Whatever you think of President Trump, his claims about the lousy condition of America’s basic infrastructure are widely accepted—even by resisting Democrats grinding their teeth on a L.A. freeway or waiting for a New York or D.C. train to arrive. His call for a trillion-dollar infrastructure plan may be his last best bet for finding bipartisan support.

The question is if he’s at all serious about the urgent need to fix the failing mass-transit systems we have, or if he’ll repeat what Washington’s done to get us in this mess, and offer funds that encourage cities to build shiny new systems few will actually ride even as the existing ones decay.

As we’ve demonstrated in a new paper for Chapman University (PDF), nowhere is the infrastructure deficit more obvious than in urban transit, which last year lost over 3.1 percent of its ridership, according to the American Public Transit Association (PDF). Despite the vast sums spent by the federal government on light rail, subways, and trolleys since 1970, most mass transit systems fail to meet the needs of commuters.

In many cases, as in New York and Washington, vast expenditures on new lines have occurred even as maintenance has been deferred, with overall service deteriorating. Many billions of dollars more have been spent in other cities on new rail systems that haven’t reduced the number of people driving to work.

How the Feds Failed Legacy Cities

Rail transit works best in what might be considered the “legacy cores.” Approximately 55 percent of America’s transit commuters have destinations in the urban cores (and many of those rides to the central business districts) of six older cities (not metropolitan areas)—New York, Washington, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and San Francisco. New York, by itself, has a remarkable 56 percent of its jobs in its urban core.

Between 2006 and 2015, those six metropolitan areas captured 77 percent of the national increase in transit work trip destinations.

These cities were shaped when public transit held a virtual monopoly on both motorized and horse-drawn passenger transport within U.S. cities. Annual transit ridership peaked in the early 1920s, except for the period around the Second World War, the high-water mark for transit nationally. Between 1960 and 2015, transit’s work trip market share dropped more than 50 percent, from 12.1 percent to 5.2 percent. Until very recently, the demographic recovery of legacy cores, notably New York, drove a slight increase in transit share. But this progress is threatened by growing safety and reliability issues. Part of the problem stems from a decision by New York’s political elite, starting with Michael Bloomberg, to build a new, ultra-expensive line—the Second Avenue subway—while maintenance on other lines deteriorated. This decision reflects political realities including federal incentives for new systems, and the greater political rewards for building shiny new things.

The result is that service delays in New York have skyrocketed as antiquated signals break down, with breakdowns now twice as frequently as they were just five years ago. After decades of increases, ridership has declined while the extensive commuter rail system serving Manhattan from the suburbs (the nation’s largest) is experiencing its own substantial difficulties.

The picture is similar in Washington, D.C., where the U.S. secretary of Transportation went so far as to threaten a shutdown of the system due to fatal accidents, attributed to policies that prioritized system expansion over safety. D.C.’s transit ridership, growing for decades, has now declined as well.

The Real Train Robbery

Yet even as cities that depend on transit, such as New York, suffer from under-investment, Washington has poured billions into new rail system in cities created largely in the auto-dominated era. Among 19 metropolitan areas that have opened substantially new urban rail systems since 1980, the share of riders using mass transit remains below the national average while the share of those driving alone has increased.

Nowhere is the power of ideology and entrenched interests over the common good more evident than in Los Angeles, the pioneer for the multi-polar and highly dispersed post-1950 metropolis.

On the surface, L.A. provides the sunbelt’s best case for transit—it once had a robust transit system, is the densest urban area in the country, has a huge poverty population and ideal weather for waiting outside for the train. L.A. has been widely celebrated as “the next great transit city,” and The New York Times and others are continually celebrating its imminent conversion from a car culture to a train one. Some believers, like Los Angeles architectural critic Christopher Hawthorne, envision “a third Los Angeles” that will see the eclipse of the freeways, single family homes, and suburban neighborhoods.

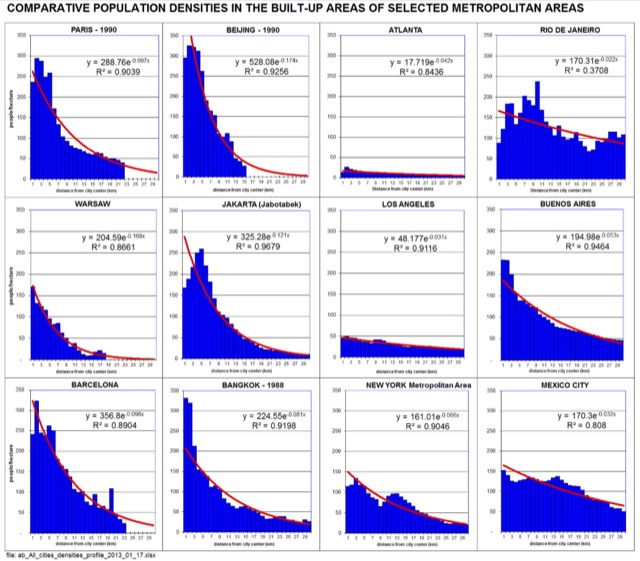

Yet despite this Manhattan envy among its elites, L.A. simply does not follow the “model” of urbanist paragons such as New York, Chicago or San Francisco. Downtown Los Angeles is a relative economic pygmy, accounting for barely 2 percent of regional employment, less than a tenth of lower Manhattan’s share. Transit works best when most commuters are headed to a dominant core destination. The more scattered the destinations, the less likely trains can muster a decent commuter share. The entire Los Angeles MTA system carries fewer riders than New York’s Lexington Avenue line.

Money is not the issue. Since 1990, Los Angeles has opened seven new urban metro and light-rail lines and two exclusive busways at a cost of more than $15 billion. During this period, transit’s work trip market share has dropped from 5.6 percent from 5.1 percent in 2015. Ridership is at least 15 percent below 1985 levels, when there was only bus service and when Los Angeles County had about 20 percent fewer people. No surprise, then, that according to a recent USC study, the new lines have done little or nothing to lessen the area’s infamous congestion.

Rather than hop on the rails, more residents are addressing traffic woes by simply staying home. By 2015, more Los Angeles-area residents were working at home than were taking transit. Since 1990, the number of people working at home increased eight times as rapidly as the number of people using the transit system. The number of people driving increased even more rapidly.

This story is repeated in other sunbelt cities. In Houston, 3.2 of residents commuted to work in 2000, before the city’s $1.5 billion new light-rail system opened. In 2015, the share of commuters had dropped by a third, to 2.2 percent.

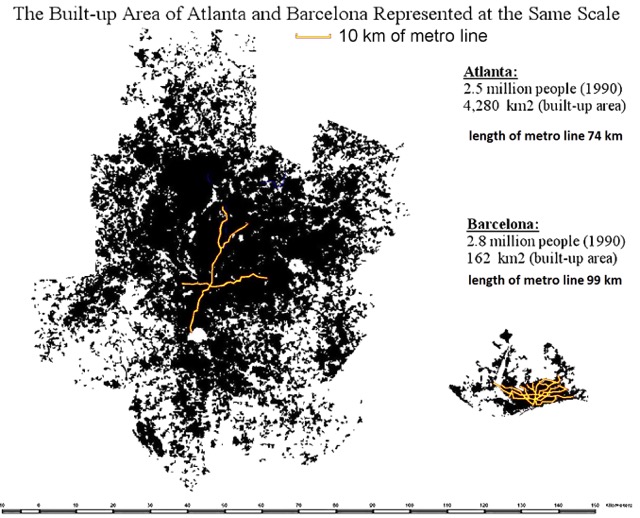

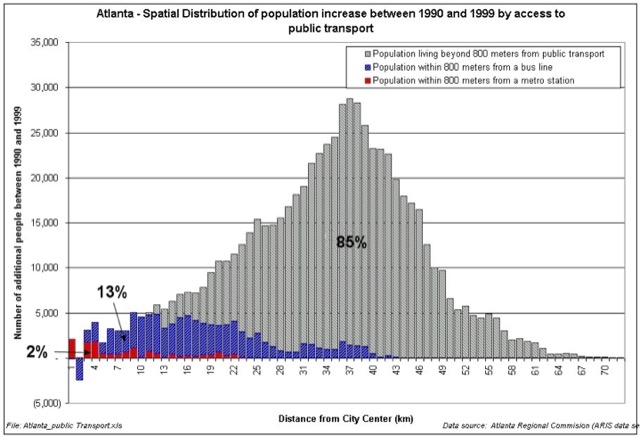

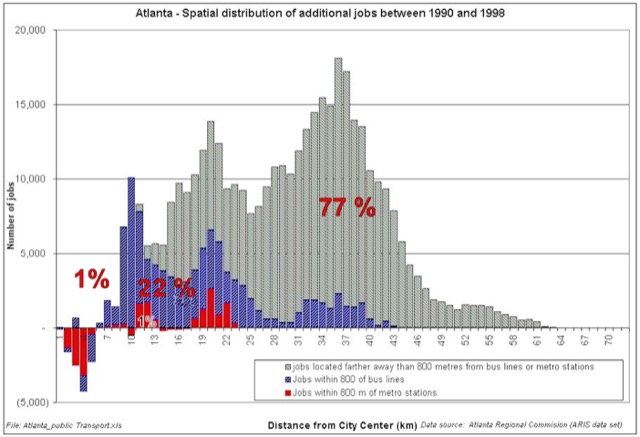

It’s Atlanta, though, that most fully epitomizes the futility of conventional transit spending. With the opening of MARTA in 1979, Atlanta built the third largest new metro system (fully grade separated rail) in the U.S. Since then, transit share has plummeted—from 6.8 percent in 1980 to 3.1 percent in 2015, 40 percent below the average national transit market share. Traffic congestion more than doubled over the same time span.

The most recent addition to Atlanta’s rail system is a central city streetcar line some locals have nicknamed it “a streetcar named undesirable” for its low ridership.

Even urban planning model Portland, which opened its MAX light rail system in 1986, has seen its transit market share drop from 7.9 percent in 1980 to 6.9 percent in 2015, only modestly above the national transit-riding average. The percentage of people working at home rose from 2.3 to 6.4 percent, at virtually no cost to the public treasury, compared to the more than $3 billion to build urban rail.

But the award for the country’s most absurd project should go to the Honolulu elevated rail line. In a metropolitan area of barely a million people, the attempt to build a 20-mile elevated train has increased in cost from $5 billion to an estimated $10 to $13 billion, with the feds chipping in $1.6 billion. The impact on state finances—for an estimated 1 percent drop in road traffic—so disturbed former Governor Ben Cayetano, a Democrat, that he’s publicly called on President Trump to cut future funding. The Honolulu Star-Advertiser recently referred to the elevated lines as an “epic fail on rail.”

The Future of Transit

Before President Trump or Congress tackle infrastructure, they should work to remove federal involvement in control of local transit spending. Some experts like David Levinson of the University of Minnesota, blame federal policy for distorting investment to new project that favor “ribbon-cuttings for politicians” while resulting in neglect for local operations.

In most of the country, simply put, localities would be better off not investing in new rail schemes. Americans seem generally happy with their overwhelmingly suburban lifestyle and their ability to reach places of employment faster than most of those in the high-income world can. Today, over 75 percent of jobs are in the suburbs and exurbs combined. Between 2010 and 2015, 81 percent of job growth was in the suburbs and exurbs. Similarly 85 percent of major metropolitan area residents live outside the urban core, in the suburbs and exurbs, where transit service is sparse.

This is not likely to change much in the near or even medium term. Rather than centralizing, the consulting firm Bain envisions evolution toward a “post-urban economy” that will be more localized and home-based. By 2025, it reports, more people could live “beyond the traditional commuting belt” than inside.

These realities suggest that rather than the “one size fits all” model, metropolitan areas should better customize their transportation spending to local needs. To achieve this, we need to jettison the quasi-religious affection for rail transit and explore in most of the country technologically enabled solutions such as telework, which is growing faster than any form of commuting, as well as rideshare technology. This is particularly true in suburbs, such as Dublin, California, which eliminated their local bus system in exchange for providing vouchers for Uber-like services for those unable to afford or drive cars.

Over the longer term, the autonomous car could make even more revolutionary impacts on both the urban form and transit. Automated car proponents claim that the cost of operations will be considerably below that of today’s cars. If that should be achieved, the autonomous car could be used to provide door-to-door mobility not only for the elderly and disabled, but also for people who currently cannot afford their own cars. Under any circumstances, this innovation seems certain to further weaken conventional transit outside the cities with legacy cores.

Ultimately it will take common sense, even more than just money, to fix our transit problems. In dispersed places like southern California, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Houston, the emphasis may be on using new technologies as well as private express bus service to connect their widely dispersed communities. Monies that go into rail transit, suggest urban analyst Aaron Renn, should be focused on maintaining and improving current service in cities where they make sense. As Renn puts it succinctly: “The priority should be: repairs to existing mission critical rail lines, and helping distressed communities.”

The current trend of wasting billions of dollars to serve a urban theology may be popular among planners, speculators and engineering firms. It hasn’t been particularly helpful to the people who need to get, in appropriate time and without too much stress, from one place to another.

This piece originally appeared on the Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book is The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo by Gage Skidmore, via Flickr, using CC License.