The election of Barack Obama promised to inaugurate the dawn of a post-racial America. Instead we seem to be stepping ever deeper into a racial quagmire. The past two month saw the violent commemoration of the Ferguson protests, “the celebration” of the 50th anniversary of the Watts riots, new police shootings in places as distant as Cincinnati and Fort Worth, and renewed disorder, tied to a police-related shooting, in St. Louis last week.

When President Obama was elected, two-thirds of Americans thought race relations were good. Now six in 10 think they are bad, according to a New York Times poll, including some 68 percent of African Americans.

This extreme alienation creates a rich soil for resurgence of a cramped form of black nationalism, as revealed in such widely read books as Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. Coates, like the black nationalists of the ’60s, is fawned over by today’s progressive gentry. New York Times film critic A.O. Scott gushed that Coates’s writing is “essential, like water or air.” Yet the new nationalists do not, like many previous iterations, look to Africa for salvation, and as a potential place of re-settlement. Instead they may look to Africa for inspiration, but seem content to stew in the American racial cauldron, always apart but also here.

Yet to this reader, it’s hard to regard Coates’s book as anything more than a narrow selfie that holds little hope for any future racial progress. To Coates, America itself seems irredeemable, its very essence tied to racial oppression and brutality. America is not about ideals not yet fulfilled, but a legacy of “pillaging,” the “destruction of families,” “the rape of mothers,” and countless other outrages. Today’s abusive police—and clearly some can be so described—are not outliers who should be punished but “are merely men enforcing the whims of our country, correctly interpreting its heritage and legacy.” His alienation from America is so great that he admits to little sympathy for the victims of 9/11.

He has particular contempt for those blacks who seek to succeed within the American system, although Coates, a talented rhetorician, has clearly done well for himself. To him, they are deluded into believing they can make their way by “acting white, of talking white, of being white.” African-American families that have broken away from the inner city or the poor small town and found a home in the suburbs, he suggests, “would rather live white than live free.” In language no doubt reassuring to New York urbanistas, he even accuses these blacks of participating in a grand global destruction merely because they drive cars and live in suburbs.

Coates’s book also reinforces other nationalist voices such as can be found in certain vocal corners of the “Black Lives Matter” movement, which seems to have little room for the inclusive humanism that characterized the early ’60s civil rights campaigners. They shout down genuine progressives like Bernie Sanders and poseurs like Martin O’Malley for insisting that “all lives matter.” In this world-view all police are tarred similarly; in this construct, clear abuses, such as the Eric Garner case, are no different than that of Michael Brown in Ferguson, which even the Obama Justice Department found unworthy of federal prosecution.

The current radicalization of some prominent black thinkers poses some challenges to Democrats in particular, reflecting their increased dependence on lopsided support from African Americans. Republicans may be doomed to become “the white man’s party,” as my old friend Harold Meyerson suggests, but who thinks the GOP’s insularity deserves emulating? Do the new black nationalists think they have anything to sell outside the confines of liberal bastions or inner-city African-American communities?

Ultimately this program represents a dead end, both for the country and its increasingly diverse population. Ta-Nehisi Coates can’t expect to castigate whites as brutes who need to oppress blacks for both self-esteem and economic survival and then expect these same brutes to get on board with concessions, subsidies, and even reparations. Many academics and mainstream journalists may go along with such a program, but this is not a reasonable strategy for the rest of the country.

***

When desegregation began in earnest in the ’60s, the hope was that we would see the emergence of greater equality between minorities and whites. And to be sure, there was reduction in black poverty in the booming ’60s, and then again during the Reagan and Clinton expansions. Yet in ensuing years, and especially with the onset of the Great Recession, this progress reversed, in large part because black and Latino families bore the brunt of the foreclosure crisis. African Americans saw their household wealth plunge 31 percent during the recession, including a steep 35 percent decline in their retirement assets, according to the Urban Institute. By comparison, the wealth of white families fell a relatively mild 11 percent from 2007 to 2010.

This growing disparity has prompted demands for expanded racially-derived benefits that, according to advocates like former Attorney General Eric Holder, should be a permanent part of national policy. “The question,” says Holder, “is not when does it end, but when does it begin … When do people of color truly get the benefits to which they are entitled?”

This idea has been further expanded by the Obama administration’s commitment to correcting what it calls “disparate impact,” which would force communities—presumably middle-class suburbs—to accommodate poor and minority residents at taxpayer expense, if the federal Housing and Urban Development or the courts deem it appropriate.

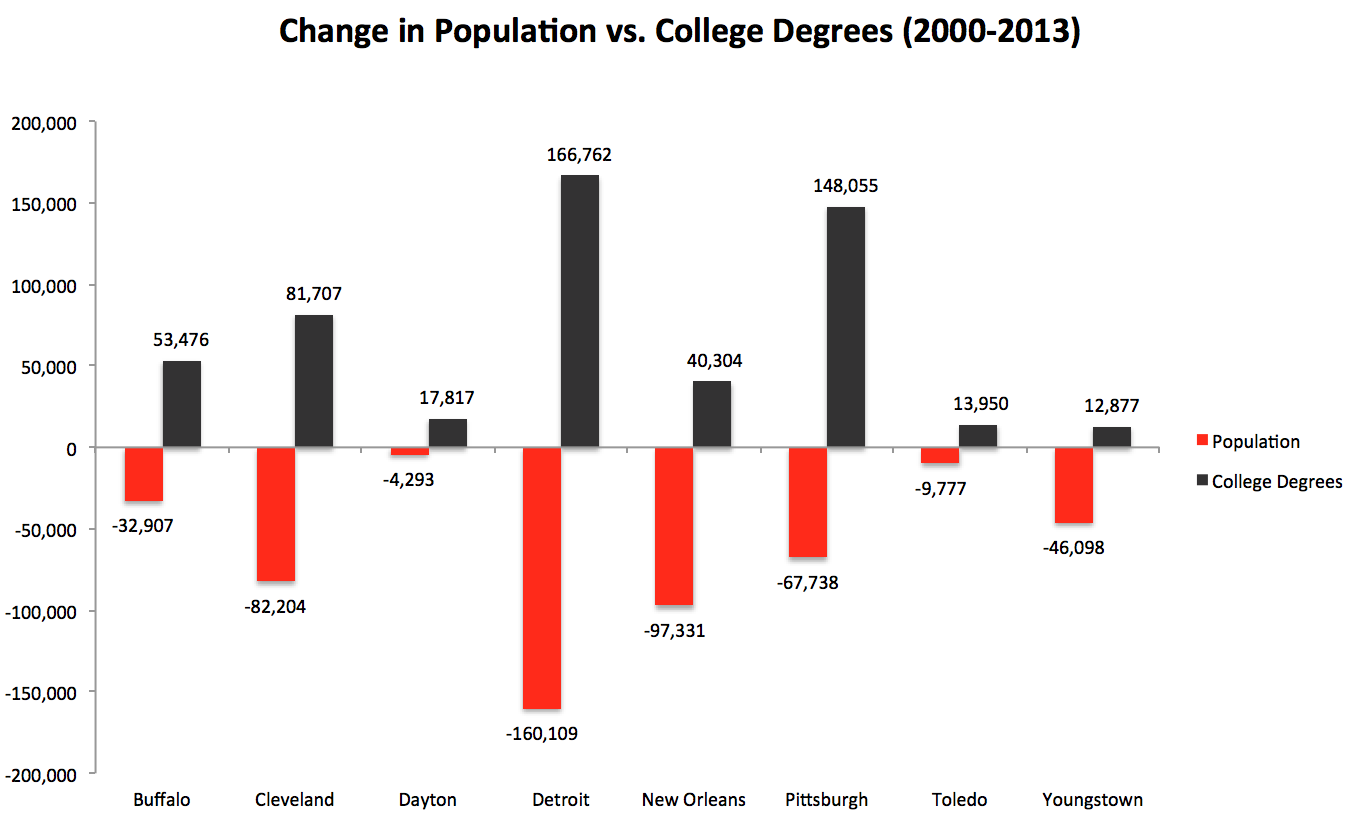

Such an approach negates the aspirations of middle-class families, including many African Americans who have headed to the suburbs for a better life.Upwardly mobile African Americans have been deserting core cities for years: Today, only 16 percent of the Detroit area’s African Americans live within the city limits.

The big problem here is the emphasis on legal remedies and identity politics, rather than focusing on economic empowerment for Americans of all ethnicities. Perhaps as much as any senior government official, Holder argued in support of a quota regime, which at its logical extreme guarantees that even the children of black billionaires get preferences easier than a white kid brought up in an Appalachian hovel.

Yet this is the same official who gently treated Wall Street malefactors—the very people in large part responsible for millions of foreclosures, including those that affected many blacks—to an extent that even the usually pro-Obama Rolling Stone openly wondered if he was a “Wall Street double agent.”

The Obama years—following the previous disasters left over from the Bush regime—have been largely an economic disaster for black America. Child poverty is at the highest level in 20 years, and among African Americans it stands at a disastrous 38 percent, rising even during the recovery. After decades of gradual decline, concentrated urban poverty has grown rapidly over the past decade.

Nor have African Americans benefited much from the recovery. White American unemployment is either about the same or below what it was before the recession levels, while the gap with African Americans has grown, in some states two and a half times that of the majority population. In Washington, D.C., the fundamental center of blue-state America, it’s five times as high.

Far more helpful than expanding racial quotas would have been steps to put African Americans to work, particularly teenagers, who suffer nearly 30 percent unemployment rate, twice the national average. Many African Americans, for example, could have benefited more from a revival of the old Works Progress Administration, which would have put unemployed and underemployed people to work, than from any extension of affirmative action in universities. It’s hard to see how doling out “green” subsidies and breaks to Silicon Valley and Wall Street crony capitalists has been much of a benefit to African-American communities, or other underserved minorities.

Nor is the overall Obama environmental program—particularly on energy—helpful to African-Americans who need jobs in basic industries and in some places, such as California, are stuck with high electricity bills. Harry Alford, head of the U.S. Black Chamber of Commerce, accuses the EPA of “apparent indifference to the plight of low-income and minority households,” which he calls “inexcusable.”

For Coates’s part, he claims several times in his book that America depends on the oppression of blacks—who, he claims, represent “the essential below,” an oppressed class of workers whose sweat and blood propel America’s economy. This may well have been true in the times when cotton was king and the South produced most of our exports. But for many states in 2015, the fact is that the low-wage labor force is now made up of workers largely from Latin America or Asia, who do the grueling work that blacks too often performed in the past.

In a multi-racial society—where African Americans are in many places the second- or third-largest minority—black communities must focus on developing a competitive economic advantage. There are traditions here to draw on, from such disparate figures as Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey, who emphasized the need to be competitive with other peoples. The role models are not posturing Black Panthers but those who built institutions like Tuskegee Institute or even Howard University, Coates’s “Mecca.” Instead, Coates seems to prefer the theatrical racialism of the Panthers, whose legacy of violence left little in terms of tangible accomplishments, but who, like him, can count on the continued fawning approval of white intellectuals.

Revolutionary posturing and racial redress may appeal to New York publishers, but economic success requires more than identity politics. Community members must loan to each other, start banks and nonprofits, and seek to dominate specific niches. In contrast, how much independent wealth or how many jobs have been created by the likes of Al Sharpton, whose career is largely one of extracting money from frightened corporate donors seeking anti-racist absolution?

Ultimately the fate of black America is no different from the fate of the country as a whole: Both depend on economic progress more than political agitation. In a recent study I conducted with colleagues at the Center for Opportunity Urbanism, we found that the cities where African Americans and other minorities did best—measured by employment, income, homeownership—were those that created the most jobs, particularly for mid-skilled workers, and kept costs, particularly for housing, low.

These included primarily regions in the least “progressive” parts of the country, such as the Southeast. Since 2000, when the census registered the first increase in the region’s black population in more than a century, the “Great Migration” to the North has now reversed and is heading back South. In our survey, the South accounted for a remarkable 13 of the top 15 metro areas for African Americans. Blacks in Texas, for example, suffer an unemployment rate 50 percent lower than blacks in California. School segregation, notes the University of California’s Civil Rights Project, is greatest in the Northeast and urban areas and least pronounced in the Southeast and the suburbs.

***

Despite all the negative aspects of America’s tortured racial history, comparing today’s situation to that of the early 20th or even 19th centuries—most particularly in the South—is misleading and hyperbolic. America is no longer a black-white country and many newcomers, such as Asians, also suffered severe discrimination but have made enormous progress. Yet today Asians enjoy higher incomes and levels of education than whites. Increasingly they are no longer the subjects of affirmative action, but among its primary victims.

Perhaps even more revealing has been the progress of African immigrants, who represent one of the fastest-growing parts of our newcomer population. Between 2000 and 2010, their numbers grew from 800,000 to more than 1.6 million, and since 2010 grew by another 100,000, expanding faster as an immigrant group than those from any part of the world. Like African Americans, they are moving increasingly to Southern states, notably Texas and Virginia. As a group, they have done well in terms of income, education, and entrepreneurship.

To be sure, most Africans in America, like Latinos and Asians, do not carry with them the burdens of slavery, or as consistent a long history of legal discrimination. They came here by choice and this no doubt influenced their behavior. Yet the success of other minorities does suggest that lingering racism, so deeply entwined in the analysis of Coates and other neo-black nationalists, does not present an insurmountable barrier.

Of course, there is no clear pattern of such discrimination by police against Asians, and no way to distinguish the experiences of African immigrants from other blacks in terms of crime. Yet each group each is physically distinct, and they have not allowed this fact to prevent their ascendency in American society. This is not to say that serious changes in policing are not necessary—there certainly are—but that the focus of ethnic uplift needs to be focused not on what “they” do to you, but what you can manage to accomplish yourself despite their depredations.

America’s racial divide cannot be bridged anymore by demonizing the country than by ignoring the issue. America is not, and won’t be, entirely “color blind” any time soon. But that is somewhat beside the point—the key to economic success lies not in celebrating or exploiting victimhood but in people moving forward both as individuals and groups.

Simply put, to suggest that America is as racist today as in 1865 or 1965 is absurd, given the reality of the Obama presidency or, more specifically, given the demonstrable change in national attitudes. In 1958, a mere 4 percent of the population endorsed racial intermarriage, while today that percentage has risen to 87 percent. These views are particularly deeply felt among millennials, who are themselves the most diverse generation in American history.

In the long run, demanding an economy with sufficient opportunities represents the best way to address racial disparities. The new black nationalists may be feted by the intellectually chic, but in the end their strategies can only leave their people in a cul-de-sac of disappointment, anger, rage, and, ultimately, impotence.

This piece first appeared in The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo by flickr user amir aziz