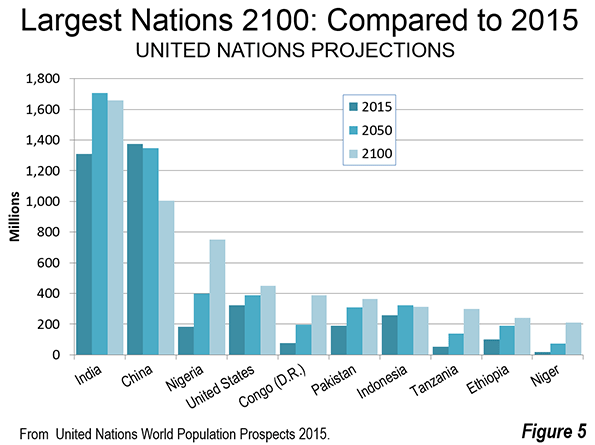

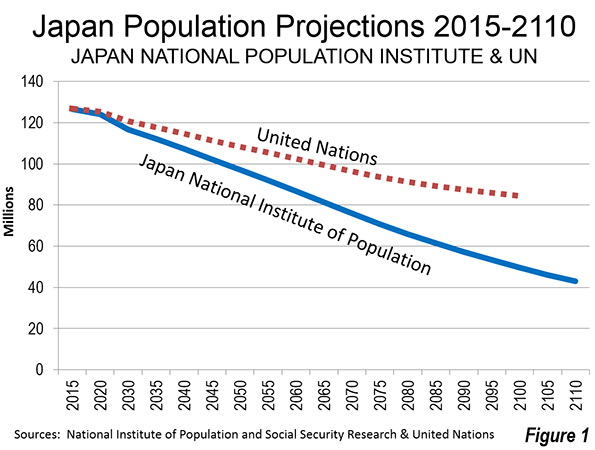

Japan reached "peak people" in 2011, when its population reached 127.4 million residents. From that point, all trends point to significant population losses. But, there is by no means unanimity on the extent of those population losses. Population projection is anything but an exact science, and Japan provides perhaps the ultimate example.

Dueling National Population Projections

Japan’s agency responsible for projecting population, the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research forecasts a stunning reduction of population to only 42.9 million residents in 2110. For every three Japanese residents today, there will be one in 2110 according to the National Institute of Population. If this projection is realized, Japan’s population would drop to a level not seen since the middle 1890s.

The National Institute of Population projects a population loss to 97.0 million residents by 2050, for an annual population loss rate of 0.7 percent from 2015. By 2100, the population would fall to 49.6 million, for an annual loss rate of 1.3 percent. Over the 95 years from 2015, the annual population loss rate would accelerate from 0.4 percent annually to nearly 1.5 percent.

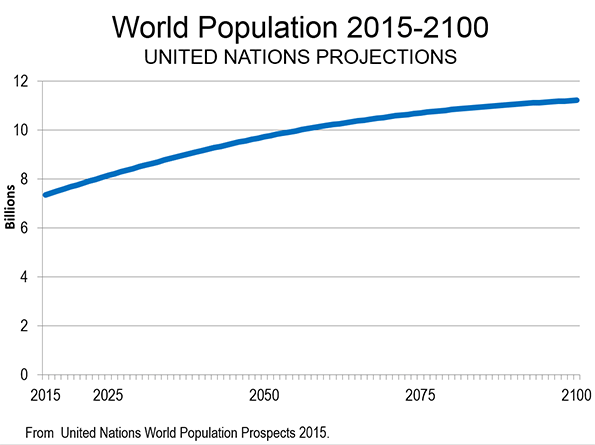

The United Nations is considerably more optimistic about Japan’s future population than the National Institute of Population. The UN forecasts a population of 108.3 million residents by 2050, or 11 million more residents than expected by the National Institute of Population. The annual loss rate is 0.4 percent, one half the rate projected by the National Institute of Population. By 2100, the last year of the UN series, the population would be 84.5 million, 35 million more than the National Institute of Population figure. The UN’s annual population loss rate would be 0.8 percent (Figure 1).

Major Metropolitan Areas

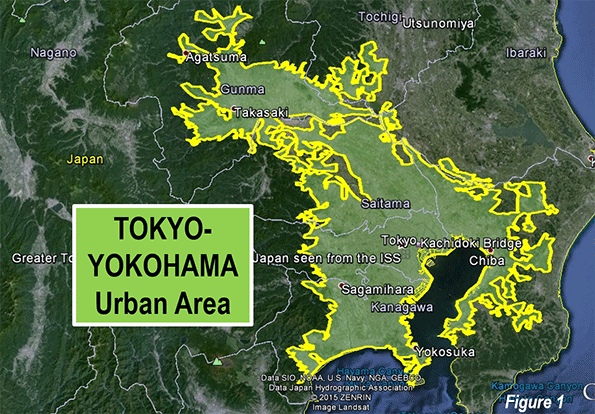

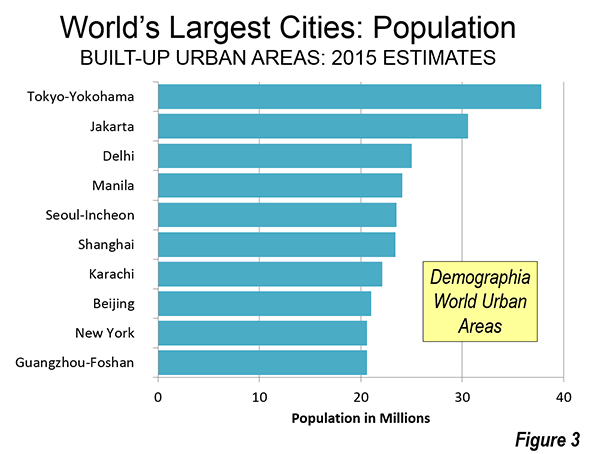

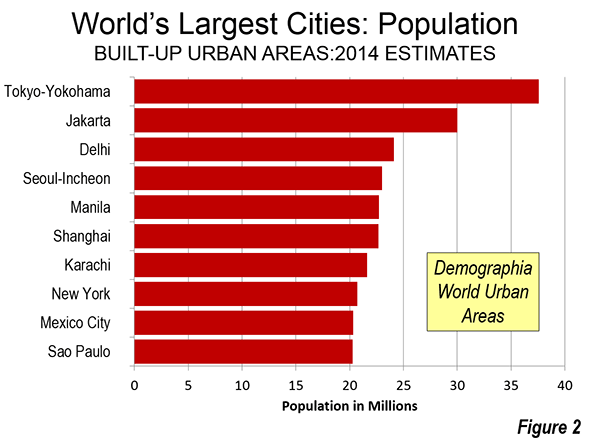

Much of Japan’s urban population is in the dense corridor from Tokyo-Yokohama to Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto, a distance of approximately 300 miles (500 kilometers). The four metropolitan areas of this corridor (Tokyo-Yokohama, Shizuoka-Hamamatsu, Nagoya, and Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto) contain approximately 75 million residents. By comparison, the US Northeast Corridor is about 1.5 times as long and has under 50 million residents.

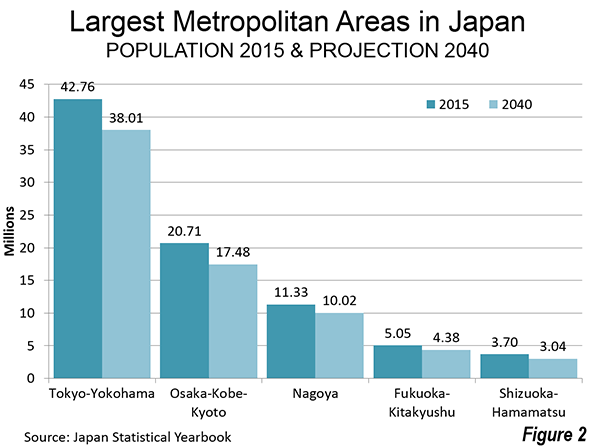

According to National Institute of Population data, each of the 10 largest metropolitan has reached its population peak. The most populous, Tokyo-Yokohama is the only major metropolitan area to have gained population between 2010 and 2015. Each of the others had already reached their population peaks, according to the forecasts that end in 2040 (Figure 2).

Tokyo-Yokohama:Tokyo-Yokohama is the world’s largest metropolitan area (labor market area). Much of it is located on the Kanto plain that stretches in three directions from Tokyo Bay. Between 2010 and 2015, Tokyo-Yokohama grew from a population of 42.6 million to 42.8 million. However a strong turnaround is anticipated. By 2020, the population is expected to fall to 42.4 million. Tokyo-Yokohama is expected to decline to 38.0 million residents in 2040, a reduction approximately equal to the population of metropolitan areas such as Phoenix, Montréal, and Melbourne. The 2040 population would represent a loss of approximately 11 percent from 2015.

Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto: Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto has been Japan’s second largest metropolitan area for decades. Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto is a true conurbation, with three separate core cities and their suburbs that have grown together to form a single urban area, which now also encompasses smaller Nara, the country’s ancient capital. Some of Japan’s most important historical sites are in Kyoto and Nara. Despite having less than one half the population of Tokyo-Yokohama, Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto has been one of the world’s largest metropolitan areas for at least the last half of the century. Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto’s population fell from 20.9 million in 2010 to 20.7 million in 2015. By 2040, this large urban agglomeration is forecast to have a population of 17.5 million, down 16 percent from its 2015 level.

Nagoya: Nagoya is Japan’s third largest metropolitan area and is located about two thirds of the way between Tokyo-Yokohama and Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto. Nagoya is renowned as the headquarters of Toyota. Nagoya is expected to fall from its 11.3 million residents in 2015 to 11.2 million in 2020 and 10.0 million in 2040. This population loss rate would be similar to that of Tokyo-Yokohama, at approximately 11 percent.

Fukuoka-Kitakyushu: The Fukuoka-Kitakyushu metropolitan area is comprised of two large and separate urban areas. It is the only metropolitan area of the largest five that is not in the Tokyo to Osaka corridor. Further, Fukuoka-Kitakyushu is on the island of Kyushu, to the south of the main island of Honshu. Fukuoka-Kitakyushu had a population of 5.0 million in 2015 and is expected to fall to 4.4 million in 2040. This is an approximately 12 percent population loss rate, somewhat worse than Tokyo-Yokohama and Nagoya.

Shizuoka-Hamamatsu:The Shizuoka-Hamamatsu metropolitan area is located between the Tokyo-Yokohama and Nagoya metropolitan areas. In 2015, the population was 3.7 million, which is expected to drop to 3.0 million in 2040. This area, long a critical part of Japan’s industrial complex, would suffer the largest loss among the five largest metropolitan areas, at 18 percent.

The Rest of Japan: The balance of Japan would experience an even greater loss, dropping from 43 million in 2015 to 34 million in 2040. This would represent a decline of 20 percent.

Japan: Leading the Way?

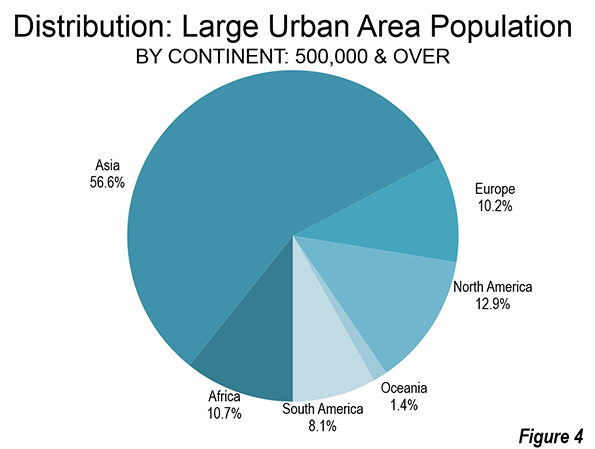

Japan is just the first of a wave of nations that are expected to experience population declines. The challenges are likely to be great as the nation is forced to downsize its considerable infrastructure to accommodate a smaller population. With a growing imbalance of senior citizens relative to working age adults, there are likely to be significant difficulties in financing social services. Japan’s strategies and successes or failures will be watched closely by national leaders from Berlin to Beijing and Brasilia whose nations are likely to experience reductions in population and demographic imbalances starting mid-century or sooner.

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.

He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Fukuoka (by author)