Known for her spiky hair, studded-collar and heels, Sydney’s Lord Mayor is the epitome of progressive chic. For a green activist, though, Clover Moore attracts some surprising company. Landlords owning 58 per cent of the CBD’s office space have rushed to join her Better Buildings Partnership, an alliance “to improve the sustainability performance of existing commercial and public sector buildings”. At first glance, the property industry’s enthusiasm for ‘green building’ seems strange. Shouldn’t they be insisting on less costly design and materials? Or despite their hard-nosed reputation, are they out to save the planet after all?

As it turns out, the lure of green building has more to do with cash than climate. By virtue of the soft economy and creeping “sustainability” measures, green-rated office towers are a gilt-edged opportunity for investors fleeing stocks and bonds. The wave of change rolling over central Sydney displays a certain logic. Meddling officials get to wrap themselves in virtue while big landlords – local and global investment trusts and fund managers – get a new premium grade rating for their properties. How better to protect asset values in an unsettled world? It’s a cosy, CBD-boosting deal, even if it distorts job and investment flows in outlying parts of the city.

The floor-space revolution

Even before the crash of 2008, banks, insurance companies and other financial services were under pressure to extract higher value out of every inch of floor-space. The global debt meltdown only accelerated the process. Aggressive cost-cutting saw Australian banks reduce their cost-to-income ratios from around 60 per cent in the late 1980s to around 45 per cent today. This priority is turning Sydney CBD’s office core inside-out, a trend reinforced by pay-offs from the green-rating of building stock.

One recent headline summed it up neatly: “Martin Place exodus”. The article describes how major banks like Westpac, ANZ and Commonwealth are all vacating large office blocks in stately Martin Place, “the heart of Sydney’s financial centre”. Linking George Street, the CBD’s commercial “spine”, to the city’s government office sector along Macquarie Street, near state Parliament House, Martin Place has hosted the cream of Australia’s banking and insurance houses since the nineteenth century. The Reserve Bank is based there as well.

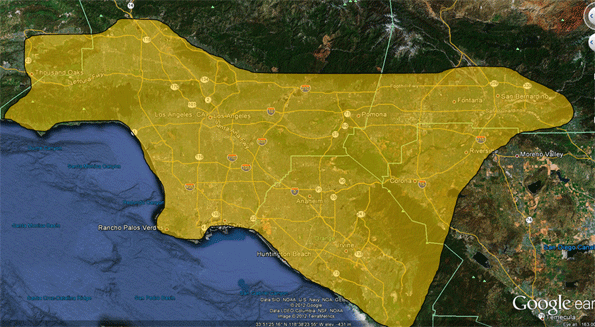

Sydney’s traditional office core enclosed Martin Place within Clarence, King and Macquarie Streets and the waterfront at Circular Quay. In line with conventional CBD morphology, this lies just north of the longstanding, but expanding, retail core bounded by York, Park, Elizabeth and King Streets, where large department stores are concentrated around the conjunction of George and Market Streets, the CBD’s peak land value intersection (PLVI).

Driven to economise on floor-space, larger financial and professional services firms are leaving the traditional office core for outer blocks, which until recently were, in the parlance of CBD theory, “zones in transition”, low-grade areas on the periphery of the office and retail cores with potential for higher value functions. Some “see the axis of the Sydney central business district changing.” Typically, landlords are now expected “to work with Sydney tenants to address their concerns around relocating or redesigning … and help minimise costs and increase efficiencies in their work environment.” Lest this be dismissed as penny-pinching, a new “workplace philosophy” has been invented to sell the floor-space revolution, and, predictably, that old chestnut “sustainability” has been pressed into service.

Spreading from banks to insurance companies to professional services and other large white-collar workplaces, “activity-based working” (ABW) has been treated to rapturous media coverage. “Gen Y shuts door on open-plan century”, is how one headline put it. In progressive outlets, ABW is depicted more as a reaction than an initiative, a revolution forced on employers – and indirectly on property developers – by green, socially aware, tech-savvy Gen Y office workers. As the narrative goes, they reject confinement in the “assigned desks” of open-plan workstations or offices.

At one prominent bank, staff are “free to roam and work where and how the mood takes them.” Usually, we are told, “they start the day at an ‘anchor point’ where their locker is and which they share with about 100 other workers … they might stay around that area for the day, with a choice of work situations ranging from quiet spaces to conversation areas, or they may set up somewhere else depending on who they need to see.” Equipped with laptops, i-pads, mobile phones and wi-fi, they “can move from space to space and hardware isn’t an inhibitor.” Some organisations “have been … expanding a whole range of tools from [their] internal social-media platform to crowd-sourcing …” Spaces come in all varieties, including meeting rooms, “hush” rooms, discussion pods, team tables, cafes, “floor hubs”, “touch-and-go area[s] for short stays”, even “funky kitchens”.

And topping off the semblance of a white-collar wonderland, ABW adapted buildings often have glass lifts and “a central atrium allowing views to other floors”, so “you really do feel part of a bigger whole, you can see everybody.”

Touted in near-utopian language, ABW unites the high-end circle of developers, architects, interior designers, building managers, real estate agents and progressive media. Most of all, we are assured, it’s about values, lifestyles and the coming generation, invariably presented as model progressives. According to a Colliers International report, Generation Y “prefer to work for an organisation with a commitment to social causes than one without … [i]n relation to the built environment, being green as an office occupier will become more of a ‘must have’ than a ‘nice to have’ in order to attract and retain staff.” Amongst other things, this means “creating less hierarchical workplaces, which facilitate collaboration, personal accountability and flexibility.”

Such are the times, that if a business announced ABW-type reforms to improve its bottom line, raise productivity or increase returns to investors, it would be damned as a “slave to neo-liberal dogma”. But if the very same measures were dressed-up in the garb of “sustainability”, it would be showered with awards and accolades.

Notwithstanding the pushy New Age rhetoric, ABW is more an economic-cum-technological opportunity for employers, than a revolt by the young and restless. Focus on costs is inevitable when economic conditions are so tight, and information and communications devices so ubiquitous and portable. A popular measure of office space efficiency is the workspace ratio, explains a researcher at Jones Lang Lasalle, or the number of square metres occupied by each office worker. The typical ratio is 15 square metres per person, but technology is freeing up workers to leave the office, so occupancy is typically now between 40 and 50 per cent, which translates, on average, to each worker occupying 37.5 square metres. “That’s expensive space”, he says.

Other research found that in a traditional office, between 55 and 85 per cent of desks are not used at any given time. Yet other studies indicate that “trading off individual territory for shared areas” can reduce floor space requirements by 20 to 40 per cent. This all leads directly to the bottom line. By cutting the amounts paid for rent and outgoings, says a Colliers researcher, ABW could reduce a firm’s total cost by up to 30 per cent.

That’s reason enough to drive large organisations out of their digs in Martin Place and the old office core, mostly for state-of-the-art towers designed to accommodate ABW floor-plans and facilities. “Macquarie Bank was an early mover (to Shelley Street), as was Westpac to its vertical campus in the western central business district”, report Jones Lang Lasalle on the major banks, and “[m]ore recently, the Commonwealth Bank has moved to Darling Quarter and ANZ will soon move to Pitt Street.” One way or another, the larger financial institutions, whose head-office functions were scattered throughout the CBD, have “implemented strategies to consolidate their space requirements and build in [ABW] flexibility.”

This isn’t happening to satisfy worker demands for “sustainability”, but recourse to “green ethics” no doubt helped prise the sceptical from their desks.

Green-star trek

Nor have landlords failed to gain from the floor-space revolution. Large and institutional players like real estate investment trusts and fund managers profited from a wave of demand for innovative, capital-intensive building stock. More unexpectedly, they encountered a rising class of green-tinged activists, designers and architects, whose obsessions with energy-saving and natural power came in useful. As climate change crept up the political agenda, progressives across all tiers of government soon turned to the built environment, churning out laws and regulations that defined and mandated ‘green building’ standards. The property industry’s peak bodies embraced the concept.

This is somewhat paradoxical. Despite its obsession with all sorts of metrics, ratios and indices, the property sector doesn’t seem to care that the object of these standards is unmeasurable. Their effect on the global climate system can never be known (it was always fanciful to suggest that Australian building styles would affect the climate, but anyone who believes it after Copenhagen, Cancun, Durban and Rio is deluded).

On the other hand, the financial benefits are rather more tangible. The key is NABERS, the National Australian Built Environment Rating System. Administered nationally by the New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, NABERS is a rating scale from a low of 1 to a high of 6 stars (the “Green Star”) applicable to buildings or tenancies, based on criteria like energy efficiency, water usage, waste management and indoor environment quality. The federal and some state governments have mandated at least a 4.5 star rating for public sector offices, and 4.5 has generally become the minimum for image-conscious corporates. A building or suite designed or refurbished for ABW will naturally score well.

The Commonwealth Bank’s new campus-style headquarters at Darling Quarter is in the CBD’s “western corridor”, formerly a “zone in transition” near the disused docks and freight yards of Darling Harbour. It achieved a coveted 6 star rating. Coming up with two curved-roof buildings of six and eight stories, “the designers have emphasised the natural light, air quality and water recycling … with features including a full-height atrium, single-pass ventilation, blackwater recycling, trigeneration power and passive chill beam air-conditioning.” Westpac’s new campus further up the corridor at 275 Kent Street achieved 4 stars, and the three towers underway at Barangaroo, a futuristic, mixed-use precinct at the corridor’s northern end, meet 6 star specifications. ANZ’s new headquarters at 242 Pitt Street (161 Castlereagh), towering over the CBD’s “mid-town” south of the retail core, also aims for 6 stars.

The most vaunted 6 star tower is the oval-shaped, “flagship” tower at 1 Bligh Street. Using 3D software called Building Information Modelling or BIM, the designers conceived an edifice with “gas and solar panels reduc[ing] electricity consumption by as much as 25 per cent, while water recycling reduces mains water by up to 90 per cent …” But its “principal sustainability feature is a fully glazed doubleskin façade made from clear glass panels … allow[ing] for automated sunshading that dramatically reduces the heat load on the building, which means [it needs] less airconditioning and can have … better natural light.” First-tier law firm Clayton Utz is the building’s anchor tenant.

To the extent that creative designers, developers and landlords have combined to meet a demand in the market, these buildings are impressive enough. That’s how markets should work. But on the pretext of “sustainability”, activist politicians and officials have, effectively, codified the product and marketing strategies of the most powerful players. NABERS does that by granting official recognition to a system mirroring the star scale long used in the hotel industry. Overnight, hundreds of thousands of square metres of non-rated office space was downgraded. Rent-seeking opportunities for the owners of rated space proliferated, to the detriment of smaller, more marginal players, their tenants and peripheral regions. “While the NABERS rating of a building is not the sole factor for corporate tenants”, said a CBRE director, “it is playing a significant role in selecting suitable office space.”

Clover Moore, whose jurisdiction covers capital-rich Sydney CBD and surrounds, has actively boosted the interests of large and institutional landlords with a grab-bag of lucrative benefits. There’s the CitySwitch Green Office program, which assists landlords leasing more than 2000 square metres of office space to achieve a mandatory NABERS rating; there are “green loans” for “sustainable retrofits” to be repaid as a levy on council rates; there’s a scheme under the Better Buildings Partnership that enables commercial property owners to enter Environmental Upgrade Agreements (EUAs) and share the cost of green building upgrades with tenants; and there are exemptions from a levy on new construction for green initiatives.

All in all, NABERS effects have proven a boon to the high-end property industry. Particularly for listed real estate investment trusts (REITs) and fund managers, but also many unlisted investors, which value stable capital growth as much as income, and continually trade or “recycle” assets to manage their portfolios. By allocating capital efficiently for market-oriented purposes, these investors can play a positive role in urban development, as long as green distortions (amongst others) don’t get in the way.

An Australian Property Institute study at the end of 2011 found that office buildings with a 6 star NABERS rating enjoyed a premium in value of 12 per cent, those with a 5 star rating 9 per cent, those with 4.5 stars 3 per cent, and those with 3 stars 2 per cent. In May 2012, the IPD green property survey found that “prime office buildings with high NABERS ratings – from 4 stars to 6 stars – outperformed the broader prime office market over the past year … the greener buildings delivered an 11.3 per cent total return compared with the overall CBD office return of 10.8 per cent.” Further, buildings with a high NABERS rating “significantly outperformed assets as having a NABERS rating of 3.5 stars or less … better-rated assets delivered 11.8 per cent compared with 8.7 per cent for the lower-rated properties.”

Capital growth conscious REITs and funds must have been pleased to hear, from a principal of the IPD Green Property Investment Index, that “owners who improve the sustainability attributes of their buildings are more likely to experience relatively stronger growth in capital values and will mitigate downside risk in asset values.” That’s a bonus for such local and global investors who have poured billions into the “safe haven” of Australian – especially Sydney – commercial real estate for other reasons, like the diminished standing of other asset classes, stock market volatility, a relatively sound economy, a reputable legal system and links to the booming Asia-Pacific region. Sydney was the world’s fourth most popular destination for cross-border property investment in the 18 months to June 2010, while the spreading use of NABERS culiminated in November 2011, when a rating became mandatory for space above 2000 square metres.

This is how a mayor can spend her life cultivating a progressive persona, only to end up the unwitting tool of some canny fund managers.

Regressive recentralisation

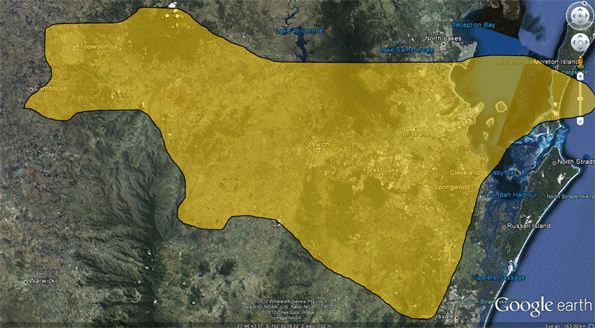

Green building is promising to be a goldmine for the well-placed, and a dead weight for almost everyone else. In an April 2012 Market Overview for Parramatta, a second-tier CBD servicing Sydney’s western region, Knight Frank explain that “the gap between economic rents and market rents remains a constraint on new [office] supply.” In other words the cost of land acquisition, planning and building processes, construction and fitting out, and a profit margin, on a square metre basis (economic rent) exceeds the rent obtainable from prospective tenants (market rent). Not all the gap between economic and market rents can be pinned on green standards, now essential for investor interest. But they are an undeniable factor. On one estimate, by consultants Davis Langdon, achievement of a 4 to 6 star NABERS rating can add between 3 and more than 11 per cent to construction costs.

If supply constraints are serious in Parramatta, where the federal and NSW governments have relocated several agencies and departments, apparently they are acute in more suburban locations. According to a newspaper report in April 2011, “the trend across the Sydney metropolitan markets is falling [office] supply … this is evident across all key markets including North Sydney, St Leonards, Parramatta, North Ryde, Rhodes and Homebush … at present there is no speculative development across these suburbs, so the problem of reduced A-grade space will only increase during the next couple of years, putting pressure on rents and incentives.” The only speculative office block started at the time was at Norwest, says the report, a specialised business park in north-west Sydney. The building was designed for a 4.5 star NABERS rating.

These weak conditions have various causes, but green standards shouldn’t be underestimated. Investors have lost interest in non-rated projects, and the economics of rated projects are trickier beyond high-rent centres like the CBD or business parks. According to a CBRE director, as of June 2011 there was “more capital looking to invest in the office sector than was evident before the global financial crisis … however, the majority of this capital is only chasing prime assets with very few groups willing to consider smaller secondary assets and non-central business locations.” For their part, more demanding tenants are also retreating to the green citadels and ABW theme-parks of Sydney CBD. Noting the CBD’s low office vacancy rate, Jones Lang Lasalle explain that “any downsizing that has occurred in the financial services sector has been offset by tenant centralisation … [a]s companies continue to look to improve the environment and amenity for staff as a means of attracting and retaining the best talent.” They detect a “trend to centralisation”. Similarly, a Colliers director observed that “tenants were being driven out of metro markets by tight vacancy rates for quality space and are attracted by a greater ability to attract and retain staff if located in the CBD.”

Phrases like “attract and retain staff”, of course, suggest NABERS rated buildings adapted for ABW. The portability of communications devices should be liberating workers from fixed locations, not just assigned desks. ABW advocates love phrases like “work is a thing you do not a place you go” and “work is becoming a process not a place”. But green imposts are having a countervailing effect.

This withdrawal of capital and tenants is bound to choke-off a range of suburban and peripheral businesses, the small to medium sized service operators, start-ups, microbusinesses, consultants, franchisees and sole traders which rely on freely-available space and low rents.

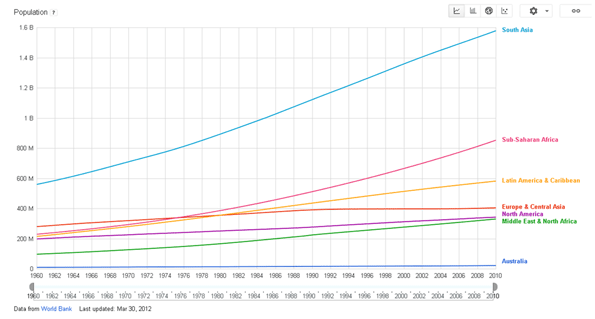

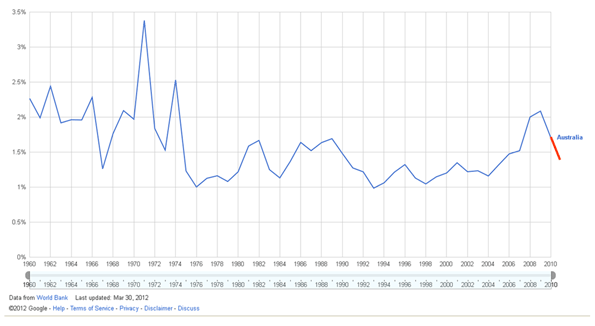

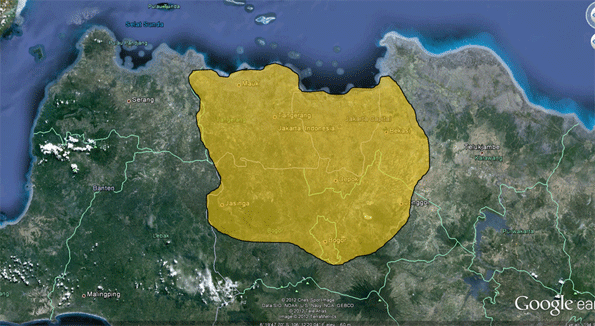

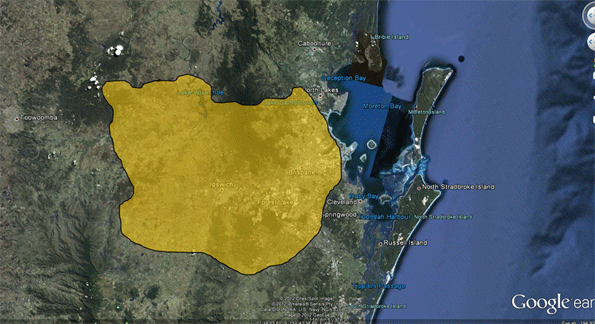

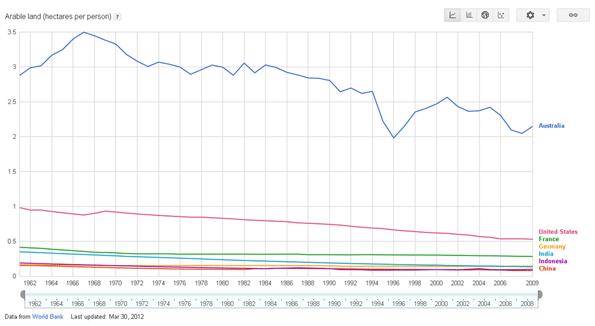

To all but the greenest ideologues, it should be clear that the decentralisation of offices – as well as factories and warehouses – over recent decades has fuelled Sydney’s prosperity, enabling the city to absorb an extra 1.5 million people since the mid-1980s. Equally, it should be clear that decentralisation offers better outcomes on access to affordable housing, traffic congestion and employment dispersion. On average, peripheral Local Government Areas (LGAs) still experience higher unemployment rates than central LGAs. That’s why the centralising forces unleashed by green planning and building codes pose serious dangers to economic vitality across the greater metropolitan region. Plenty of attention has been lavished on the pampered few in their ABW playgrounds. Some should be spared for the vast majority who seek to make a life in Sydney.

John Muscat is a co-editor of The New City, where this piece originally appeared.

Photo by Christopher Schoenbohm.