Perhaps nothing thrills mayors and urban boosters like the notion of endless towers rising above their city centers. And to be sure, new high-rise residential construction has been among the hottest areas for real estate investors, particularly those from abroad, with high-end products accounting for 8o% of all new construction.

Yet this is not an entirely high-end country, and these products, particularly the luxury high-rises in cities, largely depend on a small segment of the population that can afford such digs.

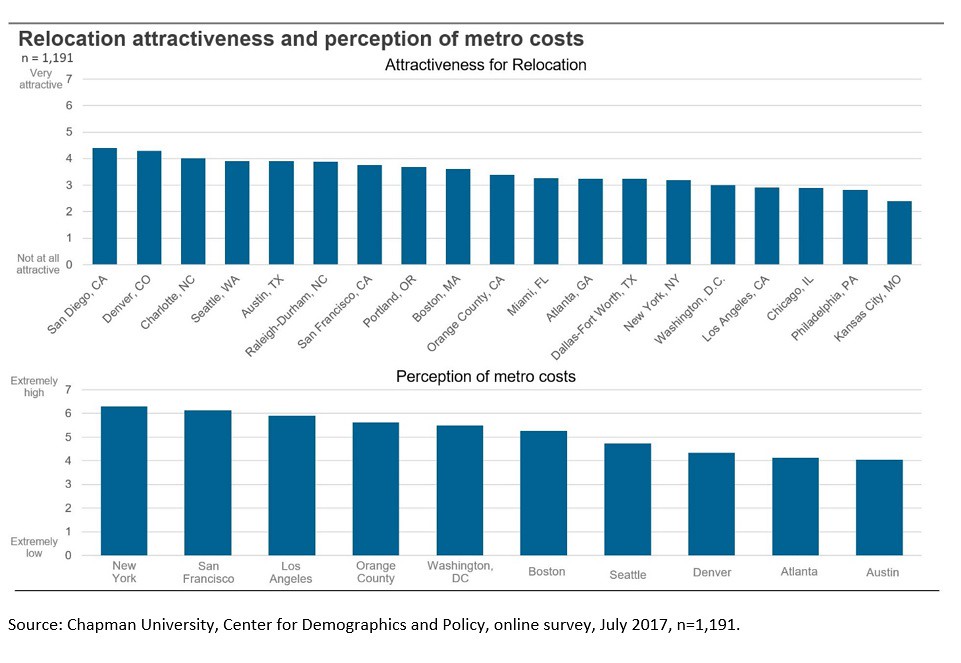

No surprise, then, that we see reports of declining prices in areas as attractive as New York, Miami and San Francisco, where a weakening tech market is beginning to erode prices, much as occurred in the 2000 tech bust, John Burns Real Estate Consulting notes. There have been big jumps in the number of expired and withdrawn condo listings, particularly at the high end; last year, San Francisco saw a 128% spike in the number of withdrawn or expired listings for condos over $1.5 million.

Several factors suggest the high-rise residential boom is over, including a growing recognition that these structures do little to relieve the housing affordability crisis facing middle-class residents, the inevitable aging of millennials and their shift to suburbs and less expensive cities, and the impending withdrawal of some major foreign investors who have come to dominate the market in many cities.

Cost And Affordability

One common refrain among housing advocates and politicians is that high-rise construction is a solution to the problem of housing affordability. The causes of the problem, however, are principally prohibitions on urban fringe development of starter homes. Critics also note that high-rises in urban neighborhoods often replace older buildings, which are generally more affordable.

One big problem: High-density housing is far more expensive to build. Gerard Mildner, the academic director of the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University, notes that development of a building of more than five stories requires rents approximately two and a half times those from the development of garden apartments. Even higher construction costs are reported in the San Francisco Bay Area, where the cost of townhouse development per square foot can double that of detached houses (excluding land costs) and units in high-rise condominium buildings can cost up to seven and a half times as much.

Almost without exception, then, the most expensive areas are precisely those that have the most high-rise buildings: New York, San Francisco, Seattle and Miami. More to the point, these buildings don’t tend to be occupied by middle-class, much less working-class, families. And in many cases, these units are not people’s actual homes; in New York, as many as 60% of new luxury units are not primary residences, leaving many unoccupied at any given time.

Even worse, a high-density strategy tends to raise the price of surrounding real estate. As Tim Redmond, a veteran San Francisco journalist, points out, luxury apartments often tend to be built in areas with older, more affordable buildings. The notion that simply building more of an expensive product helps keep prices down elsewhere misses the distinction between markets; the high-rises in Washington, DC, are not the affordable units that the vast majority of city residents need.

Other cities favored by luxury developers – like Vancouver, Toronto, Seattle and San Francisco – have also seen deteriorating affordability and, in some cases, a mass exodus of middle- and working-class residents, particularly minorities. San Francisco’s black population, for example, is roughly half of what it was in 1970. In the nation’s whitest major city, Portland, African-Americans are being driven out of the urban core by high-density gentrification, partly supported by city funding. Similar phenomena can be seen in Seattle and Boston, where long-existing black communities are gradually disappearing.

The New Demography Works Against This Trend

It is common in retro-urbanist circles to maintain that more Americans, particularly younger ones, will opt to remain customers for ever-greater density, a preference that could sustain an ever-growing market for high-rises. Yet that notion may be past its sell-by date, with demographic evidence suggesting that most Americans, including younger ones, are looking less for an apartment in the sky than for a house with a little backyard.

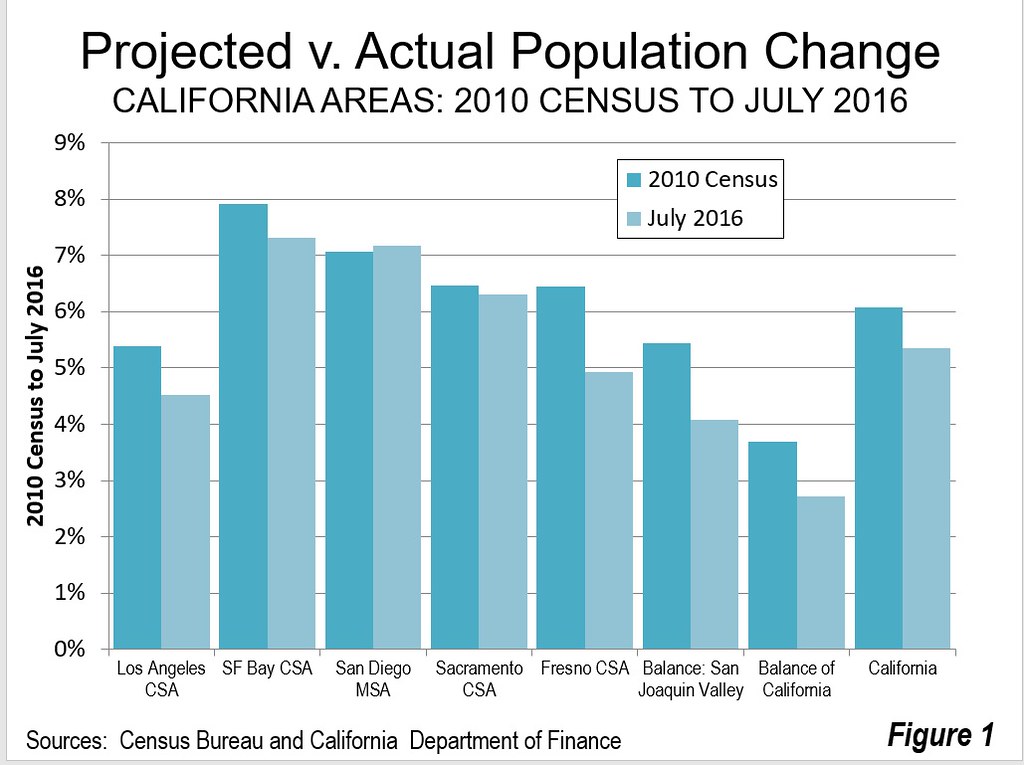

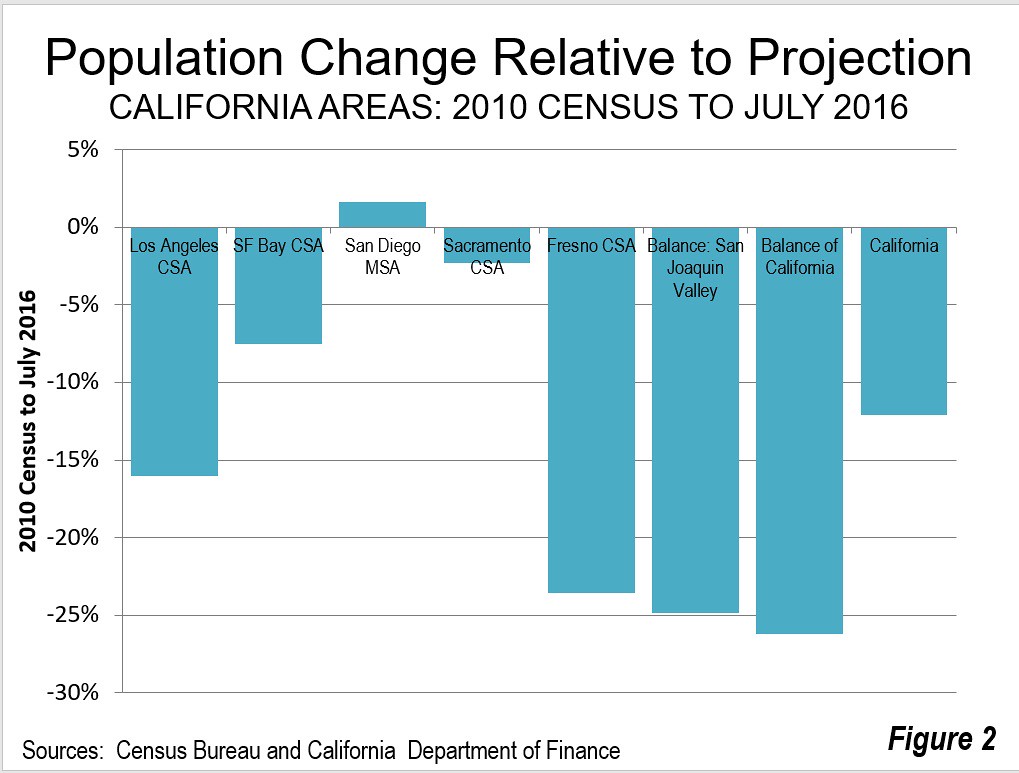

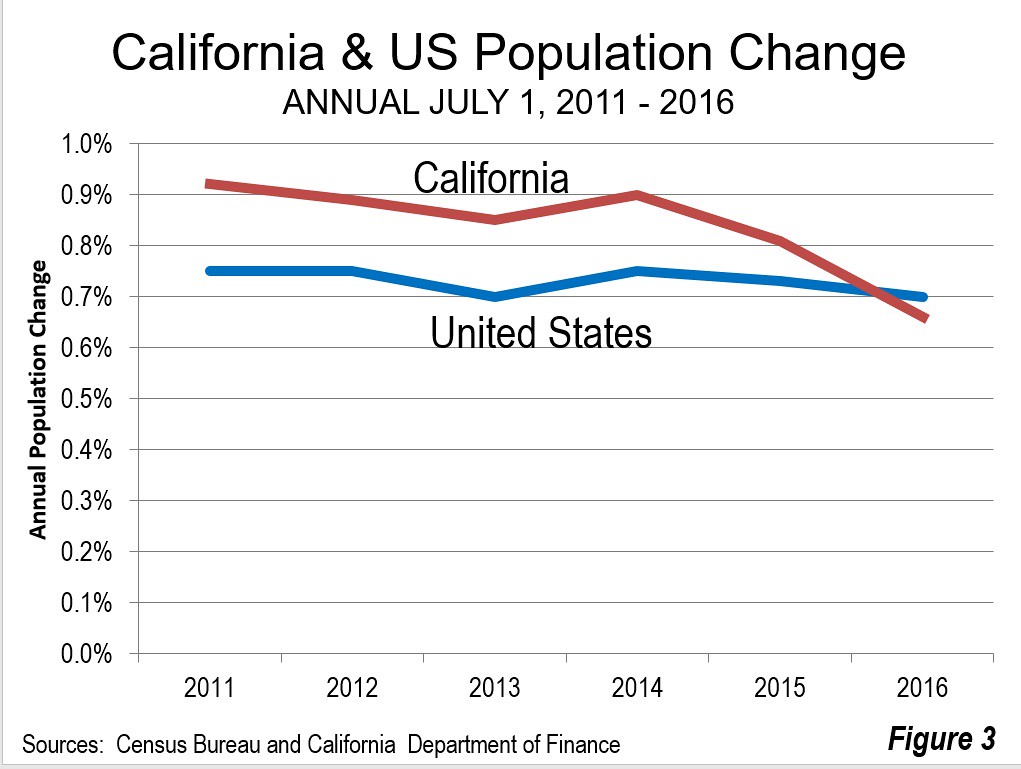

Suburbs, consigned to the dustbin of history by many urban boosters, are back. Demographer Jed Kolko, analyzing the most recent Census Bureau numbers, suggests that population growth in most big cities now lags that of their suburbs, which have accounted for more than 80% of metropolitan growth since 2011. Even where the urban core renaissance has been most prominent, there are ominous signs. The population growth rate for Brooklyn and Manhattan fell nearly 90% from 2010-11 to 2015-16.

The real trend in migration is to sprawling, heavily suburbanized areas, particularly in the Sun Belt. To be sure, there are high-rises in most of these markets – quite a gusher of them in Austin, for instance – but the growth in all these regions is overwhelmingly suburban.

The most critical factor over time may be the aging of millennials. Among those under 35 who do buy homes, four-fifths choose single-family detached houses, a form found most often in suburbs. Surveys consistently find that most millennials see suburbs as the ideal place to live in the long run. According to a recent National Homebuilders Association report, more than 66%, including those living in cities, would actually prefer a house in the suburbs.

The largely anecdotal media accounts of millennial lifestyles conflict with reality, Kolko notes. Although younger millennials have tended toward core cities more than previous generations, the website FiveThirtyEight notes that those ages 30-44 are actually moving to suburban locales more than in the past.

The China Syndrome

Given the limits of the domestic market, the luxury high-rise sector depends heavily on foreign investors.

Already, harder times for some traditional investors – Russians and Brazilians, for example – have hurt the Miami market, long attractive to overseas buyers. There is now three years’ worth of inventory of luxury high-rises there, with areas such as Edgewater, Midtown and the A&E District suffering an incredibly high inventory of seven and a half years. Miami Beach is faring a bit better but is still a buyer’s market at a little over two years of inventory.

Still, the greatest threat to the luxury high-rise market may come from the Far East, the region of the world with the most surplus capital and, given the rapidly aging society, often the fewest profitable places to put it. Korea and Japan have lots of money sitting around looking for a home. Japan and its companies, according to World Bank data, are hoarding more than $2 trillion in unused liquid assets.

But as in all things East Asian, China stands apart. Last year, the country had a record $725 billion in capital outflows, according to the Institute of International Finance. China is now the largest foreign investor in US real estate.

But now the Chinese government has placed strong controls on these investments, which could leave some places vulnerable. In Downtown Los Angeles, according to local brokers, many of the new high-rise towers are marketed primarily in China. (LA claims to have the second-highest number of cranes, behind only Seattle.)

These expensive units are far out of reach for the younger people who tend to inhabit the neighborhood, instead serving as what one executive called “vertical safe deposit boxes” for people trying to get their money out of China. If the new crackdown on such investments is strongly enforced, this could leave a lot of expensive units without buyers. Prices have already softened, and with several new luxury buildings coming up, Downtown is likely to experience a glut.

Even in Manhattan, another market long dependent on foreign investment, projects are now stalled, including some once-hot properties in Midtown that are delaying their sales launches. Overall sales of condos over $4 million dropped 18% last year from the high levels of the previous three years. The ultra-premium market for condos over $10 million saw a 5% sales decrease in 2016.

Changes Ahead

The current slowdown, and perhaps longer-term stabilization, could lead to lower rates of migration out of the expensive cores.

Yet this trend is not likely to reverse the movement of younger people to less dense areas. Luxury high-rise units were not built for families, and they are often located in areas with poor schools and limited open space. They may simply become high-priced rentals, attractive no doubt to childless professionals but not to middle- and working-class families.

In the end, the real need is not for more luxury towers. What is needed, particularly in America’s cities, from the urban core to the urban fringe, is the kind of housing middle- and working-class families can afford.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book is The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo: Sharon Mollerus, via Flickr, using CC License.