Once a fringe idea, the notion of using technology to allow humanity to “decouple” from nature is winning new attention, as a central element of what the Breakthrough Institute calls “ecomodernism.” The origins of the decoupling idea can be found in 20th century science fiction visions of domed or underground, climate-controlled, recycling-based cities separated by forests or deserts. A version of decoupling was promoted in the 1960s and 1970s by the British science writer Nigel Calder in The Environment Game (1967) and the radical ecologist Paul Shepard in The Tender Carnivore and the Sacred Game (1973). More recent champions of decoupling include Martin Lewis, Jesse Ausubel, Stewart Brand, and Linus Blomqvist.

Proponents of decoupling point out correctly that the greatest threat to wilderness is not urban sprawl, but agricultural sprawl. The amount of the earth’s surface devoted to the unnatural, simplified ecosystems of agriculture—that is, farms and ranches—dwarfs the small amount consumed by cities, including low-density suburbs. Industrial, energy- and fertilizer-intensive agriculture has permitted us to grow far more food on far less land—with costs, to be sure, including water pollution from fertilizer runoff. Genetically modified crops will make it possible to shrink the footprint of global agriculture altogether, and if human beings ever derive most of their diet from laboratory-synthesized foods like in vitro meat and vegetables created from stem cells, most of today’s farmland can be freed for other uses.

The decouplers are right to predict that technology will free up vast amounts of land for purposes other than farming. But many of them go wrong, I believe, when they assume that the decline of agricultural sprawl will be accompanied by the decline of urban sprawl, for two reasons. First, as societies become richer, more and more people choose low-density housing and can afford it. Second, whatever may be the case in other countries, in the United States, the private market for land—including retired farmland—ensures that little if any of the land freed by technology from agriculture will be turned into public wilderness preserves.

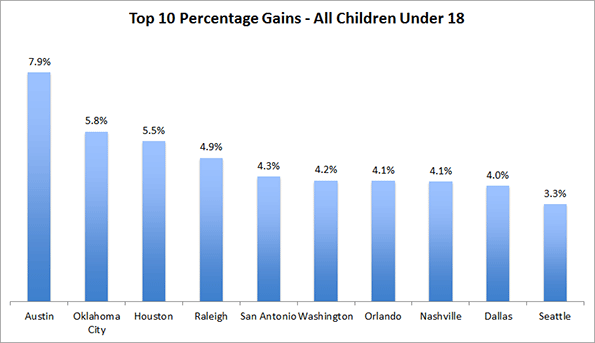

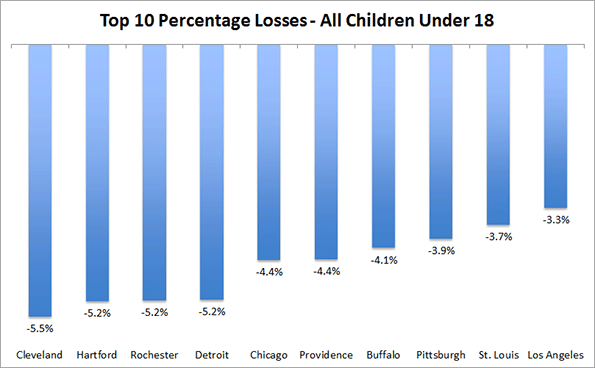

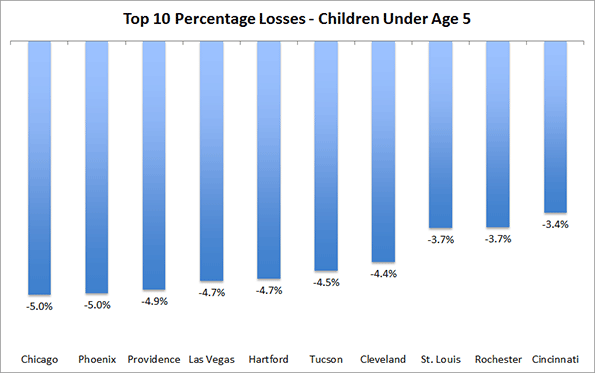

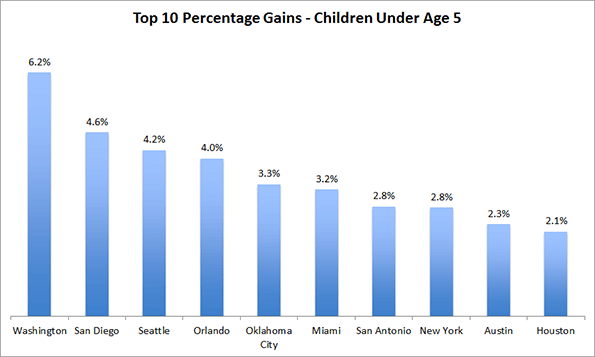

One of the great urban legends of our time is the claim, endlessly repeated by urban gentry journalists, that Americans are tired of the suburbs and are moving back into the city in the search of walkable neighborhoods. The data disprove the claim. As Wendell Cox points out at Newgeography:

But the core municipalities now contain such a small share of major metropolitan area population that the suburbs have continued to add population at about three times the numbers of the core municipalities…Indeed, if the respective 2010-2013 annual growth rates were to prevail for the next century, the core municipalities would house only 28.0 percent of the major metropolitan area population in 2113 (up from 26.4 percent in 2013).

Thanks to decoupling, the low-density metro areas will probably become even bigger and even less dense. As farmland on the periphery of metro areas is retired from agriculture, much of it will be converted into cheap housing, low-rent office parks and inexpensive production facilities.

The rise of robocars may accelerate metro area decentralization. Congestion will be reduced, and the greater safety of driverless cars may permit higher speeds on metro area beltways and cross-town freeways. Once taxi drivers are replaced by robot taxis, the cost of taxis will plummet and the greater convenience of point-to-point personal travel anywhere in a sprawling metro area will make rail-based mass transit obsolete except in places like airports and tourist-haven downtowns. As in the past, most working-class families with children will probably prefer a combination of a longer commute with a bigger single-family house and yard to a shorter commute and life in a cramped apartment or condo.

Nor will most working-class and middle-class retirees move to walkable downtowns. They won’t be able to afford to. And robocars plus in-home medical technology will make it much easier for the elderly to age in place in car-based suburbs.

As great numbers of middle- and low-income Americans move to bigger, cheaper homes on the former farmland that rings expanding metro areas, they will be leap-frogged by the rich. Absent a reversal of today’s top-heavy income concentration, much of America’s wealth will continue to be concentrated in the hands of a few people. And when farmland is retired, thanks to GM crops, in vitro food, or other new land-sparing technologies, a lot of the former farm acreage will be bought by One Percenters and turned into rural retreats.

The decouplers hope that retired farmland will be “rewilded” and transformed into nature parks that everyone can enjoy. But how realistic is this hope? At least in the United States, it is impossible to imagine federal or state governments buying more than a negligible portion of retired farmland and turning it into public parks. What is more likely, that most retired Midwestern farmland will be turned into rewilded public prairie preserves—or that it will be divided into the vast baronial estates of super-rich bankers, tech oligarchs, and trust-fund heirs and heiresses, who commute from their downtown skyscraper penthouses to their high-tech Downtown Abbeys?

A certain amount of the former farm acreage owned by the plutocracy may be rewilded, with the encouragement of tax incentives like conservation easement laws. But rewilding on the scale imagined by some environmentalists is unlikely. For one thing, the former farmland will still be chopped up by fences, roads, power lines, and other structures. And all but the greatest recreational ranches will be too small to support self-sustaining populations of bison and other megafauna. Nor are voters likely to smile on the restoration of predators like wolves, coyotes, bears, and mountain lions, even if a few of eccentric rich landowners fancied the idea.

And then there is the aesthetic factor. The biologist E.O. Wilson has suggested that, because we are descended from hominids who evolved on African savannahs, we naturally prefer vistas with grassy expanses to forests, deserts, and other biomes. Some evidence for this comes from the work of the Russian artists Komar and Melamid, who polled members of different nationalities and then painted the “Most Wanted Paintings” based on the results. In most countries, if they are to be believed, the favorite sofa painting shows a grassy landscape with a river and some woods in the background.

As Paul Shepard pointed out, the country-house landscape of 18th century Britain was anything but natural. The natural landscape of most of Britain, as of most of Western Europe, is dense forest. But the British rural upper class cleared the forests to create grassy vistas—the ancestors of the modern British and American suburban lawn. Shepard blamed this on the influence of Renaissance Italian landscape painting, which showed once-forested Mediterranean coast land that had been denuded by goats and sheep. But the Wilson theory may provide another explanation.

Whether for cultural or instinctive reasons, the rich who buy up most of the land spared by technology may wish to keep open spaces, even if the area would naturally be forest. The late architect Philip Johnson waged a constant war on the New England forest in order to maintain grassy lawns over which to view his Glass House and other iconic buildings on his 47-acre New Canaan, Connecticut, estate. In prairie biomes, conversely, the rural rich are likely to plant some trees, to make the land conform to conventional notions of the scenic.

If the American rich are given a free hand to shape the former farm acreage they have bought, the most likely result will be a park-like landscape, with open vistas and clumps of trees—regardless of what the natural environment of the area would look like. The rewilding would be limited chiefly to small animals and birds, like raccoons and turkeys. No bison herds and no wolf packs. And as acreage was converted from farmland to One Percenter parkland, the already excessive deer population, freed from natural predators and rural American hunters alike, would swell even more.

The decouplers are right, I believe, to predict that advances in food production technology will free enormous amounts of former farmland for other uses. But very little of that land will be converted into the public wilderness preserves envisioned by Calder and Shepard and others. A minority of the former farmland will be converted into single-family housing on the edges of major metro areas. Most of the land retired from farming, instead of being spared for nature, will become rural estates for the plutocracy, surrounded by signs reading PRIVATE PROPERTY: KEEP OUT and overrun by starving deer.

Michael Lind is the Policy Director of the Economic Growth Program at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C., editor of New American Contract and its blogValue Added, and a columnist forSalon magazine. He is also the author of Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United States. Lind was a guest lecturer at Harvard Law School and has taught at Johns Hopkins and Virginia Tech. He has been an editor or staff writer at the New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, the New Republic and the National Interest.