“The prosperity of our economy and communities is dependent on the political structures and mechanisms used to manage and coordinate our economic systems.”

No politician expecting to be taken seriously would say that today. State intervention was discredited long before it collapsed in the 1980s. Even our prime minister in Australia pays lip-service to “flexible markets with the right incentives and price signals to maximise the value of our people and capital resources.” But how does that square with her government’s quiet push for a more intrusive urban policy agenda?

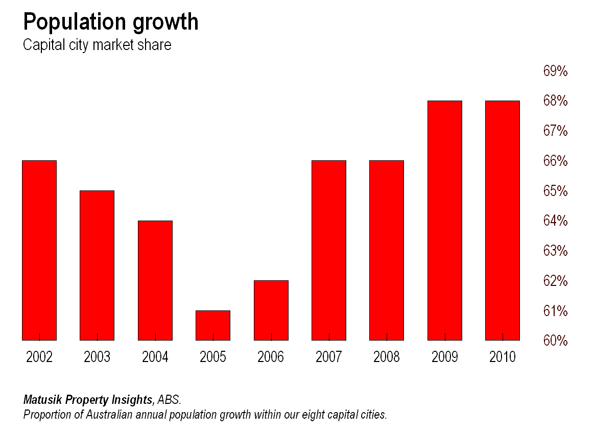

Over the last twelve months, Infrastructure Minister Anthony Albanese has been laying the ground work for a grand National Urban Policy, to be announced later in the year. To this end, he released three dense documents. Last March we got State of Australian Cities 2010 (“Cities 2010”), a compilation of statistics confirming, amongst other things, that cities account for 80 per cent of our Gross Domestic Product. Then in December came a discussion paper and a background paper, both called Our Cities.

Their general drift can be gauged from a line in the latter’s final chapter. It’s the sentence quoted at the top of this article, with the words “cities” and “urban” replacing “economy” and “economic.”

Embarrassed to champion intervention at the macro level, progressives resort to carving chunks out of the national economy and relabeling them “the environment”, “social capital” or “urban planning” before turning reality upside down. As he moves urban policy to the environment ledger, Mr. Albanese promises to transform the “productivity, sustainability and liveability” of our cities. Intervention is bad for the national economy, it seems, but good for the 80 per cent of GDP generated by cities.

Urban Myths

The authors of Mr. Albanese’s documents are anonymous, but aficionados will recognize the handiwork of Curtin University’s Sustainable Policy Institute, Griffith University’s Urban Research Program, the Faculty of the Built Environment at NSW University, and other focal-points of green orthodoxy. The reference lists are full of their output. Their technique of persuasion, recycled by Mr. Albanese’s Department, is to evoke plausible images while perpetuating three myths: suburban growth worsens carbon emissions and traffic congestion, people are being forced to live far from jobs concentrated in CBDs, and denser development will make housing cheaper.

The discussion paper says: “Australian cities generate very high carbon emissions and air pollution from our heavy reliance on carbon fuels for energy and transport. Carbon emissions from transport are principally due to the lengths of trips necessitated by our dispersed cities and our extensive use of private motor vehicles.” Variations of this passage recur throughout the documents. It sounds plausible enough. So many vehicles cris-crossing our wide open cities must be spewing out heaps of carbon dioxide. But the documents ignore evidence painting a different picture.

There is the Australian Conservation Foundation’s Consumption Atlas, which found that dense, affluent, inner-suburbs account for more carbon than the dispersed fringe, suggesting that, as a factor in emissions, general consumption trumps settlement patterns; there is a 2007 study by Randolph and Troy confirming earlier findings that energy consumption per capita in high-density developments, like high-rise apartments, is notably higher than in detached housing; there is a recent report by Allen Consulting for the Victorian Building Commission, noting the absence of conclusive evidence that vertical living is more ‘sustainable’ than conventional homes; and there is more.

None of these rate a mention in the documents. Chapter 5 of the background paper does reference a couple of studies by Alford and Whteman (2009) and Trubka, Newman and Bisborough (2010), but these focus on “transport energy consumption” and “transport greenhouse gases.” They don’t investigate the impact of urban form on general consumption, the real determinant of emission levels. And a study by Perkins et al (2009), cited in Cities 2010, actually contradicts the approved message: “overall, it cannot be assumed that centralised, higher density living will deliver per capita emission reductions for residents … ”

There is no reliable evidence that suburban growth is worse for emissions. Even Griffith’s Brendan Gleeson, a very green urbanist, had to concede that “the faith … in residential density as a simple lever that can be used to manipulate urban sustainability appears to be misplaced. New Australian scientific analysis points to the consumptive lifestyle, not the nature of one’s dwelling, as the root of environmental woes.”

In any event, transport accounts for 14 per cent of Australia’s 1.4 per cent share of global emissions, or a minuscule 0.197 per cent of the world’s carbon. We should retain a sense of perspective, even if the documents obsess about our high per capita emissions. If the climate is being affected (a big if), it’s absolute volumes that matter.

Allied to the myth of carbon-spewing suburbs is the myth of centrally-located jobs. We read in Cities 2010 that “the impacts of outward expansion and low density residential development have been a greater separation between residential areas and locations of employment …” The discussion paper asserts, more directly, that “the trend to inner-city living reflects changing preferences for dwellings and location – living closer to employment that is concentrated in central areas.” Again, similar statements crop up throughout the documents. People shouldn’t have to drive or commute long distances to a “centre” where the jobs are.

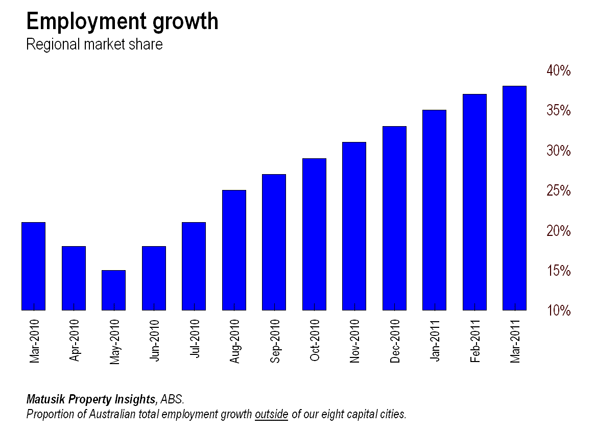

Evidence to the contrary is easy to find. According to the NSW Department of Transport, only 12 per cent of Sydney’s jobs are in the CBD, and second tier centres like North Sydney, Chatswood, Parramatta, Hustville and Penrith have no more than 1.8 per cent each. The rest are distributed throughout the metropolitan region. In the case of Melbourne, McCloskey, Birrell and Yip (2009) say it’s absurd to concentrate housing near transit lines since only 19 per cent of jobs within the Melbourne Statistical Division (MSD – Greater Melbourne) were located in the Melbourne Local Government Area (the CBD), while 81 per cent “are scattered throughout the rest of the MSD”.

In fact, the background paper points out that a majority of the employed in Sydney, Melbourne and Perth live within 10 kilometres of their workplace, while around 15 per cent live more than 20 kilometres away. This is hardly a disaster in the making. Consistently, Cities 2010 refers to “evidence that commuting distances have been stable or even declining since the 1990s in a number of capital cities.”

For green urbanists, these myths are indispensible. Their agenda hasn’t a hope unless the public accepts that suburban growth will spoil the climate, and hike congestion and transport costs. As for housing affordability, the documents take a leave-pass (social housing is another story). They promote the term “living affordability”, adding petrol prices and mortgage rates to the equation.

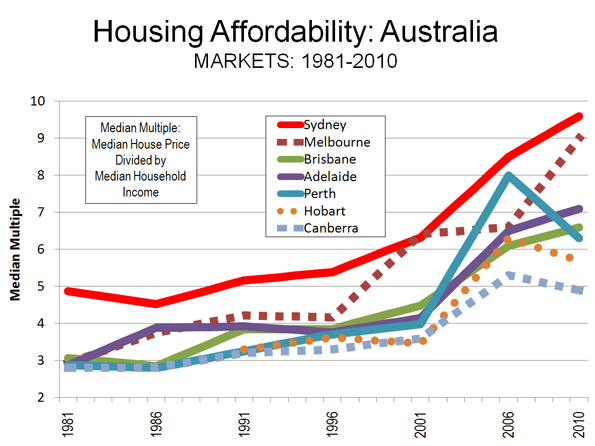

Evidence linking costly housing to supply restrictions on the fringe, like the annual Demographia survey, is too inconvenient. When the background paper does get around to the subject, it says “multiple factors [impede] the delivery of an efficient supply of suitable and affordable housing.”

These include “land zoning and building code regulations and other standards related to building quality.” A few pages later, however, canvassing some solutions to the problem, the paper proposes “reforming planning systems to … position a variety of residential development in close proximity to centres and transport infrastructure”. Doesn’t this mean a lot more inefficient “land zoning”?

This is just one instance of disjointed logic and economic illiteracy; many others are scattered throughout the documents.

The Invisible Hand and Land

Actually, cities are part of the economy, and are subject to the same principles. The operations of demand, supply and prices are equally applicable to land and structures. They can’t be erased by regulation, even if it’s called planning and zoning. The inflationary effect of coercive zoning on land values is the elephant in the room. Nowhere is it acknowledged in the documents.

Consider two recent press items. Retail tenants in Pitt Street Mall, the heart of Sydney’s CBD, are paying rents as high as $13,000 a square meter, while industrial tenants on the north-west outskirts pay around $237. These rent differentials are, of course, a function of distance, and influence the viability, not just the location, of various types of activities.

Restricting expansion and other forms of coercive zoning place an escalating floor under peripheral rents and values. Mr. Albanese’s authors fail to appreciate the implications of this, not least for “urban productivity.” There is little call to dwell on economic mechanisms if you believe, as the discussion paper puts it, “the private sector, through a myriad of individual decisions and investments, guided and constrained by government investments, regulations or charges, is a powerful shaper of cities [emphasis added]”.

In the documents, lifting productivity boils down to cutting the costs of traffic congestion, estimated to reach $20 billion a year by 2020, principally by reducing “car dependency” (another loaded term, echoing drug dependency).

Ignoring the reality of high job dispersal, the background paper says “a key challenge is to reduce dependence on motor vehicles while maintaining access between and within locations … the Australian Government recognises that it has a role … in investing in major mass transit systems, identifying and protecting new transport corridors and supporting means to shift from private vehicles to public transport”. But as McCloskey, Birrell and Yip explain, “the high level of job dispersal around Melbourne [and other cities] cannot be easily unwound.” In those conditions, Mr. Albanese’s strategy is doomed to failure.

Alternatively, when diseconomies from congestion start to outweigh economies from centrality, firms and commuters will move to other, less congested sites, easing congestion all-round. This is the only effective, long-term solution to congestion. However by mandating concentration rather than enabling dispersion, evidenced by a dim view of road-building, green planning stymies this process. The documents want to end it altogether.

According to the background paper, “connectivity within cities can also be achieved by placing people closer to the jobs, facilities, goods and services they desire – or putting these closer to where people live. This highlights the important role of integrated land-use and infrastructure planning in managing the need for physical travel”. But this notion, that firms and residences can be “placed” by a central authority, is logically flawed. It suffers from something akin to a “coordination problem” (a concept from game theory).

Suppose household A has, in existing circumstances, chosen its optimal location relative to (1) affordable housing, (2) employment and (3) services. How can the government arrange things so that A ends up in a more optimal location? Moving A closer to work may push it further from affordable housing and services. Moved closer to services, A may end up further from other factors, and so on. It’s unlikely that the government can ever place A in a better location relative to all three factors.

Then suppose household B has chosen its own optimal location relative to the three factors, some distance away from the point chosen by A. How does the government improve the outcome for both households? Action benefiting A may hurt B and vice versa.

The same problem can be framed for businesses locating relative to (1) competitive rents, (2) transport routes, (3) suppliers, (4) suitable labour and (5) customers (market). Our cities host hundreds of thousands of households and businesses. There is no way that a planning hierarchy can engineer a more efficient outcome than the people themselves, interacting freely in the marketplace. Official meddling is more likely to induce problems than solve them.

Instances of disjointed logic abound. One paper talks about “micro-reforms to reduce costs to businesses and consumers”, but another urges “access to a range of [more expensive and less efficient] high-quality renewable energy sources”; a paper commends “the principle of subsidiarity, ensuring that the most local level of government is used …”, but then calls for “improving alignment and integration of planning and investment across all three levels of government to support the nationally agreed … objective”; a paper demands action to “reduce red tape”, but all three documents offer heaps more instruments and regulations.

Ultimately, Mr. Albanese’s documents are the pretext for a new wave of intrusion into economic life. As such, they represent a glaring case of bureaucratic overreach. However much he may spruik flats, smaller houses, public transport and higher utility bills as an enhancement of urban “liveability”, most Australians will disdain them as anything but liveable.

John Muscat is a co-editor of The New City, where this piece originally appeared.

Photo by Joseph Younis.