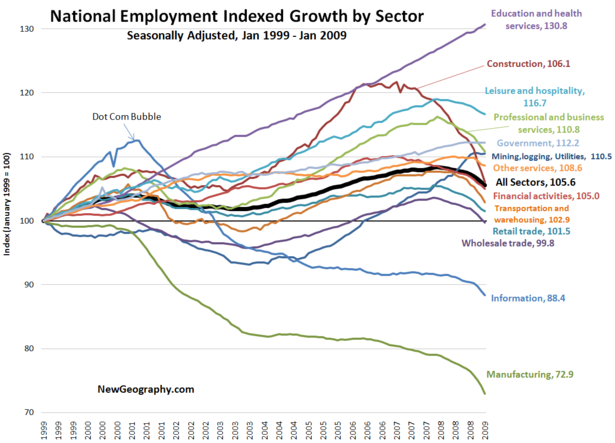

This time around, the recession feels like a self-inflicted wound, the result of “bubble dependency.” First came the dotcom bubble, centered largely in the Bay Area. The fortunes made there created an enormous surge in wealth, but by 2001 that bust had punched a huge hole in the California budget. Voters, disgusted by the legislature’s inability to cope with the crisis, recalled the governor, Gray Davis, and replaced him with a megastar B-grade actor from Austria.

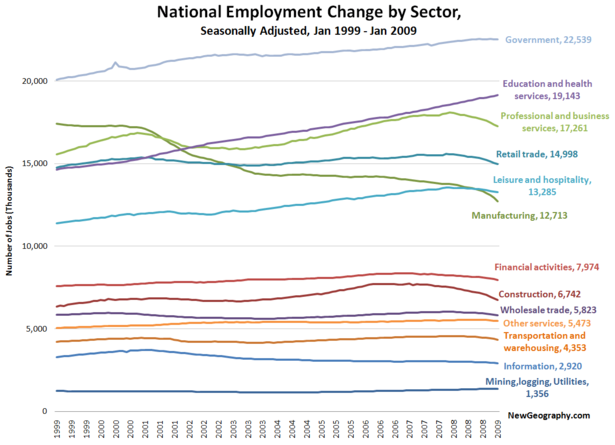

Yet almost as soon as the Internet bubble had evaporated, a new one emerged in housing. As prices soared in coastal enclaves, people fled to the periphery, often buying homes far from traditional suburban job centers. At first, it seemed like a miraculous development: people cheered as their home’s “value” increased 20 percent annually. But even against the backdrop of the national housing bubble, California soon became home to gargantuan imbalances between incomes and property prices. The state was also home to such mortgage hawkers as New Century Financial Corp., Countrywide and IndyMac. For a time the whole California economy seemed to revolve around real-estate speculation, with upwards of 50 percent of all new jobs coming from growth in fields like real estate, construction and mortgage brokering.

As a result, when the housing bubble burst, the state’s huge real-estate economy evaporated almost overnight. Both parties in the legislature and the governor failed miserably to anticipate the impending fiscal deluge they should have known was all but inevitable.

To many longtime California observers, the inability of the political, business and academic elites to adequately anticipate and address the state’s persistent problems has been a source of consternation and wonderment. In my view, the key to understanding California’s precipitous decline transcends terms like liberal or conservative, Democratic and Republican. The real culprit lies in the politics of narcissism.

California, like any gorgeously endowed person, has a natural inclination toward self-absorption. It has always been a place of unsurpassed splendor; it has inspired and attracted writers, artists, dreamers, savants and philosophers. That’s especially true of the Bay Area—ground zero for California narcissism and arguably the most attractive urban expanse on the continent; Neil Morgan in 1960 described San Francisco as “the narcissus of the West,” a place whose fundamental asset was first its own beauty, followed by its own culture of self-regard.

At first this high self-regard inspired some remarkable public achievements. California rebuilt San Francisco from the ashes of the great 1906 fire, and constructed in Los Angeles the world’s most far-reaching transit system. These achievements reached a pinnacle under Gov. Pat Brown, who in the 1960s oversaw the expansion of the freeways, the construction of new university, state- and community-college campuses, and the creation of water projects that allowed farming in dry but fertile landscapes.

Yet success also spoiled the state, incubating an ever more inward-looking form of narcissism. Even as the middle class enjoyed “the good life” — high-paying jobs, single-family homes (often with pools), vacations at the beach — there was a growing, palpable sense of threats from rising taxes, a restless youth population and a growing nonwhite demographic. One early expression of this was the late-1970s antitax movement led by Howard Jarvis. The rising cost of government was placing too much of a burden on middle-class homeowners, and the legislature refused to address the problem with reasonable reforms. The result, however, was unreasonable reform, with new and inflexible limits on property and income taxes that made holding the budget together far more difficult.

Middle-class Californians also began to feel inundated by a racial tide. This was not totally based on prejudice; Californians seemed to accept legal immigration. But millions of undocumented newcomers provoked fear that there were no limits on how many people would move into the state, filling emergency rooms with the uninsured and crowding schools with children whose parents neither spoke English nor had the time to prepare their children for school. By 1994, under Gov. Pete Wilson, the anti-immigrant narcissism fueled Proposition 187. It was now OK to deny school and medical services to people because, at the end, they looked different.

Today the politics of narcissism is most evident among “progressives.” Although the Republicans can still block massive tax increases, the predominant force in California politics lies with two groups — the gentry liberals and the public sector. The public-sector unions, once relatively poorly paid, now enjoy wages and benefits unavailable to most middle-class Californians, and do so with little regard to the fiscal and overall economic impact. Currently barely 3 percent of the state budget goes to building roads or water systems, compared with nearly 20 percent in the Pat Brown era; instead we’re funding gilt-edged pensions and lifetime guaranteed health care. It’s often a case of I’m all right, Jack — and the hell with everyone else.

The most recent ascendant group are the gentry liberals, whose base lies in the priciest precincts of San Francisco, the Silicon Valley and the west side of Los Angeles. Gentry liberalism reflects the narcissistic values of successful boomers and their offspring; their politics are all about them. In the past this was tied as much to cultural issues, like gay rights (itself a noble cause) and public support for the arts. More recently, the dominant issue revolves around environmentalism.

Green politics came early to California and for understandable reasons: protecting the resources and beauty of the nation’s loveliest landscapes. Yet in recent years, the green agenda has expanded well beyond that of the old conservationists like Theodore Roosevelt, who battled to preserve wilderness but also cared deeply about boosting productivity and living standards for the working classes. In contrast, the modern environmental movement often adopts a largely misanthropic view of humans as a “cancer” that needs to be contained. By their very nature, the greens tend to regard growth as an unalloyed evil, gobbling up resources and spewing planet-heating greenhouse gases.

You can see the effects of the gentry’s green politics up close in places like the Salinas Valley, a lovely agricultural region south of San Jose. As community leaders there have tried to construct policies to create new higher-wage jobs in the area (a project on which I’ve worked as a consultant), local progressives — largely wealthy people living on the Monterey coast — have opposed, for example, the expansion of wineries that might bring new jobs to a predominantly Latino area with persistent double-digit unemployment. As one winegrower told me last year: “They don’t want a facility that interferes with their viewshed.” For such people, the crusade against global warming makes a convenient foil in arguing against anything that might bring industrial or any other kind of middle-wage growth to the state. Greens here often speak movingly about the earth — but also about their personal redemption. They have engaged a legal and regulatory process that provides the wealthy and their progeny an opportunity to act out their desire to “make a difference” — often without real concern for the outcome. Environmentalism becomes a theater in which the privileged act out their narcissism.

It’s even more disturbing that many of the primary apostles of this kind of politics are themselves wealthy high-livers like Hollywood magnates, Silicon Valley billionaires and well-heeled politicians like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jerry Brown. They might imagine that driving a Prius or blocking a new water system or new suburban housing development serves the planet, but this usually comes at no cost to themselves or their lifestyles.

The best great hope for California’s future does not lie with the narcissists of left or right but with the newcomers, largely from abroad. These groups still appreciate the nation of opportunity and aspire to make the California — and American — Dream their own.

Of course, companies like Google and industries like Hollywood remain critical components, but both Silicon Valley and the entertainment complex are now mature, and increasingly dominated by people with access to money or the most elite educations. Neither is likely to produce large numbers of new jobs, particularly for working- and middle-class Californians.

In contrast, the newcomers, who often lack both money and education, continue in the hierarchy-breaking tradition that made California great in the first place. Many of them live and build their businesses not in places like San Francisco or West L.A., but in the increasingly multicultural suburbs on the periphery, places like the San Gabriel Valley, Riverside and Cupertino. Immigrants played a similar role in the recovery from the early-1990s doldrums. In the ’90s, for example, the number of Latino-owned businesses already was expanding at four times the rate of Anglo ones, growing from 177,000 to 440,000. Today we see signs of much the same thing, though it often involves immigrants from the Middle East, the former Soviet Union, Mexico or South Korea. One developer, Alethea Hsu, just opened a new shopping center in the San Gabriel Valley this January — and it’s fully leased. “We have a great trust in the future,” says the Cornell-trained physician.

You see some of the same thing among other California immigrants. More than three decades ago the Cardenas family started slaughtering and selling pigs grown on their two-acre farm near Corona. From there, Jesús Sr. and his wife, Luz, expanded. “We would shoot the hogs through the head and sell them off the truck,” says José, their son. “We’d sell the meat to people who liked it fresh: Filipinos, Chinese, Koreans and Hispanics…We would sell to anyone.” Their first store, predominantly a carnicería, or meat shop, took advantage of the soaring Latino population. By 2008, they had 20 stores with more than $400 million in sales. In 2005 they started to produce Mexican food, including some inspired by Luz’s recipes to distribute through such chains as Costco. Mexican food, notes Jesús Jr., is no longer a niche. “It’s a crossover product now.”

Despite the current mess in Sacramento, this suggests some hope for the future. Perhaps the gubernatorial candidacy of Silicon Valley folks like former eBay CEO Meg Whitman (a Republican), or her former eBay employee Steve Wesley (a Democrat), could bring some degree of competence and common sense to the farce now taking place in Sacramento. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who’s said to be considering the race, would also be preferable to a green zealot like Jerry Brown or empty suits like Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa or San Francisco’s Gavin Newsom.

But if I am looking for hope and inspiration, for California or the country, I would look first and foremost at people like the Cardenas family. They create jobs for people who didn’t go to Stanford or whose parents lack a trust fund. They constitute what any place needs to survive: risk takers who are self-confident but rarely selfish. These are people who look at the future, not in the mirror.

This article originally appeared at Newsweek.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History and is finishing a book on the American future.

and is finishing a book on the American future.