Ordos, in China’s Autonomous Region of Inner Mongolia (equivalent to a province) has received international notoriety as a "ghost city." I had already visited one other ghost city and found the reports considerably exaggerated (The Zhengzhou New Area in Henan, a commercial and residential district). But Ordos has received by far the most publicity.

It turns out that in reality the people far outnumber the ghosts, something I should have recognized when it was difficult to find a hotel room six months before my visit. Ghosts do not generally need hotel rooms. But the ghost city label is an exaggeration.

Defining Ordos

What is Ordos? Ordos (E’erduosi) is one of the more than 300 municipality level jurisdictions that constitute China and cover virtually all of its land area. Like other municipalities, Ordos is divided into districts which are translated broadly as county level jurisdictions. China has about 2,900 county level jurisdictions, compared to the 3,100 county level jurisdictions in the United States. There is an important difference, however. In the United States, with a few exceptions, municipalities are within counties and there may be many municipalities within counties. In China, counties are within municipalities.

Ordos is one of 12 municipalities in Inner Mongolia. Ordos is composed of eight districts. The Ordos metropolitan area is located in the urban district of Dongsheng and the "banner" (Inner Mongolian title for county) of Ejin Horo (the urbanized part of which is Azhen). The Kangbashi new area, to which the ghost city stories refer, is split between Dongsheng and Ejin Horo.

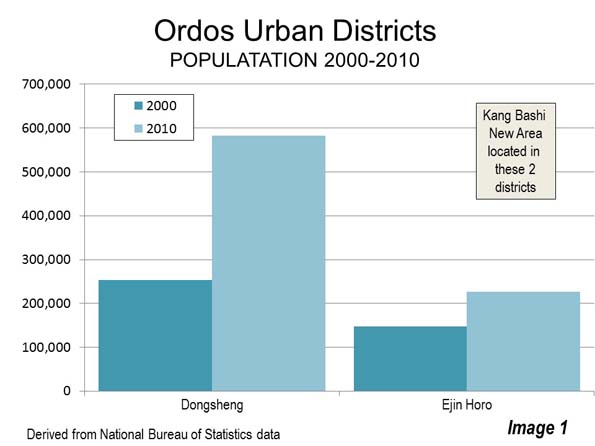

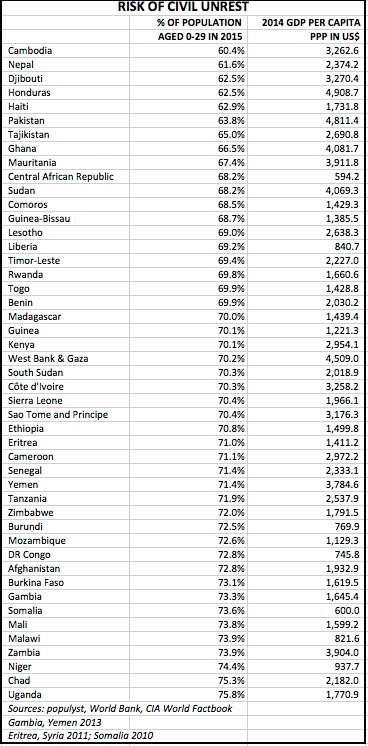

Contrary to the “ghost city” meme, population growth has been strong in these two districts. In Dongsheng, the 2010 census counted approximately 580,000 residents, an increase of 130 percent over the 2000 census. The population of Ejin Horo rose 53 percent to approximately 225,000 residents. Overall, these two adjacent districts represent a labor market (metropolitan area) of nearly 810,000 residents, which grew more than 100 percent between 2000 and 2010 (Image 1).

Ordos is located in the northern half of the Ordos Loop of the Yellow River, which with the Yangtze is one of China’s two great rivers. After passing Lanzhou (capital of Gansu), the eastward flowing river takes a sharp left turn to the north for approximately 600 kilometers (375 miles), then a sharp right turn back to the east for 300 kilometers (200 miles), turning south for 600 kilometers and finally turning east toward the Yellow Sea.

Overall, the population of Ordos was approximately 1.94 million in the 2000 census and had grown 42 percent since 2000. As a result, Ordos was by far the fastest growing of the 12 municipalities in Inner Mongolia. The municipality grew at more than double the rate of the capital, Hohhot (Huhehaote), and approximately seven times the overall rate of Inner Mongolia. The growth rate of Ordos was also five times China’s national 10 year growth rate of 7.8 percent.

The municipality covers a land area of 87,000 square kilometers, somewhat larger than Austria. Ordos Most of the population is in the more rural districts.

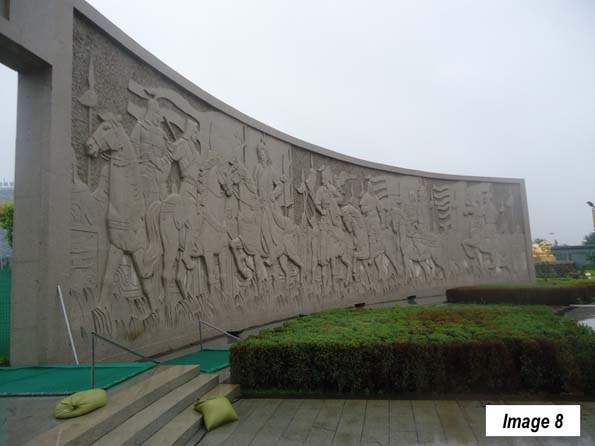

Genghis Khan

Genghis Kahn, founder of the Mongol empire (13th century), history’s largest contiguous empire plays importantly in the history of Ordos. Genghis Kahn is reputed to have been so impressed by Ordos that he wanted his personal effects buried here. The effects are buried at a mausoleum approximately 10 miles (25 kilometers) south of Kangbashi. The actual burial place of Genghis Kahn is not known, and consistent with Mongol tradition, is secret.

The So-Called "Ghost City:" Kangbashi New Area

The part of Ordos to which the "Ghost City" stories have referred is the Kangbashi New Area. It is adjacent to and north of the urbanization of Azhen in Ejin Horo. The Kangbashi new area covers approximately 350 square kilometers (135 square miles) in the Dongsheng and Ejin Horo districts at the time of the 2010 census. Thus, a census population count is not readily available. Informal estimates placed the population at under 30,000 in 2010. A more recent informal estimate by an Ordos municipal official indicated that the registered population had reached 72,000 in 2012 and would soon rise to 100,000.

Development of the Kangbashi New Area

Ordos is one of the most affluent municipalities of China. It is comparatively new wealth, which is the result of vast coal reserves that have been increasingly called upon since 2000 to support China’s spectacular growth. . According to People’s Daily, by 2012 the gross domestic product per capita of Ordos exceeded that of both Spain and South Korea.

With the huge natural resource revenue gains, municipal officials decided to build a new city approximately 16 miles (25 kilometers) south of the municipal seat in Dongsheng. In 2006, the municipal seat was moved from Dongsheng to the Kangbashi new area. Both the Kangbashi New Area and Ejin Horo are within commuting distance of much larger Dongsheng, via the Dongsheng Expressway. As of 2012, the municipality indicated that at least one half of the municipal functions had been moved to Kangbashi.

The Ordos Ceremonial Mall

Some national governments in the world have built new capital cities or districts and taken the opportunity to order them around what might be called ceremonial malls — government buildings, monuments and cultural institutions arranged around a central axis. Governments that build new capital cities have unique opportunities to build ceremonial malls. Perhaps the first of these was Washington, with its Capitol Mall (The Supreme Court to the Lincoln Memorial) and the later developed mall from the White House to the Jefferson Memorial.

Other particularly notable examples are Delhi, Canberra and Brasília. Perhaps the most famous such mall, though without the adjacent buildings and memorials, which had already been built elsewhere, is The Mall, running from Buckingham Palace to Trafalgar Square in London. This mall is somewhat different than the others, because it was built after most of the government buildings, which are located elsewhere.

Ceremonial malls can be built by local governments as well, and Ordos has built one of world-class dimensions. The table below compares the Ordos mall with other representative government malls. With a length of 2.7 miles (4.3 kilometers), the Ordos mall is approximately the equal of Washington’s Capitol Mall and Canberra’s middle mall, (Federation Mall/ANZAC Parade). The Ordos mall is somewhat shorter than the Delhi mall and less than one half the length of the Brasília mall, parts of which remain undeveloped. The Ordos mall is more than twice as long as The Mall in London.

The Ordos mall is more extensive, for example, than what may be the largest local government mall in the United States, in Los Angeles. This mall is shared by the city and the county of Los Angeles, with more than five times as many residents. In fact, the Ordos mall is of sufficient expanse and design to be mistaken for the centerpiece of a newly built national capital.

In short, the Ordos mall is world class and already attracting tourists, principally from around China. As with the rest of China, international tourism is in its infancy and holds great potential for growth.

| Selected Ceremonial Malls |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dimensions (KM) |

Dimensions (Miles) |

|

|

| Location |

Length |

Axis Width |

Length |

Axis Width |

Government |

Population (Millions) |

| Brasilia |

9.7 |

0.21 |

6.0 |

0.13 |

National |

195 |

| Delhi |

5.2 |

0.24 |

3.2 |

0.15 |

National |

1225 |

| Washington (Capitol Mall) |

4.3 |

0.50 |

2.7 |

0.31 |

National |

310 |

| Ordos |

4.3 |

0.18 |

2.7 |

0.11 |

Local |

2 |

| Canberra (Federation Mall/ANZAC Parade) |

4.3 |

0.03 |

2.7 |

0.02 |

National |

22 |

| London (The Mall) |

1.3 |

0.06 |

0.8 |

0.04 |

National |

62 |

| Los Angeles |

1.1 |

0.08 |

0.7 |

0.05 |

Local |

10 |

| Axis width is minimum central area around which buildings and monuments are organized |

|

| Canberra & Washington have more than one mall |

|

|

|

|

|

| Some of Brasilia mall is undeveloped |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Touring the Ordos Mall

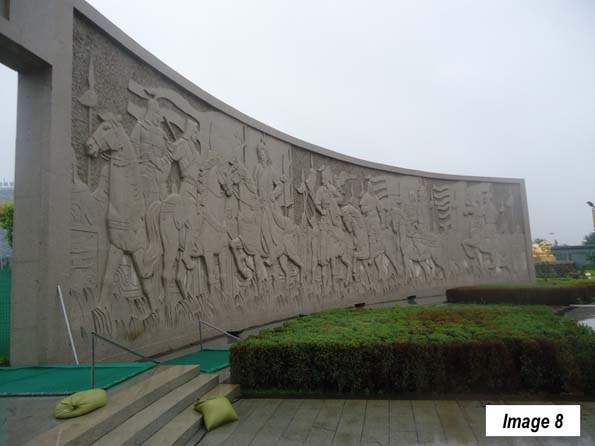

The core of the mall is an axis, one large block wide, composed of greenery and statues (Images 2-13).

The mall stretches from municipal buildings at the north (Image 2) to a lake (Image 3), across which are skyscrapers, anchoring the mall on the south (Images 4 and 13). This interruption by a lake is similar to the Canberra mall described above

Near the north end of the mall is the Genghis Khan statue (Image 5).

The two horse’s statue is in the square to the south of the Genghis Khan statue (Image 6).

Each side of the mall is defined by one-way streets that are four lanes wide.

Among the two most important government buildings on the mall are the Library of Ordos and the Ordos Museum (to the left and right, respectively, in Image 9). Neither of these buildings will be pleasing to aficionados of traditional architecture, including the author. I agree with Chinese President Xi, who suggested that China needed no more weird buildings, referring to the CCTV Tower in Beijing, which local taxi drivers told me is referred to as the "underpants" building. Of course, architecture is a matter of taste.

Across the mall is the Ordos National Theatre and the Ordos Culture and Arts Center (Image 10, left and right). The circular and curved lines of these buildings offer a welcome refuge from the more courageous architecture of the Library and Museum, in the author’s view.

The mall also includes commercial buildings (Image 11). These buildings include a wide array of retail stores, such as large electronic and home appliance outlets, banks and other facilities. Within a one block walk of my hotel there were at least seven restaurants from which to choose. Generally, ghosts do not require this density of eating establishments.

Residential Areas

There are a variety of residential areas surrounding the mall on three sides (the south end of the mall is bordered by the urbanization of Ejin Horo). The residential buildings tend to be from 5 to 12 floors (Images 14 – 16), and include the equivalent of strip malls (Image 16) that are close at hand for residents and can have full parking lots. The residential areas also include some monumental treatments (Image 17).

Outside the Built-Up Urban Area

The built-up area of Kangbashi is relatively small, covering less than 10 square miles (25 square kilometers), or less than 10 percent of the Kangbashi new area.

Most of the "Ghost City" articles to limit their coverage to the small developed area. With the exception of a major roadway skeleton (along which there is virtually no development in many areas), much of the Kangbashi New Area is not a city at all. There are some small pockets of residential development spread throughout the area and a number of government buildings similarly dispersed beyond the built-up area (Images 18-24). At the same time, the parking lots were far from empty.

There are also a number of religious sites outside the built up urban area (Images 22 & 23) and three similarly designed sports facilities (Image 24).

The traffic volumes are well below the capacity of the more than ample arterial street system. But this is not unusual for newer suburban areas in China, where eight lane streets can be the rule.

What About the People?

Much of the ghost city coverage has been based on an assumption that few if any residents have arrived. A number of articles point out that the present development has been built for 300,000 residents and that the population is much less (above). Yet, the municipality indicates that the 300,000 resident projection is for 2020. Whether or not Ordos will reach that population by 2020 cannot yet be known.

Some of the ghost city articles have claimed that the Kangbashi new area was projected to have 1 million residents. However, the municipality’s website indicates that the 1,000,000 vision was for a much larger area than the Kangbashi new area. It also included Dongsheng, which alone already has nearly 600,000 residents as well as the urbanization of Ejin Horo. In other words, under the plan the area was already well on its way to achieving the eventual projection.

Other articles point out that there are few people walking on the streets. But, as Chai Jiliang, chief publicity officer of Kangbashi told China Daily in 2012: "So, why do local residents who mostly own private cars and have convenient public transportation have to walk on the streets if there are no major public events?" There is further evidence of people, the establishment of a campus of the Beijing Normal University in the Kangbashi new area. Indeed a recent article in The New York Times Style Magazine, by Jody Rosen, reported not only that there were people in the Kangbashi new area, but that they were generally happy with their city.

Ejin Horo

Perhaps the biggest surprise was the Ejin Horo urbanization (Azhen), immediately to the south of the Kangbashi New Area (Images 25-27). The tallest buildings are here and some of the most impressive commercial architecture. Just across the principal bridge from the Kangbashi New Area are two buildings resembling the One World Wide Tower on Eighth Avenue in New York (Image 25). Ejin Horo also has many condominium towers that are often taller than those in the Kangbashi New Area. Unlike the Kangbashi New Area, Ejin Horo appears to have grown more organically in response to market demand. The area’s international airport is also located in Ejin Horo.

Big Dreams, Big Challenges

The Kangbashi new area does face some problems. Like the rest of China, there are a number of uncompleted building projects, as the economy is not growing nearly as quickly as before. Though, again, I expected many more based on the negative published reports.

There has been a severe reduction in house prices, as the Chinese economy has gotten worse. There are reports that many of the apartments and condominiums are empty, though no information was found on the extent of unsold houses or the number that have been purchased simply as investments to hold (and have no residents). It is not unusual for Chinese buyers to invest in additional properties, leaving them empty, a situation that is also been reported in central Vancouver. However, there was no lack of cars in the parking lots of the residential districts.

Peoples Daily reports that coal extraction volumes are down significantly, which when combined with substantially lower coal prices in recent years has cut severely into the revenues of the Ordos municipality. The municipality is seeking additional revenue enhancing strategies, such as tourism (there are 9 million tourists annually), automobile manufacturing and solar power facilities.

Liu Qiang, a People’s Daily columnist noted that "There are worries that Ordos, with its huge debts and years of mismanagement, will repeat Detroit’s road to bankruptcy," While noting that Chinese municipalities are not permitted to file bankruptcy, the columnist suggests that " China’s local government debt, if not being better managed, might potentially pose a systematic risk greater than in Detroit."

Big dreams are not limited to cities in China. Ordos may have built civic monuments and infrastructure beyond its means. Only time will tell whether such visions can be sustained. The reality, however, is that Ordos, including the Kangbashi new area, is surprisingly vibrant and functioning with real people.

Note 1: Inner Mongolia is a part of China. Mongolia (often called "Outer Mongolia) is an independent nation located between China and Russia.

Note 2: The Evolving Urban Form is a newgeography.com metropolitan and urban area profiles from around the world. The more than 50 articles on in the series can be accessed here.

Photo: Genghis Kahn Mausoleum, Ordos, Inner Mongolia, China by Fanghong (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.