I’m regularly accused of being a doomer whenever I point out the obvious – that many aspects of how we’ve organized our affairs over the last several decades aren’t meant to last. So they won’t. The end of Jiffy Lube and Lean Cuisine isn’t The End. Civilization will carry on without them, I assure you. But when it’s suggested that our current set of arrangements won’t last forever people immediately imagine Mad Max, as if no other alternative exists. Things are going to change. They always have and they always will. The future will just be different. That’s absolutely not the same as saying the world is coming to an end. Clear eyed individuals who are paying attention can start to get a feel for who the new winners and losers are likely to be and place themselves in the best possible situation ahead of the curve. That’s a pragmatist’s view – not a doomer’s.

It helps to explore previous versions of these regularly occurring historical shifts. Think of them as postcards from the last few rounds of the Zombie Apocalypse. Here’s a small farm town in rural Nebraska. Its population peaked in the 1920s. The period between World War I and the Great Depression was an especially prosperous time for such towns as commodity prices were high and technological innovation (the telephone, radio, automobiles, tractors, etc.) created an enormous amount of new wealth and opportunity. The 1920s was also an era of rampant unsustainable practices of all kinds that lead to the ruined soils and draughts of the Dustbowl and the collapse of speculative credit based financial institutions. The population of this town began to decline in the 1930s and is currently down to a few dozen souls.

Remnants of some of that early twentieth century technology still litter pastures on the edge of town. One resourceful farmer organized these old car carcasses into a makeshift corral for his livestock.

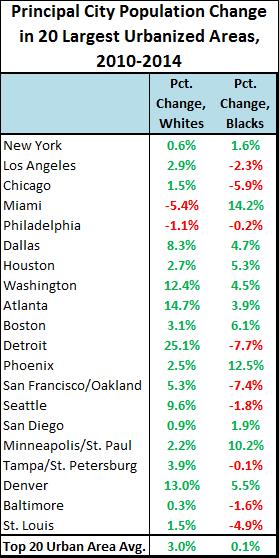

It’s possible to connect the dots from rural Nebraska to Detroit where those very same vintage vehicles were manufactured all those decades ago. Detroit peaked in population, economic power, and political influence in 1950. Today huge swaths of Motown look remarkably similar to the abandoned farms and small towns of the prairie. Entire city blocks are now cleared of people and buildings. The Zombie Apocalypse arrived there too. If small scale agriculture was made redundant by mechanization and industrial scale production, then industry itself was hammered by other equally powerful forces. Everything has a beginning, middle, and end.

The most recent iteration of the Zombie Apocalypse has already begun to unfold in some places. Suburbia was exactly the right thing for a particular period of time. But that era is winding down. The modest tract homes and strip malls built after World War II are not holding up well in an increasing number of marginal landscapes. I have been accused of cherry picking my photo ops, particularly by people who engage in their own cherry picking when discussing the enduring value of prosperous suburbs. But there’s too much decay in far too many places to ignore the larger trend. The best pockets of suburbia will carry on just fine. But the majority of fair-to-middling stuff on the periphery is going down hard.

The desire to push farther out and build ever more upscale suburban developments in increasingly remote locations is palpable. That’s what a significant proportion of the population desires on some level. But in the same spots – often next to each other – is ample evidence that there’s something profoundly wrong.

Not all farm towns died. Not all industrial cities collapsed into ruin. Not all suburbs will fail… But the external forces at work are going to favor some places much more than others moving forward. The trick is to understand what those forces are before everyone else does and position yourself to benefit instead of getting whacked by the shifts. Would you have rather sold your house in Detroit in 1958 when things were still pretty good, or wait until 1967 when the panicked herd began to stampede? Would it have been better to buy property in the desert in 1970 and take advantage of a wave of growth for a few decades, or buy now at the top of that cycle and slide down from here on out?

The future drivers of change will be the same as the previous century – only in reverse. The great industrial cities of the early twentieth century as well as the massive suburban megaplexes that came after them were only possible because of an underlaying high tide of cheap abundant resources, easy financing, complex national infrastructure, and highly organized and cohesive organizational structures. Those are the elements of expansion.

But once the peak has been reached there’s a relentless contraction. The marginal return on investment goes negative as the cost of maintaining all the aging structures and wildly inefficient attenuated systems becomes overwhelming. The places that do best in a prolonged retreat from complexity are the ones with the greatest underlying local resource base and most cohesive social structures relative to their populations. The most complex places with the most critical dependencies will fail first as the tide recedes.

The next Zombie Apocalypse will relentlessly dismantle superficial decorative landscapes and highly leveraged economies of scale. Take away the twelve thousand mile just-in-time supply chains, heavy debt loads, and limitless cheap resources and you get a very different world. Over the long haul Main Street has a pretty good chance of coming back along with the family farm. But the shorter term in-between period of adjustment to contraction is going to be rough as existing institutions attempt to maintain themselves at all costs.

This piece first appeared on Granola Shotgun.

John Sanphillippo lives in San Francisco and blogs about urbanism, adaptation, and resilience at granolashotgun.com. He’s a member of the Congress for New Urbanism, films videos for faircompanies.com, and is a regular contributor to Strongtowns.org. He earns his living by buying, renovating, and renting undervalued properties in places that have good long term prospects. He is a graduate of Rutgers University.