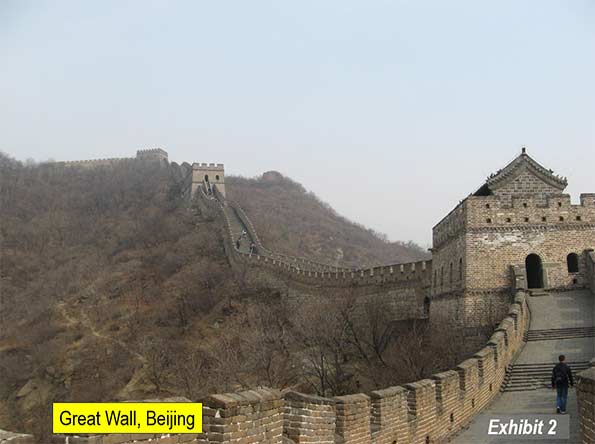

Recently concluded agreements between the United States and China have led to easing of visa restrictions, which is expected to lead to tourist volume increases in both directions. As a frequent traveler to China, I have found that organized groups – the simplest way to travel in China – far too confining and have avoided their use with the exception of travel to a Great Wall site in the Beijing area.

It is easy to obtain a visa by mail or express to visit China by applying through a Chinese consulate or visa service. These are readily found on the internet. It may be surprising that obtaining a visa to visit China is easier than obtaining a visa for a US visit by Chinese citizens, which requires a face-to-face interview with a US consular official.

Purpose of My Travel

My principal professional interest is cities. I have toured all of the urban areas with more than 1,000,000 residents in Western Europe, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States and nearly all of the world’s megacities (over 10 million people). My purpose has been to examine the geography, urban form and transport system of world cities

China has become a particular interest, not only because of its unprecedented economic trajectory and its poverty reduction, but also because of its strong rate of urbanization. According to the United Nations, in 1975, China was 17 percent urban, and will reach 56 percent in 2015, three times the level of 40 years ago. I have traveled extensively in China over the past 15 years and toured each of the 27 largest urban areas and a number of smaller urban areas.

Getting There

Chances are that the individual tourist will enter China through one of its two largest international airports in Beijing and Shanghai.

Beijing’s Capital International Airport was rebuilt for the Olympics and is an architectural masterpiece. Capital International Airport now trails only Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in passenger volume. As late as 2002, Capital International did not rank among the world’s top 25 airports. There is a limited stop Metro line to the core of Beijing, costing about $4.

Shanghai’s Pudong International Airport has been substantially expanded in recent years, and unlike many airports, has maintained a consistent architectural design, despite its additions. Pudong International is unique is being served by the world’s only Magnetic Levitation train ("maglev") which takes passengers part way to central Shanghai, at speeds up to 270 miles per hour (430 kilometers per hour). The Mag Lev is the fastest train in the world in commercial operation. The one-way fare is approximately $8 (Note 1). The core of Shanghai can be reached from Pudong by Metro for slightly more than $1.00 (29 miles or 47 kilometers).

One option the tourist will not find at Chinese airports is the self-drive rental car counter. Generally, rental cars are available only to drivers with a Chinese driving license.

Not Getting Lost

Some in China speak English, but the vast majority do not. As is noted below, the principal means of travel within the cities is by taxi and most taxi drivers do not speak English. Therefore it is very important to always take an "address card," which will have the hotel name and address printed in both Chinese characters and English, so the taxi driver can return you to the hotel. Hotel personnel will also write destinations in Chinese characters to give to taxi drivers for trips from the hotel.

Getting Around in Urban Areas

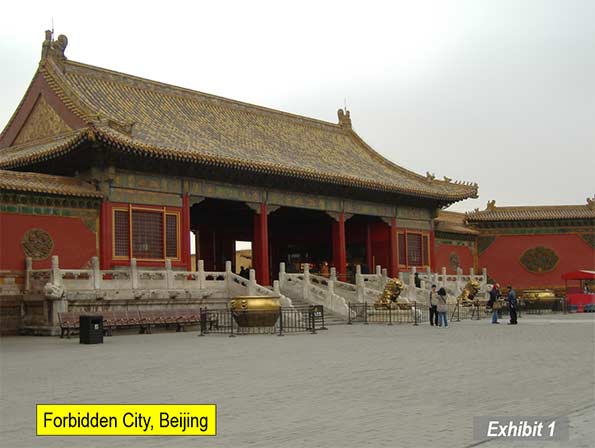

Even so, the urban transportation system meets the needs of most tourists. China’s cities are by no means walkable, though some attractions will be available on foot. For example, many central Beijing hotels are within walking distance of Forbidden City. In Shanghai, the Bund and the Nanjing Road shopping district (Note 2) are also near central area hotels.

Generally you can get around on plentiful and inexpensive taxis or transit systems. China is building metros (subways) in many cities. Shanghai has the longest Metro system in the world, while Beijing ranks second. Distances between stations are often quite great and it is advisable to use taxis from the station for destinations that are beyond comfortable walking distance.

Getting Around Between Cities

Airlines: China also has an effective intercity transportation network. China’s domestic airline passenger volume is nearly equal to that of the European Union and trails the United States by 40 percent. Generally, the Chinese airline system is very "English friendly," with onboard staff generally bilingual and English speakers easily found within airports. Meals are provided on most flights.

Air tickets may be readily purchased using credit cards through Internet sites such as Orbitz.com, Expedia.com, Travelocity.com, and C–Trip.com. My favorite is C-Trip, a Chinese travel agency which has an English language toll free number in China.

Trains: China has the longest high-speed rail system in the world, with similar quality to those of Japanese and Europe or Amtrak’s Acela Express. The high-speed trains have train number prefixes of "C", "D" or "G" (such as G-1234). Other trains could be less comfortable for Westerner. They can be much slower and often do not have Western style toilets.

Announcements and electronic signs in carriages are in English and Mandarin. Staff is generally less English proficient than on the airlines, however. There is limited food service (as on the French trains) and travelers may want to take along snacks. Drinks are readily available.

Tickets may be purchased online from sites such as Travel China and C-Trip with credit cards. However, credit cards cannot be used for tickets at railway stations. I purchase tickets in China, at major stations, where there are special English windows.

Buses: Buses, which operate on the world’s largest motorway (freeway) network, go many places that cannot be reached by the higher quality train services. Often hotels will be able to obtain bus tickets. My most notable bus trip was from Ningbo to Shanghai, to cross the Hangzhou Bay Bridge, one of the longest in the world.

Hotels

China has its share of five star and other "high- end" hotels. I tend to avoid these hotels, because I am interested in stretching my dollar to see more, and stay longer. There are good options for lower cost hotels in China. My own favorite is Ibis, part of the French owned Accor chain. While the guest can expect to pay €100 or more in Europe, Ibis hotels tend to cost between $25 and $50 per night for double occupancy. The advantage, is that Ibis provides a consistent standard that is little different between Paris and Shanghai or Qingdao. Generally, Ibis staff communicates adequately in English. Ibis also has restaurants with limited fare, though I prefer the small entrepreneurial neighborhood establishments.

A good second choice is the locally owned Jin Jiang Inns, which have similar costs, but where staff English proficiency is less predictable. Even so, Jin Jiang Inn staff will often provide assistance using "on-call" English speakers by mobile phone.

The travel site Kayak.com aggregates hotel rates (including Ibis and Jin Jiang) and is a good shortcut for finding the best deals.

Eating

There is significant variation in the cuisine between the provinces and regions of China. Eating is one of the great pleasures of China. This too can be inexpensive. There are small independently owned restaurants throughout Chinese cities. Meals can be purchased at from $1 to $3 in these establishments. Of course, you can pay much more.

My favorite is Lanzhou noodles, which are served in a large bowl with beef, vegetables and hot Sichuan pepper sauce. Servers will routinely ask Westerners whether they want the hot sauce (and it is hot), but I order it. The noodle dish is named after the city of Lanzhou, capital of Gansu province.

However, some tourists may prefer Western food, which can be found at some higher cost restaurants and the many fast food restaurants such as McDonald’s, Burger King, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Pizza Hut.

Convenience Stores

Chinese cities are dotted with many small entrepreneurial as well as franchised convenience stores (or small grocery stores). Usually within walking distance, these stores carry a good selection of soft drinks, including both western and Chinese.

Currency

The Chinese currency is the "Yuan" or "RMB." The current exchange rate is about six to the dollar or 600 per $100. Money may be exchanged on entry at the airports and generally at the large national banks, such as the Bank of China, the Agricultural Bank of China, the China Construction Bank, the China Merchants Bank, the Bank of Communications, China CITIC Bank, and ICBC (Industrial and Commercial Bank of China). Usually, there will be English proficient staff available. These banks have branches throughout the nation. Further, these banks usually have Automatic Teller Machines linked to international networks, such as Visa.

Other Cautions

Water: As in many developing countries, tap water may be insufficiently safe for drinking. Hotels routinely provide bottled water.

Food: I recommend eating only hot food. It is advisable take along an antibiotic prescription in case of serious stomach upset. On 11 trips, I have had only one occurrence and have seen the problem cleared up overnight.

Taxis: The great majority of Chinese taxis operate legitimately, charging metered fares (with drop charges ranging from near $1 to just over $2). My fare from Pudong International Airport to the Jing’an District of Shanghai (beyond the core) was $32 in terrible traffic.

However, there can be difficulties with taxis, especially at train stations and airports. It is always best to obtain a taxi from the organized taxi rank, where metered fares will be available. Often western travelers are approached by drivers at terminal exits offering absurdly high rates. For example, this trip, at Longyang Road Station in Shanghai (terminus of the Mag Lev), I was offered fares ranging from more than three to 15 times the meter fare to nearby hotels.

The First Trip

A good way for the novice traveler to China to start is a trip to the Shanghai or Beijing areas.

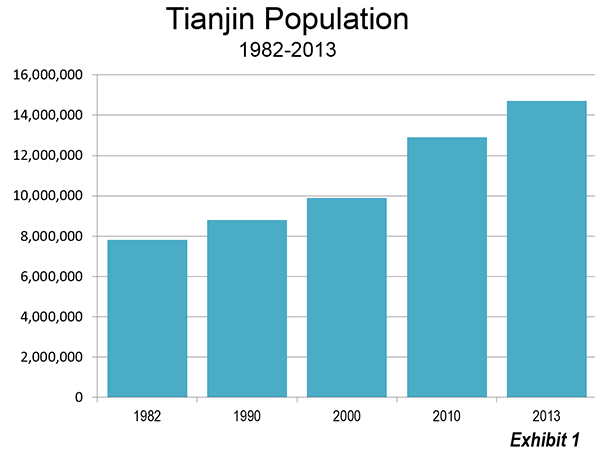

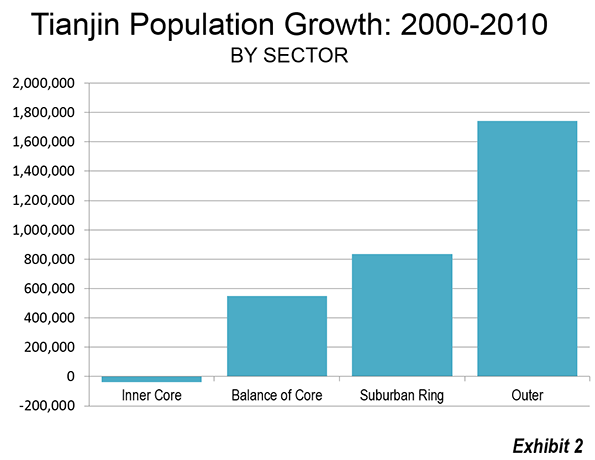

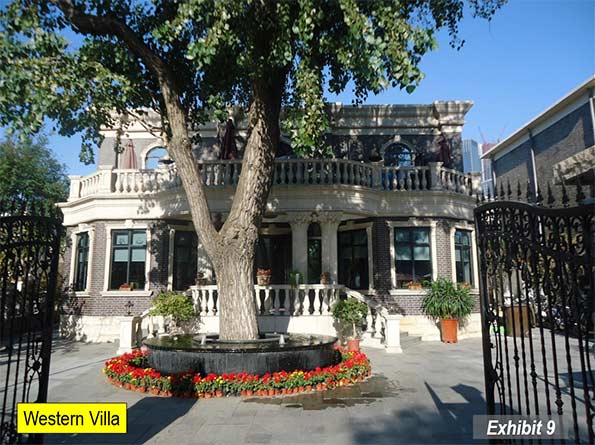

In Beijing, there are sites such as the Great Wall of China (Exhibit 1), the Forbidden City (Exhibit 2), the Ming Tombs. The Lama Buddhist Temple and the Confucius Temple (only a 3 minute walk away) and the Summer Palace. The former treaty port of Tianjin, with its extensive pre-War western housing and spectacular new architecture is little more than a half hour away by train. Tangshan, site of one of the world’s most deadly earthquakes (1976), is another 45 minutes away (Exhibit 3).

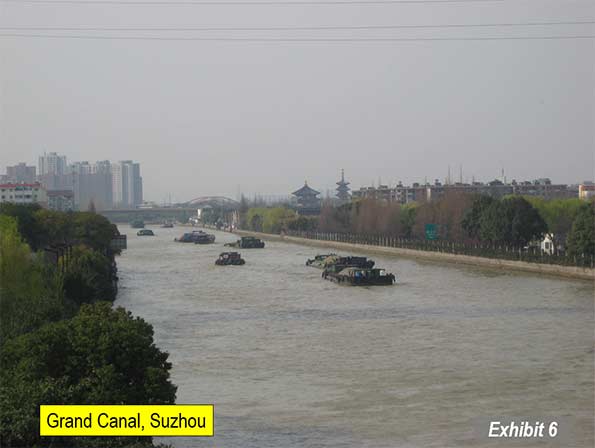

Shanghai has the "Bund," along the Huang Pu (river), with its Western style commercial buildings from the pre-World War II era. From the walkway on the Bund, there is a stunning view of the new Lujiazui business district in Pudong, which includes the second tallest building in the world (top picture). Only 30 minutes away by train is Suzhou, the "Venice of China," with its canals (Exhibit 4) and the leaning pagoda on Tiger Hill. Hangzhou, with its scenic West Lake is just an hour’s train ride away (Exhibit 5). The historic Grand Canal, which provided access between the Yangtze Delta and the Beijing area, can be seen at both Suzhou (Exhibit 6) and Hangzhou.

There are many other cities of great interest for subsequent trips, especially Chongqing, Qingdao, Xi’an, Dalian (Exhibit 7), Harbin, Chengdu, Shenzhen and Wuhan.

The bottom line is that traveling in China is more complicated than traveling in Wisconsin or Ontario. But it is not that difficult and getting better.

Note 1: The Mag Lev line was intended as a demonstration line that would encourage China to use that technology for its high speed rail network. Further, the line was to be expanded through central Shanghai and then southwest to Hangzhou (180 miles or 110 kilometers). Citizen opposition led to cancellation of the extension and China opted to use conventional technology, rather than Mag Lev for its high speed rail network.

Note 2: On Nanjing Road, Western tourists are often solicited by students to attend a tea drinking ceremony. This experience should be avoided. The tourist will have to pay the bill and the costs will likely be far above expectation.

Top photo: Lujiazui business center in Pudong, across the Huang Pu from the Bund (November 3 by author)

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.