A reader comment on a feature by John Sanphillipo (“Finally! Great New Affordable Bay Area Housing! Caught my eye.”). The comment ("You shouldn’t have to go to Nashville") expressed an understandable frustration about the sad reality that firms leaving coastal California often skip right over the Central Valley “where the housing costs are reasonable, there are some lovely old homes on tree lined streets, the humidity is less, the mountains are nearby, and you can drive there in 2-3 hours rather than fly.”

Would that it were true. In fact, as this article will show, housing costs are anything but reasonable, given the median income, in the Central Valley, which along with the rest of the non-coastal portion of the state, will be referred to as Outer California in this article.

California Housing Affordability: Into the Abyss

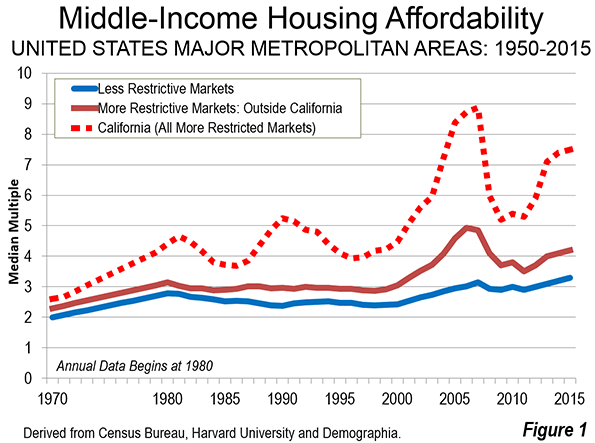

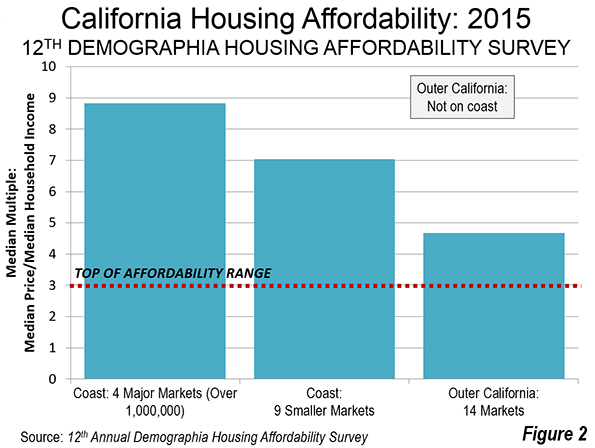

California’s severely unaffordable housing is legendary, having escalated from approximately the average national price to income ratio in 1970. This is most evident in the four largest coastal metropolitan areas, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and San Jose. Out of the 87 major markets (over 1 million population) in nine nations, these markets ranked fourth, seventh and in a ninth place tie for the least affordable 8n the 12th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey. Their median multiples (median house price divided by median household income) required from 8.1 to 9.8 years income to purchase the median priced house. This compares to the affordability of these and other California markets which had median multiples of approximately 3.0 or less in 1970 and in prior years (Figure 1).

The housing unaffordability of these markets, with an average median multiple of 8.8 is rivaled by the smaller coastal markets (such as Monterey County, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara and Ventura County), with their median multiple of 7.0. Both market categories are rated as severely unaffordable. But housing has become seriously unaffordable even in Outer California, where the average median multiple is 4.7(Figure 2). House prices have been escalating relative to incomes in Outer California since the housing bust, before which their housing affordability was even worse than now (below).

Housing Affordability in Outer California

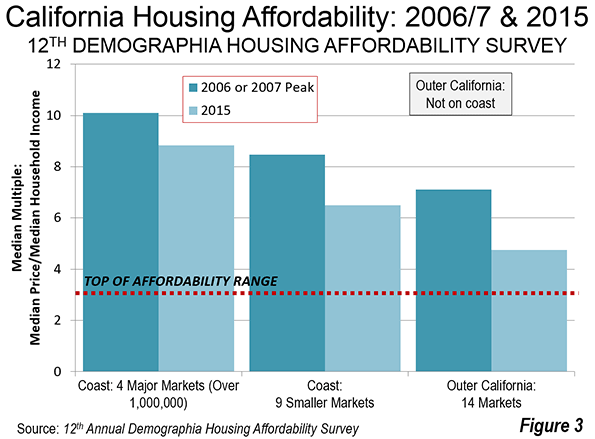

A few examples will make the point. Riverside-San Bernardino, and exurban metropolitan area adjacent to Los Angeles had a severely unaffordable median multiple of 5.2 in 2015. Sacramento, had a seriously unaffordable median multiple of 4.7. Both of these major metropolitan areas reached far higher median multiples in the run-up to the housing bust, with Riverside San Bernardino reaching 7.6 and Sacramento reaching 6.6.

But the problem is by no means limited to the largest metropolitan areas. Stockton, now officially a part of the larger San Jose-San Francisco combined statistical area as a result of a housing cost driven exodus of commuters from the Bay Area has a severely unaffordable median multiple of 5.3. Things were much worse in the run-up to the bust, at 8.6. Even long depressed Fresno, far from either the Bay Area or Los Angeles, is nearing severe unaffordability, with a median multiple of 5.0 and reached 7.2 during the bubble. More remote Chico, one of the smallest US markets in the Demographia survey also has a median multiple of 5.0 (see Central Valley map at the top).

Modesto, a 2020 candidate for addition to the San Jose – San Francisco combined statistical area due to the overspill of households seeking houses they can afford, also has a seriously unaffordable median multiple of 4.5. Modesto reached 7.6 during the bubble.

Among the 29 markets rated in California, the most affordable was Bakersfield, which in a few years is likely to follow Fresno into the over 1 million category. During the bubble, Bakersfield reached a median multiple of 6.6. Small town Visalia, nestled against the Sierra foothills, tied Bakersfield’s most affordable 4.3 median multiple, and reached an astounding 5.8 during the bubble. Hanford also tied for the most affordable.

The comparison to the bubble peaks is particularly important because it illustrates the volatility of housing markets. Even in small markets, house prices are prone to explode when demand exceeds supply, due in large part to land use regulatory and environmental law structure that restricts housing even in more remote areas, driving prices up (See William A. Fischel, Regulatory Takings). Figure 3 shows that California house prices in each of the three geographic categories were even more unaffordable during the bubble than today.

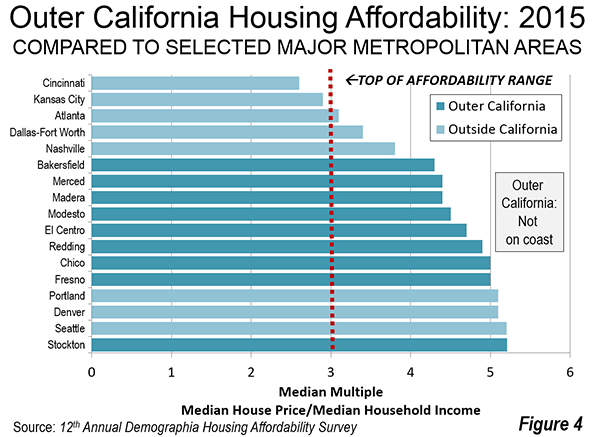

Even at their current housing affordability levels, the housing markets of Outer California are considerably overpriced. This is indicated by Figure 2, which compares the median multiples in Stockton, Fresno, Bakersfield, Modesto, Redding, Chico, Merced, Madera and the Imperial Valley’s El Centro with severely unaffordable and overregulated Portland, Seattle and Denver, as well as Nashville and other major markets that are more affordable than any in California (Figure 4).

Indeed, out of the 231 US markets in the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, the 27 California markets represent nearly half of the 58 most expensive.

Meanwhile, a recent report by Zumper indicated among the 50 largest municipalities in the nation, four of the most expensive seven are also in California, with the city of San Francisco ranked number one, followed San Jose at third, the city of Oakland at fifth and the city of Los Angeles at seventh. Eight of the most expensive municipalities out of the 100 largest are also in California, such as Palo Alto in the Bay Area, Coronado in the San Diego area and Santa Monica in the Los Angeles area.

As if the regulatory and legal structure that combined with the artificially higher demand from loose lending policies were not enough, barely a decade later California is in the process of implementing one of the most radical land-use regulatory structure in a liberal democracy. It will be far more difficult in many areas to build the detached housing that is been the mainstay of the state, which already has the highest urban population density in the nation (see: “California declares war on suburbia"). This suggests that housing affordability is likely to worsen further.

There is good reason for a both companies and middle income households to stay away from or leave California.

More than Housing Affordability

But people and businesses are moving to places like Nashville for reasons other than housing affordability. The state could hardly make it more clear that most business is not welcome. For at least 10 years, CEO Magazine has rated California as having the least favorable business climate. With competition like Illinois, Connecticut and New Jersey, to be ranked 50th with such regularity is a notable underachievement.

Data recently released by the California Manufacturers & Technology Association (CMTA) indicated that California ranked last among the states in per capita attraction of manufacturing investments in 2015. Corporate relocation specialist Joseph Vranich continues to add to a long but for California unfortunate list of companies and jobs that have recently left the state (see: "California companies had for greatness – out of California).

Of course, California is a beautiful place with one of the best climates in the world. But millions of people and many companies have found greener pastures in Nashville, Austin, Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, Charlotte, Atlanta and elsewhere. People will continue to visit, but the exodus is likely to continue.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Map of Central Valley (Sacramento Valley to the north, San Joaquin Valley to the south) courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey