Following up on the Pew study that found many states will face declining work age populations in the future, I want to highlight a recent Atlantic article called “The Graying of Rural America.” It’s a profile of the small Oregon town of Fossil, which is slowly dying as the young people leave and a rump population of older people – median age 56 – begin to pass on.

Like the Pew study, this one has implications that weren’t fully traced out.

There’s a lot of urban triumphalism these days, as cities crow about Millennials wanting to live downtown and such.

But the dirty little secret is that a lot of these places have been growing their youth populations by hoovering up the children of their hinterlands. To the extent that urban population growth is dependent on intrastate migration in these states with declining working age populations, at some point there are just plain going to be a lot fewer youngster to move to the big city. That will start to crimp urban population dynamics.

Indianapolis is a poster-child for this. About 95% of the metro area’s net migration has come from elsewhere in the state of Indiana since 2000, according to IRS tax return data.

Looking at the future, about half of the states counties (49 out of 92) are projected to actually lose population by 2050. Here’s the map from the Indiana Business Research Center.

Projected population change in Indiana counties, 2010-2050. Source: Indiana Business Research Center

The entire state is only projected to add 100,000 15-44 year olds by 2050. Even if 100% of them, or even more than 100% of them, are in Indianapolis, this still implies a fairly modest growth rate.

Given the projected demographics of its migration shed, we should expect Indianapolis to start seeing a falloff in migration. In fact, we are already seeing it. Indy was previously the Midwest champ in net domestic in-migration, but recent Census Bureau estimates show a fall-off.

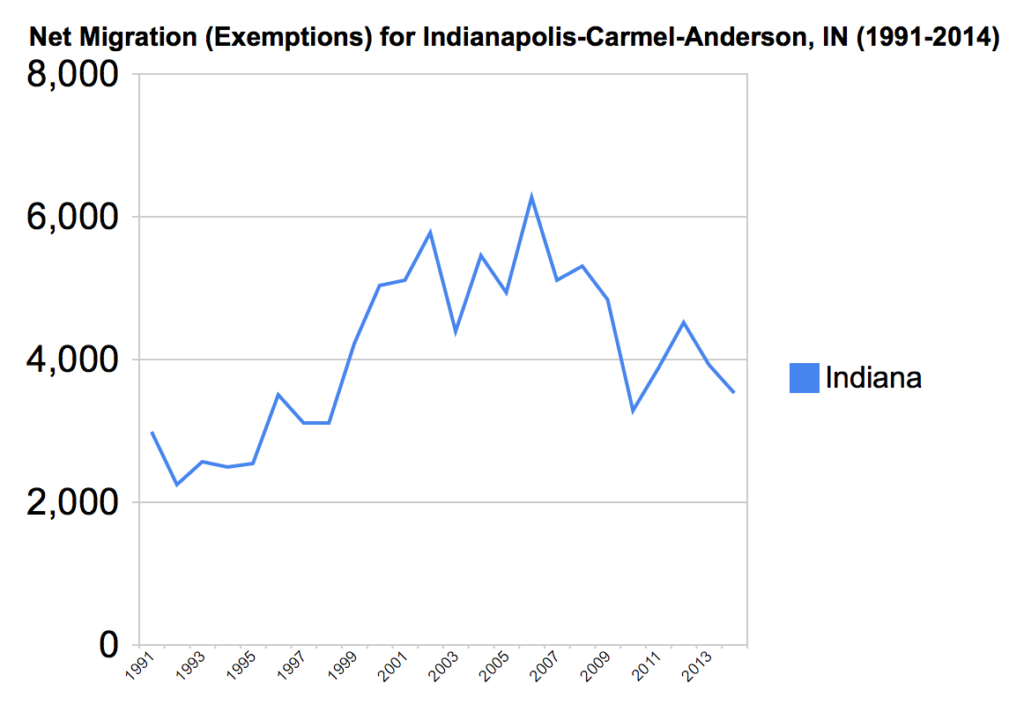

Here’s what the IRS migration data says about net migration into Indy metro from the rest of the state.

Net migration into metro Indianapolis from the rest of the state, 1991-2014. Source: Aaron Renn analysis of IRS county to county migration data

There was a spike up starting around 1997, the dawn of the dotcom era. This more or less corresponded with the rise of the city talk. (Richard Florida’s Rise of the Creative Class came out in 2002).

During the 2000s, Indianapolis was the Midwest growth champ, and killed it on net domestic migration. This graph helps explain why.

But starting around 2010, inbound migration from the rest of the state has fallen off. I don’t want to claim this is entirely demographic related. Migration declined nationally during the Great Recession. And there were some methodology tweaks in this data during that time. But we can see already in the numbers what happens to metro growth if migration from the rest of the state slows down.

At some point, the decline of rural and small manufacturing counties is going to have to show up in the migration numbers to cities like Indy. Other cities that draw primarily from a national base – like Nashville or Dallas – will be less affected.

But cities that are dependent on a regional migration shed need to start doing the math on how the decline of their hinterlands will affect them.

The collapse of rural and small manufacturing economies may have been good for cities in the short term, but those cities might discover down the road that they ended up eating their seed corn.

Aaron M. Renn is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a contributing editor of City Journal, and an economic development columnist for Governing magazine. He focuses on ways to help America’s cities thrive in an ever more complex, competitive, globalized, and diverse twenty-first century. During Renn’s 15-year career in management and technology consulting, he was a partner at Accenture and held several technology strategy roles and directed multimillion-dollar global technology implementations. He has contributed to The Guardian, Forbes.com, and numerous other publications. Renn holds a B.S. from Indiana University, where he coauthored an early social-networking platform in 1991.