Headlines were recently made recently as Japan finally experienced a long predicted official decline in population. This is widely expected to be the beginning of a long decline in population, which the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research has projected will drop Japan’s population from its present 127 million to 43 million by 2100 (Chart). This loss equals or exceeds the population of all but 15 of the world’s nearly 200 nations, including Germany, the United Kingdom and France.

Population projections are, of course, not an exact science. They can be accurate, or they can “miss by a mile.” The preliminary 2015 census figures indicate that the population loss since 2010 has been considerably less than predicted. Japan lost 950,000 residents since between 2010 and 2015,The previous 5-year census period had shown a gain of 280,000. Losing nearly a million population is a big deal. But losing 1.5 million would have been an even bigger deal, as had been projected by Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. Over the past five years, Japan’s population loss was more than one-third less than expected (35 percent).

The big question is “why?” The most obvious answer is a combination of factors, such as more births than projected or a falling death rate. The Japanese enjoy long lives. In 2013, there were more people aged 100 or above than in the United States, despite, Japan’s 60 percent lower population. More than one in eight of the world’s centenarians live in Japan, while only one in sixty of the world’s people is Japanese.

No analysis has been identified, nor is the detailed age data for such an analysis readily available. This is to be expected this soon after publication of the first census results. However, recent media reports indicate a continuing annual decline in births. The difference could also be the result of problems in the projection methodology.

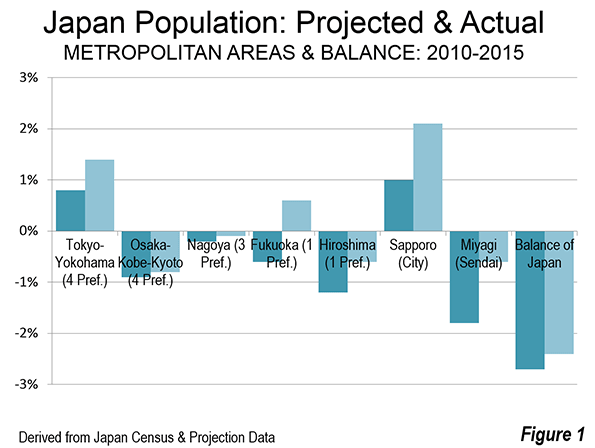

Actual and Projected Population by Area

As had been the case in the last census period (2005-2010) Tokyo was the big winner. Tokyo prefecture (note), which contains the 23 ku (cities) that constituted the city of Tokyo until its mid-1940s dissolution as well as suburbs, was expected to gain 190,000 residents, but added 355,000. Overall, the four-prefecture area of Tokyo-Yokohama, which includes Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba prefectures added more than 500,000 residents, compared to the expected 275,000. The gain in Tokyo-Yokohama was 1.4 percent, nearly double the 0.8 percent expected.

The other two megacities (over 10 million population) did not do so well. Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto (Osaka, Hyogo, Kyoto and Nara prefectures), which is larger than the Los Angeles-Riverside combined statistical area, lost 140,000 residents, nearly as many as the 164,000 projected. Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto was expected to lose 0.9 percent of its population, and nearly equaled that, at minus 0.8 percent.

Nagoya, including the prefectures of Aichi, Mie and Gifu, lost 13,000 residents, two-thirds the 19,000 projected. Nagoya lost 0.1 percent of its population, slightly better than the minus 0.2 percent projected.

The middle-sized metropolitan areas did better. The prefecture of Fukuoka, which includes the nation’s fourth largest metropolitan area, Fukuoka-Kitakyushu was expected to lose 0.5 percent of its population, Instead it managed a 0.5 percent gain. Hiroshima was expected to lose 1.2 percent of its population and lost only one-half that much (minus 0.6 percent).

The city of Sapporo, in Hokkaido prefecture, was a big winner more than doubling its projected 1.0 percent increase (Note 2). Sapporo had a population gain of 2.1 percent. Most of the Sapporo metropolitan area is in the city of Sapporo, and unlike many core municipalities, there is still room for greenfield development.

Sendai, in Miyagi prefecture was particularly hard hit by the great earthquake and tsunami of 2011. That makes Sendai’s population performance all the more impressive. Sendai was projected to suffer a population loss of 1.8 percent. Yet, its population loss was two thirds less, at 0.6 percent.

The balance of the nation even did better than expected. Outside the metropolitan areas listed above (and the city of Sapporo), Japan was expected to lose 2.7 percent of its population. The loss was somewhat more modest, at 2.4 percent.

Government Concern

Despite the better news out of the census, the government is taking the longer term population loss very seriously. Its Committee for the Future indicates that the prospect could be: “…impose a great burden on people that offsets economic growth, threatening to decrease the actual per-capita consumption level, or the metric for the actual quality and level of people’s lives.”

Even Tokyo, which has escaped the effects of population decline will be at risk, according to the Committee: The Tokyo Metropolitan area, while unable to avoid the effects of hyper-aging, will lose the vitality of a global city…”

The changing demographics are already evident in a near majority single person household population in the core Tokyo prefecture. In 2010, 46 percent of Tokyo prefecture households are single person, compared to just 32 percent at the national level, and 36 percent in Osaka prefecture, which has the second highest percentage, according to National Institute of Population and Social Security Research data. Moreover, Tokyo prefecture’s average household size, at 2.03 in 2010, was the lowest, by far in the nation, and well below the national average of 2.42. Like many core areas in the largest metropolitan areas around the world, Tokyo prefecture, less than the normal proportion of children is to be found.

The government has established a goal of increasing the fertility rate from the present 1.4 (children per woman of child-bearing age) to 1.80 by 2030 and 2.07 by 2040. This would mean a population of 102 million in 2060, compared to the 87 million that current trends suggest. This would also eventually stabilize at around 90 million, more than double the presently projected figure of 43 million.

Proposed government strategies have involved an array from expanding the use of paternity leave, making it easier for women to retain their jobs after childbirth, supporting better job security for younger people and extending to “support for matchmaking efforts by municipalities and local chambers of commerce.”

More recently, the government has even hinted at encouraging immigration, which is a radical proposal for a nation that has generally not been welcoming of a large influx of foreigners: “In February 2014, the Cabinet Office revealed that Japan will likely only be able to maintain a population of more than 100 million if it accepts 200,000 immigrants annually from 2015 and the total fertility rate recovers to 2.07 by 2030.”

There is much riding on Japan’s effort to halt or at least slow the decline of its population. Other nations, especially across East Asia and Europe, face similar difficulties, so Japan’s success or failure (and the latter seems more likely) could materially impact policies elsewhere in the decades to come.

Note 1: Tokyo prefecture is officially called the Tokyo metropolis, which has led many, including some researchers to imagine it to be the metropolitan area. It is simply a jurisdiction within a metropolitan area more than three times as large.

Note 2: The city of Sapporo is used, because Hokkaido prefecture is far too large to be a metropolitan area (labor market).

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Sapporo (by author)