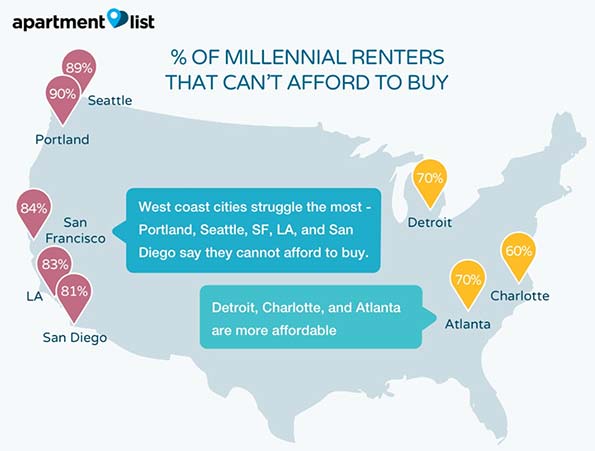

Millennial renters overwhelmingly plan on buying their own homes, though affording them could be far more challenging than they think. This is an important conclusion from a renters’ survey by apartmentlist.com, an apartment search website (See: The Affordability Crisis: Are Millennials Destined to be Renters?). Apartmentlist.com matched results from its own survey of prospective renters that visit its site with housing market data from more than 90 metropolitan areas around the country, The most revealing finding: Millennials intend to purchase their own homes, but that housing affordability is the greatest barrier. According to apartmentlist.com, the problem is the greatest on the West Coast, New York and Miami (See Figure “% of Millennial Renters that Can’t Afford to Buy”, from apartmentlist.com):

In nearly all the metros we looked at, affordability was the #1 reason for delaying homeownership, but millennials on the west coast struggled the most: Portland, San Diego, Seattle, Los Angeles, and San Francisco all had more than 80% of renters listing affordability as a concern. Miami and New York, expensive metros with many cost-burdened renters, were #6 and #7 on the list.

Perhaps surprisingly, two metropolitan areas that have been among the greatest beneficiaries of the housing affordability driven net domestic migration from coastal California, Portland and Seattle, scored the worst on affordability as a barrier to purchasing homes (90 percent and 89 percent respectively). These areas were once much less expensive in the past, but are rapidly catching up with California in terms of unaffordability.

The Preference for Home Ownership

The apartmentlist.com survey found that 79 percent of Millennials eventually plan to become home or apartment owners, while only six percent expect to rent for their whole lives. The balance (15 percent) are not sure. This 79 percent preference for home ownership is well above the current homeownership rate of approximately 64 percent.

The preference for home ownership was pervasive in the apartmentlist.com data. Among the 50 metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population, none scored below two thirds (67 percent) in Millennial home ownership preference. This is, again, above the national home ownership rate. The lowest home ownership preference among these was in Las Vegas. The highest preference for home ownership was in Rochester, at 94 percent. Charlotte and Salt Lake City also scored a 90 percent home ownership preference.

Millennials indicated a strong preference for home ownership even in metropolitan areas that have depressed home ownership rates. In 2015, Los Angeles had the lowest home ownership rate of any major metropolitan area, at 49 percent, yet 76 percent of the area’s Millennials intend to own their own homes. In New York, with only a 50 percent homeownership rate, 74 percent of Millennials plan on buying their own homes. In San Jose, with only a 51 percent home ownership rate, 74 percent of Millennials aspire to buy their own homes. In San Diego, the home ownership rate was 52 percent, yet the interest in home ownership was half-again higher (78 percent). In San Francisco, where the home ownership rate is 56 percent, 76 percent expressed an interest in owning their own homes (home ownership rates calculated from Census Bureau quarterly data from 2015).

The story is the same in the metropolitan areas often characterized as magnets for Millennial migration. In Portland and Denver, 81 percent of Millennials anticipate owning their own homes. Boston (78 percent), Seattle (77 percent) and Minneapolis-St. Paul (77 percent) are not far behind.

Saving for Decades

This data suggests that many Millennials could need to relocate to afford their own homes. The really innovative contribution of the apartmentlist.com research is as estimate of how long it will take the average Millennial to save enough money for a down payment on a starter home, which according to Trulia, is generally defined as the lower third of the market.

Apartmentlist.com develops an estimate for each metropolitan area, using monthly savings rates, existing savings and the potential for financial assistance (for example from relatives) in obtaining enough for the down payment. In the most costly market, San Francisco, the average Millennial will need more than 28 years to build up enough funding for a down payment in San Francisco. This means that older Millennials would be old enough (62) to qualify for early retirement benefits from Social Security by the time they have enough to pay the down payment on a starter home. Sacramento is nearly as challenging, where it would take another 27 years to accumulate a down payment. Things are not that much better in Los Angeles (20 years), San Diego (19 years) and Denver (18 years).

Optimistic Expectations and Disappointment

But the most important bottom line conclusion of the research is what apartmentlist.com calls the “affordability gap.” This is the difference between the actual time required to accumulate a down payment and the time expected by survey respondents. The biggest affordability gap is in San Francisco, where respondents expected down payment requirements that would take only 11 years more to save. The reality, according to the study, is 28 years, more than 2.5 times that figure. In Sacramento, respondents expected that it would take 16 years, still far short of the more realistic 27 years. In Los Angeles, San Diego and Denver, it is likely to take from eight to ten years more to save enough for a down payment than survey respondents estimate.

Setting up for More Domestic Migration

In contrast, in a number of other metropolitan areas, such as Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Atlanta, Philadelphia and Kansas City, Millennials have over-estimated the size of down payments necessary to enter the housing market.

For some time, domestic migration trends in the United States has been principally about moving from more expensive metropolitan areas to less expensive metropolitan areas. The apartmentlist.com data suggests that this trend could continue. To achieve their dreams of home ownership and to avoid a life of renting, many Millennials may move to places where housing is priced more for livability.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo by Bigstockphoto.com.