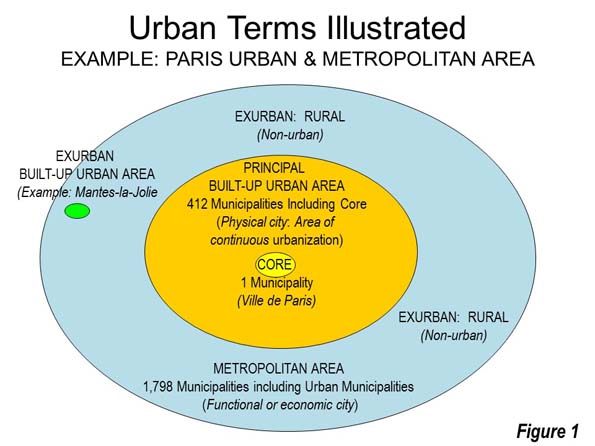

Many of the world’s biggest cities are getting bigger still. In 2017, the number of megacities — urban areas with better than ten million people — increased to 37 in 2017, as the Chennai urban area entered their ranks. Chennai becomes India’s fourth megacity, along with Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkota. These are among the major findings in the just released 13th annual edition of Demographia World Urban Areas, which provides population, land area and population density estimates for the 1,040 identified built-up urban areas (cities) in the world. Built-up urban areas are the physical form of the city, a definition which separates out the urban, or constructed form of the city from the rural and smaller town areas with which they form a metropolitan area or labor market (Figure 1).

The World’s Largest Cities

Asia increasingly dominates the ranks of the world’s most populous cities. Tokyo-Yokohama continues to be the largest urban area in the world (Figure 2), a ranking it has held for more than six decades. It is estimated the Tokyo Yokohama house a population of 37.9 million, living in approximately 3300 square miles (8,500 square kilometers) with a population density of 11,500 per square mile (4,400 per square kilometer).

Jakarta is the second largest urban area, with a population of 31.8 million 9,600 per square kilometer). Delhi, India’s capital held onto third position, with a population of 26.5 million. Delhi has now opened up a more than 3.5 million lead on 8th ranked Mumbai, which had been India’s largest urban area before and which some experts had considered likely to become the world’s largest city. This prediction, like a similar ones made with respect to Mexico City in the 1980s has not come to fruition and it seems unlikely that either urban area will ever be, the world’s largest.

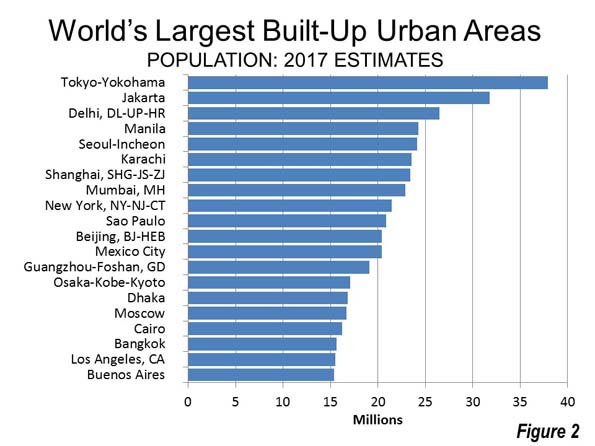

Manila moved up from fifth position to fourth position, passing Seoul-Incheon (Figure 3). Manila’s population is estimated at 24.3 million, in an area of 690 square miles (1,790 square kilometers) in a population density of 35,100 per square mile (13,600 per square kilometer), the highest density among the top five built-up urban areas.

Seoul-Incheon remains the only high income city, besides Tokyo, in the top five. Seoul-Incheon is estimated to have a population of 24.1 million and an urban population density of 22,700 per square mile (8800 per square kilometer).

The second five includes Karachi, Shanghai, Mumbai, New York and Sao Paulo, with only New York in the high income world. Thus, seven of the largest 10 cities in the world are now outside the high income world. New York was the largest city in the world from the 1920s until the mid-1950s. London, which was the largest city in the world from the early 19th century to the 1920s is now ranked 34th, while Beijing, which preceded London as largest ranks 11th. Among the next ten largest urban areas, only two — Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto, at 14th and Los Angeles, at 19th are in the high-income world. Formerly rapidly growing Los Angeles seems likely to drop out of the top 20 before long.

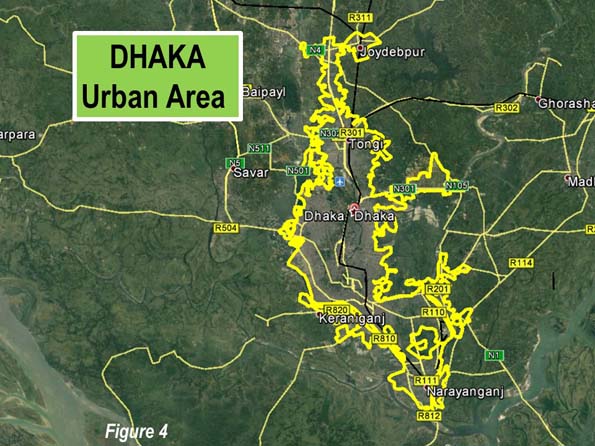

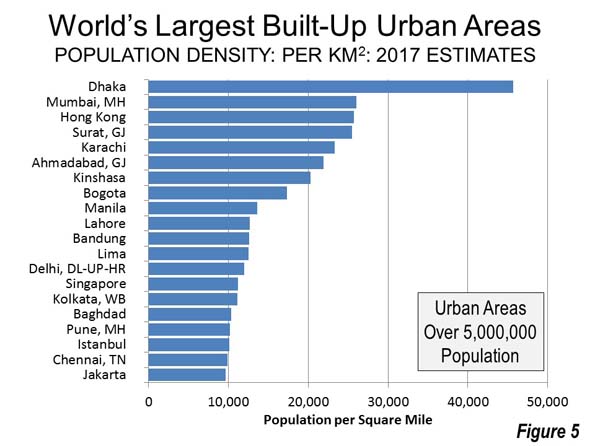

Dhaka’s High Density

Dhaka (Figure 4) remains far and away the highest density built-up urban area in the world (Figure 5), Dhaka has an urban density of 118,500 per square mile (45,700 per square kilometer). No other urban area exceeds 70,000 per square mile (27,000 per square kilometer). Yet, Dhaka is not dense enough for some critics, who perceive it to sprawl too much. Notably, Dhaka is about 50 percent denser than Mumbai or Hong Kong (the high income world’s densest city) and more than 30 times as dense as international densification model Portland, Oregon. Portland ranks 963rd in population density out of the 1040 built-up urban areas.

A Half Urban World?

In recent years, the population of the world has become majority urban for the first time. Yet, most people do not live in the largest urban areas. For example, only 15 percent of the urban population resides in the 37 megacities. The middle of the urban population distribution is at a population of approximately 680,000. People who live in urban areas such as Shizuoka (Japan), Mangalore (India), not to be confused with Bangalore, Qitaihe (China) and Allentown (United States) are the average. The population of the urban areas that are larger have half of the urban population, while the smaller includes the other half.

Distribution of the Population

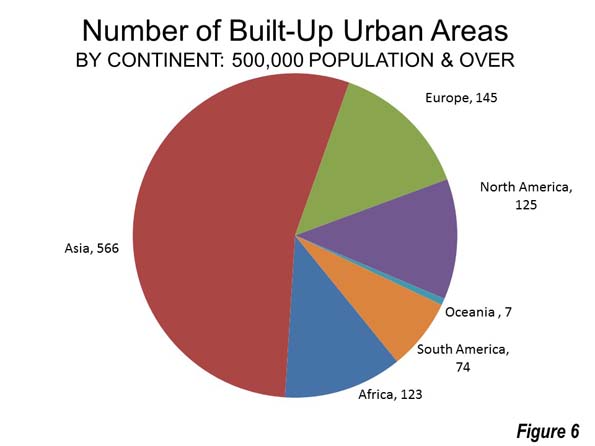

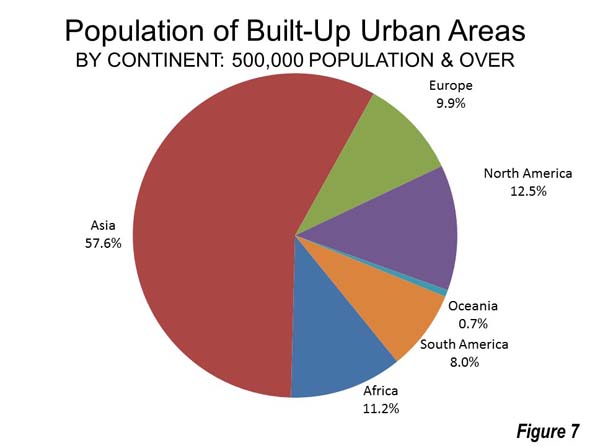

World urbanization is dominated by Asia, which has a majority (54 percent) of the built-up urban areas with at least 500,000 population. Asia’s dominance is even greater in population, with 58 percent of the residents in urban areas of 500,000 or more. North America has the second largest share of urban area population, at 12.5 percent, followed by Africa (11.2 percent) and Europe (9.9 percent). By contrast, Europe has the second largest number of urban areas of 500,000 population or more, reflecting the generally smaller population of its cities (Figures 6 and 7).

Concentration of Future Growth in Asia and Africa

The latest data underscores the substantial changes that have occurred in urbanization in recent decades. In 1950, 11 of the 20 largest cities were in the high income world, according to the United Nations. On average these cities had 5 million population. Today, only five of the 20 largest cities are in the high income world and their average population is 21.5 million.

In the decades to come, Asia seems likely to continue its dominance, while Africa will capture an increasing share of urban population growth. By 2050, the United Nations projects that approximately 1.2 billion residents will be added to Asian urban areas, while nearly 900 million will be added to the urban areas of Africa. This would leave only about 125 million, or five percent of total urban growth for the rest of the world. Of course, projections can be wrong, but the strength of current trends make these forecasts all the more credible.

Note: Demographia World Urban Areas uses base population figures, derived from official census and estimates data, to develop basic year population estimates within the confines of built-up urban areas. These figures are then adjusted to account for population change forecasts, principally from the United Nations or national statistics bureaus for a 2016 estimate.

Built-up urban areas are continuously built-up development that excludes rural lands. Built-Up urban areas are the city in its physical form, as opposed to metropolitan areas, which are the city in its economic or functional form. Metropolitan areas include rural areas and secondary built-up urban areas that are outside the primary built-up urban area. These concepts are illustrated in Figure 1 (above), which uses the Paris built-up urban area (unité urbaine) and metropolitan area ("aire urbaine") as an example.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Cover of Demographia World Urban Areas: 13th Annual Edition.