The "urban scaling" research of Geoffrey West, Luis Bettencourt, Jose Lobo, Deborah Strumsky, Dirk Helbing and Christian Kuhnert on cities has attracted considerable attention (references below). They have provided strong quantitative evidence, based upon voluminous econometric analysis that cities tend to become more efficient as they grow in population.

Specifically, West, a theoretical physicist, and his team show that measures such as gross domestic product per capita and income per capita rise, on average, 15 percent with each doubling of city population. They draw parallels with the animal kingdom, noting that larger animals tend to be more efficient than smaller ones, and comparing elephants, efficient because of their size, to cities.

This is all very attractive, especially the elephant analogy, which appropriately suggests that cities are organisms.

The Urban Organism

Yet the research has been widely reported to suggest that density as opposed to size is the key to urban productivity. West et al look at cities as "integrated economic and social units," at the "level of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs); in the European Union, larger urban zones (LUZs); and in China, urban administrative units." This is the economic, or functional manifestation of the urban organism (the urban area, the area of continuous urbanization, is the physical manifestation). In so doing, West, et al demonstrate a familiarity with urban geography that is all too rare, even among analysts who have studied cities for far longer.

The key issue here is what constitutes a “city”. New York is a good, example, as headquarters to the national media, a world class city and as urban as it gets in the United States. But the New York metropolitan area, the "integrated economic and social unit" is not Manhattan or even five boroughs. It stretches from a bit west of Blooming Grove Township, in Pike County 25 miles west of Port Jervis, a city 90 miles from Manhattan located in western Orange County, NY, to Montauk Point in Suffolk County and from north of West Point, in Putnam County to Egg Harbor Township, in Ocean County, New Jersey (that’s nearly 30 miles south of Toms River). Suffice it to say most of this vast region is not dense at all.

Divining Density

Yet, some analysts have characterized the West, et al research as being about higher densities, Richard Florida wrote in The Wall Street Journal:

Researchers at the Santa Fe Institute have been able to demonstrate that bigger, denser cities literally speed up the metabolism of daily life.

That’s only half right. The research was about city size, not density, as the authors indicate (below).

All too typical of the way that suburbanized America is disparaged by the media, Jonah Lehrer, of The New York Times sputtered that:

In recent decades, though, many of the fastest-growing cities in America, like Phoenix and Riverside, Calif., have given us a very different urban model. These places have traded away public spaces for affordable single-family homes, attracting working-class families who want their own white picket fences.

In reality, the kind of suburbs found in Phoenix and Riverside-San Bernardino will be found surrounding every one of the nation’s core cities, including New York, an urban area that covers more land area than any urban area in the world at 3,450 square miles (8,935 square kilometers), according to the Census Bureau. That’s twice the expanse of the Los Angeles urban area. Granted, New York’s Hudson Valley suburbs are greener and more affluent than most in Phoenix, but their population density is nearly the same. Moreover, neither Phoenix nor New York (think Staten Island or much of Long Island) should be ashamed of attracting "working class families who want their own white picket fences." Why demean aspiration?

Urban blogger James Withow refers to their "remarkable findings" that "raise interesting policy issues on density." Another analyst wrote "West offers data that shows cities create economies of scale that suburbs and small towns cannot match." This is patently absurd since, as noted above, West did not study any part of the urban organism below the metropolitan area. There was no attempt to make a distinction between the productivity of say, Manhattan or Brooklyn, to White Plains or even Blooming Spring Township. No core city or suburb is an "integrated economic and social unit."

West et al on Density

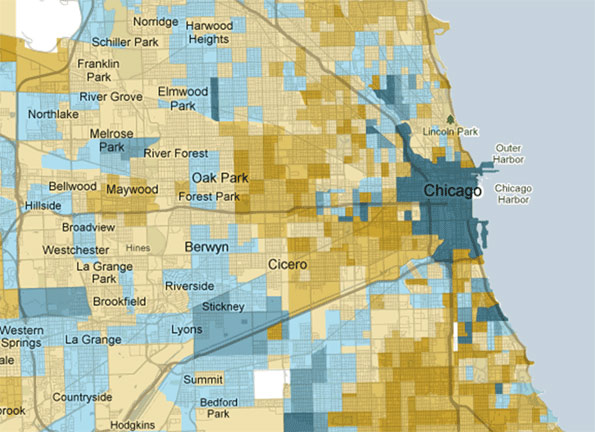

Indeed, West et al make it very clear that their findings have nothing to do with urban population density. They tested for correlations population growth and income, patents and violent crimes, and found "no significant trend exists between residuals for income, patents and violent crime and population growth or density." They further note their equations showed an "R2 consistent with zero" (in every day English, that means they found no relationship between density and the other variables).

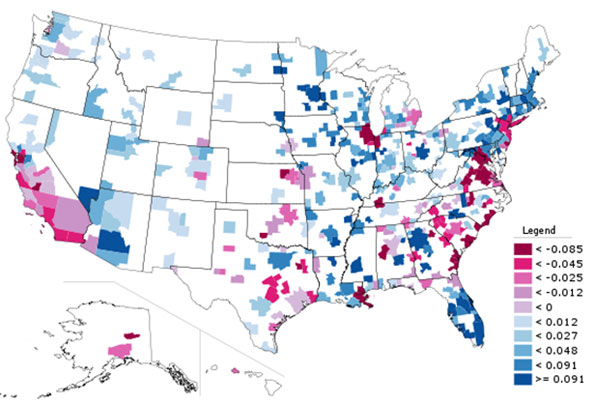

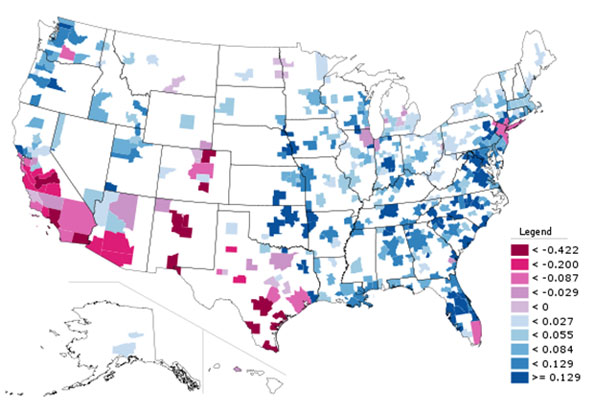

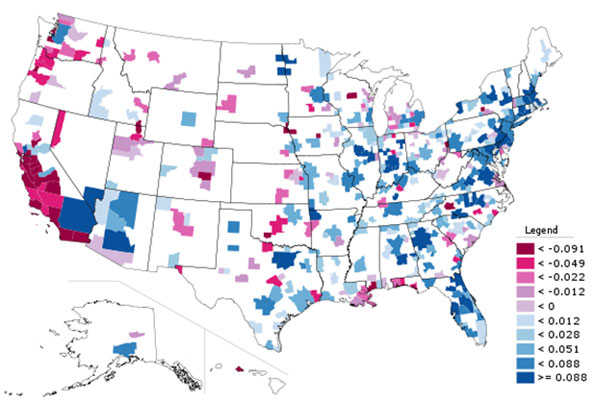

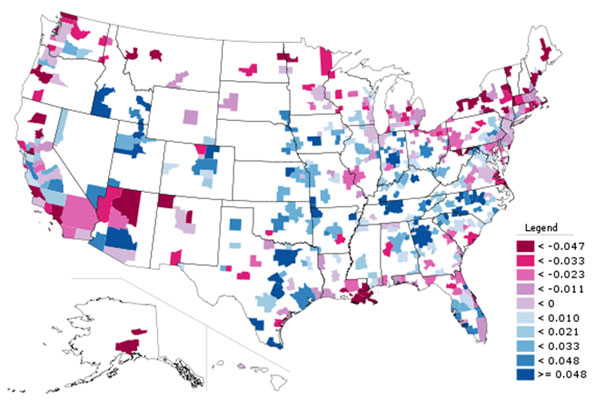

This conclusion was correct, though comparing metropolitan area densities is less than ideal. Just to check, we reran the equations with urban density data and found that this approach too produced an "R2 consistent with zero," not only for income, patents and violent crimes, but also gross metropolitan product.

West et al pointed out that:

The shape of the city in space, including for example its residential density, matter much less than (and are mostly accounted for by) population size in predicting indicators of urban performance. Said more explicitly, whether a city looks more like New York or Boston or instead like Los Angeles or Atlanta has a vanishing effect in predicting its socio-economic performance. (emphasis by author)

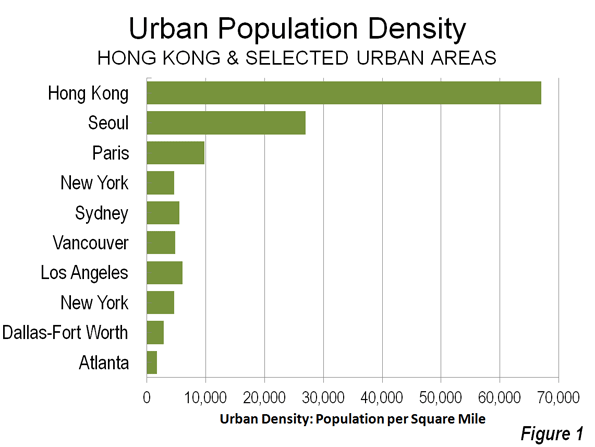

In other words, the same improvement in urban performance would be predicted from doubling the population of Atlanta, with an urban density of 1,700 per square mile (700 per square kilometer) as in New York, with more than three times Atlanta’s density or Los Angeles’ with more than four (Los Angeles is highest density large urban area in the United States).

It turns out – counter the misunderstandings of some urbanists – that higher or lower density simply does not matter according to the West, et al research.

It’s About Density Thresholds and Efficient Labor Markets

Cities (integrated economic and social units) are created by reaching urban density thresholds. They tend to become more productive as they grow, so long as they are not too large to function as a labor market. Density doesn’t matter particularly. Indeed, the general tendency is for cities to become more dispersed (less dense) as they grow, as indicated by longer term data in the US, Canada and around the world.

For example, the Seattle and Houston urban areas have population densities much lower than those of Paris, London, Hong Kong and even Los Angeles – yet they still rank higher among the most productive metropolitan areas in the world, according to the Brookings Institution Global Metropolitan Monitor 2011. Brookings rates Hartford as the most productive metropolitan area in the world, yet its urban population density is nearly as low as Atlanta’s.

Finally, the Brookings list excludes the world’s most dense major city, Dhaka. That’s because the economic output of its 15 million people is insufficient to make a list that includes cities one-tenth its size. Dhaka combines the highest population density in the world with perhaps the lowest per capita economic output of any megacity in the world.

Allowing Organisms to Grow

As West et al suggests, cities, like elephants, are organisms. Both expand (dare we say "sprawl") as they grow. This should be cause for concern, given planning dictates that would restrain urban organism, such as urban growth boundaries. These restraints are akin to depriving a large mammal of sufficient space to roam and feed. That’s no way to treat a productive organism, or a great city.

——-

Reference Materials:

Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities

Urban Scaling and Its Deviations: Revealing the Structure of Wealth, Innovation and Crime across Cities

2010 US Urban Area Data

——-

African Bush Elephant photo by flickr user nickandmel2006.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”