When we speak about the ever-expanding chasm that defines modern American politics, we usually focus on cultural issues such as gay marriage, race, or religion. But as often has been the case throughout our history, the biggest source of division may be largely economic.

Today we see a growing conflict between the economy that produces consumable, tangible goods and another economy, now ascendant, that deals largely in the intangible world of media, software, and entertainment. Like the old divide between the agrarian South and the industrial North before the Civil War, this threatens to become what President Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Seward, defined as an “irrepressible conflict.”

Other major economic divides—between capital and labor, Wall Street versus Main Street—defined politics for much of the 20th century. But today’s tangible-intangible divide is particularly tragic because it undermines America’s peculiar advantage in being a powerhouse in both the material and non-material worlds. No other large country can say that, certainly not China, Japan, or Germany, industrial powerhouses short on resources, while our closest cousins, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, remain, for the most part, dependent on commodity trade.

The China syndrome and the shape of the next slowdown

Over the past decade, the United States has enjoyed two parallel booms that combined to propel the economy out of recession. One was centered in places like Houston, Dallas-Ft. Worth, Oklahoma City, and across much of the Great Plains. These areas were all located in the first states to emerge from the recession, and benefited massively from a gusher in energy jobs due largely to fracking.

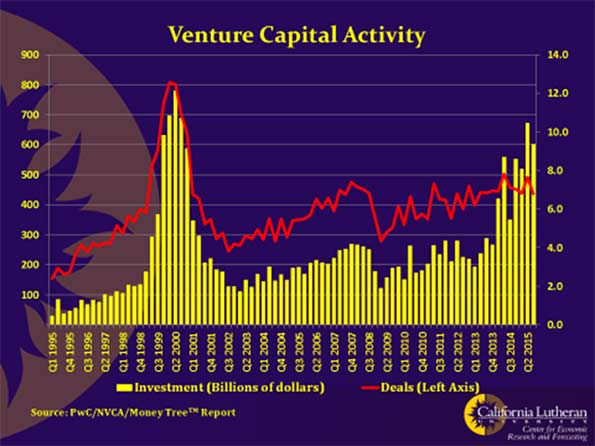

At the same time, another part of the economy, centered in Silicon Valley as well as Seattle, Austin, and Raleigh/Durham, has also been booming. Though far more restricted than their counterparts in the “tangible” economy in terms of both geography and jobs, the tech/digital economy did not lag when it came to minting fortunes. By 2014, the media-tech sector accounted for six of the nation’swealthiest people. Perhaps more important, 12 of the nation’s 17 billionaires under 40 also hail from the tech sector.

Until China’s economy hit a wall this fall, these two sectors were humming along, maybe not enough to restore the economy to its ’90s trim robustly enough to improve conditions in many parts of the country. But as China begins to cut back on commodity purchases, many key raw material prices—copper and iron to oil and gas as well as food stuffs—have fallen precipitously, devastating many developing economies in South America, Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia.

Plunging prices are also beginning to hurt many local economies in the U.S., particularly in the “oil patch” that spreads from west Texas to North Dakota. This is one reason why overall economic growth has fallen, and is unlikely to revive strongly in the months ahead. Overall, according to the most recent numbers, job growth remains slow and long-term unemployment stubbornly high while labor participation is stuck at historically low levels. Much of this loss is felt by the kind of middle and working class people who tend to work in tangible industries.

But it’s not just the much maligned energy economy that is in danger. The recovery of manufacturing was one of the most heartening “feel good” stories of the recession. Every Great Lakes state except Illinois now enjoys an unemployment rate below the national average, and several, led by the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Iowa, boast unemployment that is among the lowest in the nation. Now a combination of a too-strong dollar, declining demand for heavy equipment, and falling food prices threaten economies throughout the Great Lakes and the Great Plains.

Waging war on the tangible economy

President Obama’s emphasis on battling climate change—aimed largely at the energy and manufacturing sectors—in his last year in office will only exacerbate these conflicts. For one thing, the administration’s directive to all but ban coal could prove problematic for many Midwest states, including several—Iowa, Kansas, Ohio, Illinois, Minnesota, and Indiana—that rely the most on coal for electricity. Not surprisingly, much of the opposition to the Environmental Protection Agency’s decrees come from heartland states such as Oklahoma, Indiana, and Michigan. The President’s belated rejection of the Keystone Pipeline is also intensely unpopular, including among traditionally Democratic-leaning construction unions.

These policies have also succeeded to pushing the energy industry, in particular, to the right. In 1990 energy firms contributed almost as much to Democrats as to Republicans; last year they gave more than three times as much to the GOP.

In contrast, the tech oligarchs and their media allies largely embrace the campaign against fossil fuels. Environmental icon Bill McKibben, for example, has won strong backing in Silicon Valley for his drive to marginalize oil much like the tobacco industry was ostracized earlier. Meanwhile the onetime pragmatic interest in natural gas as a cleaner replacement for coal is fading, as the green lobby demands not just the reduction of fossil fuel but its rapid extermination.

Embracing the green agenda costs Silicon Valley little. High electricity prices may take away blue collar jobs, but they don’t bother the affluent, well-educated, Telsa-driving denizens of the Bay Area, who also pay less for power. But those rates are devastating to the less glamorous people who live in California interior. As one recent study found, the average summer electrical bill in rich, liberal andtemperate Marin County was $250 a month, while in impoverished , hotter Madera, the average bill was twice as high.

Many Silicon Valley and Wall Street supporters also see business opportunities in the assault on fossil fuels. Cash-rich firms like Google and Apple, along with many high-tech financiers and venture capitalist, have invested in subsidized green energy firms. Some of these tech oligarchs, like Elon Musk, exist largely as creatures of subsidies. Neither SolarCity nor Tesla would be so attractive—might not even exist—without generous handouts.

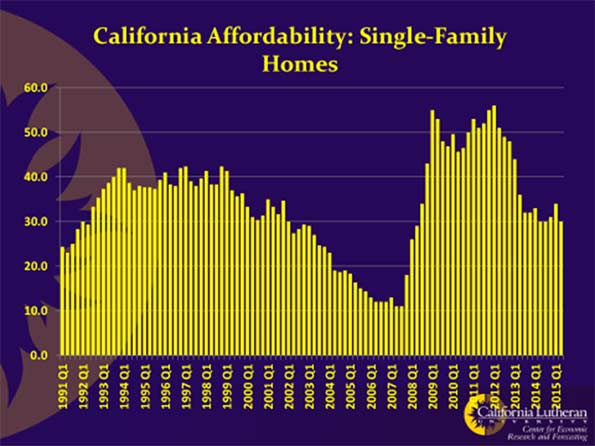

In this way California already shows us something of what an economy dominated by the intangible sectors might look like. Driven by the “brains” of the tech culture, the ingenuity of the “creative class,” and, most of all, by piles of cash from Wall Street, hedge funds, and venture capitalists, the tech oligarchs have shaped a new kind of post-industrial political economy.

It is really now a state of two realities, one the glamorous software and media-based economy concentrated in certain coastal areas, surrounded by a rotting, and increasingly impoverished, interior. Far from the glamour zones of San Francisco, the detritus of the fading tangible economy is shockingly evident. Overall nearly a quarter of Californians live in poverty, the highest percentage of any state. According to a recent United Way study, almost one in three Californians is barely able to pay his or her bills.

Silicon Valley’s political agenda

For the time being, with the rest of the economy limping along, the tech oligarchs seem, if anything, ever more arrogant and sure that they will define the future of the country’s politics. At a time when most small business owners hold Obama in low regard, the Democratic Party can consider the tech sector as an intrinsic part of its core political coalition. In 2000 the communications and electronics sectorwas basically even in its donations; by 2012 it was better than two to one democratic.

Once largely apolitical or non-partisan in their approach, firms like Microsoft, Apple and Google now overwhelmingly lean to the Democrats. President Obama has even enlisted several tech giants—including venture capitalist John Doerr, Linked In billionaire Reid Hoffman, and Sun cofounder Vinod Khosla—to help plan his no doubt lavish and highly political retirement.

The love-fest between Obama and Silicon Valley grows from a common belief in being extraordinary. The same media that has marveled at Obama’s celebrated brilliance also hails Silicon Valley’s ascendency as a triumph of brains over brawn.

Yet in reality many traditional industries such as energy and manufacturing still depend on skilled engineers. Indeed, after Silicon Valley, the biggest concentration of engineers per capita (PDF) can be found in brawny metros like Houston and Detroit. New York and Los Angeles, which like to parade as tech hotbeds, rank far behind.

In contrast to engineers laboring in Houston or Detroit, those who work in Silicon Valley focus largely on the intangible economy based on media and software. The denizens of the various social media, and big data firms have little appreciation of the difficulties faced by those who build their products, create their energy, and grow their food. Unlike the factory or port economies of the past, those with jobs in the new “creative” economy also have little meaningful interaction with working class labor, even as they finance politicians who claim to speak for those blue collar voters.

This may explain the extraordinary gap between the economies—and the expectations—of coastal and interior California. The higher energy prices and often draconian regulations that prevented California from participating in the industrial renaissance are hardly issues to companies that keep their servers in cheap energy areas of the Southwest or Pacific Northwest and (think Apple) manufacture most if not all of their products in Asia.

In the process the Democrats, once closely allied with industry, are morphing into a post-industrial party. Manufacturing in strongholds like Los Angeles, long the industrial center of the country, continues to erode. In a slide that started with the end of the Cold War, Southern California’s once-diverse industrial base has eroded rapidly, from 900,000 jobs just a decade ago to 364,000 today. New York City, which in 1950 boasted 1 million manufacturing jobs, now has fewer than 100,000. Overall, manufacturing accounts for barely 5 percent of state domestic product in New York and 8 percent in California, compared to 30 percent in Indiana and 19 percent in Michigan.

This divide could become decisive in the election. In contrast to advances in energy, autos, and homebuilding, which produced good blue collar and middle-skilled jobs, the benefits of the current tech boom have been limited, both in terms of job creation (outside of the Bay Area) and increased productivity, for the vast majority of voters.

This underlying economic conflict is redefining our politics less along lines of ideology and more in terms of interests. Increasingly states that follow the Obama line on energy, such as New York and California, are not contestable for Republicans. But elsewhere—beyond the coasts—there may be greater resistance.

Among those who are likely to revolt are those workers and entrepreneurs in the oil patch, those who build heavy machinery, and those who grow large quantities of food. The recent Republican win in Kentucky was in part based on opposition to anti-coal regulations coming from the Obama administration. As the EPA ramps up its regulatory onslaught, one can expect energy-dependent industries and regions to recoil, particularly at a time when their industries are headed into a recession. Republicans claims that regulatory policies hurt the tangible economies will gain traction if car factories and steel mills start shutting down again, while farmers plant fewer soybeans and developers build fewer suburban homes.

The emergence of an economic civil war?

Hillary Clinton may praise the economic progress under President Obama, and win the nods of those in the tech, media, and financial community who have done very well on his watch. There’s enough momentum from these industries to guarantee that the entire West Coast and the Northeast will fold comfortably, and predictably, into the Clinton column, despite rising concern about crime, homelessness, and loss of middle class jobs. But the very same policies that attract the tech world voter to Clinton will just as certainly alienate many working class and middle class Democrats in places like Appalachia, the Gulf Coast, and particularly the politically pivotal Great Lakes.

The stakes could be huge. If the Republicans can convince most voters in the middle of the country that the coastal-driven policy agenda is a direct threat to their interests, the GOP will likely carry the day. But if the Democrats can convince the country that coastal California and New York City represent the best future for us all, then get ready for Hillary, because nothing else—certainly not the old social issues—will stop her.

This piece first appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.