Southern California, like the rest of America and, indeed, the higher-income world, is getting older, rapidly. Even as the region’s population is growing slowly, its ranks of seniors – people age 65 and older – is exploding. Since 2000, the Los Angeles metropolitan area population has grown by 6 percent, but its senior population swelled by 31 percent.

The trend is stronger in the Inland Empire, where senior growth was almost 50 percent, the 14th-highest among the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan areas and more than three times the national average.

Figures from the Census Bureau suggest that these trends have continued since 2010. Regionwide – Ventura, Orange, San Bernardino, Riverside and Los Angeles counties – the senior population has surged 9.7 percent, more than the national rate of 8.4 percent. Overall, the senior share of the Los Angeles metropolitan-area population has increased to among the 20 largest in the nation.

These aging trends reflect in many ways the economic torpor of the region over the past decade. “We could be at the end of the period where Los Angeles thrived as a destination of choice for the working-age population, and it may simply begin to age, much like our counterparts in the Northeast,” suggests Ali Modarres, a former Cal State Los Angeles professor who now heads the urban studies center at the University of Washington, Tacoma. “Is L.A. finally out of its ‘sunbelt’ phase and entering its graying era?”

Less movement

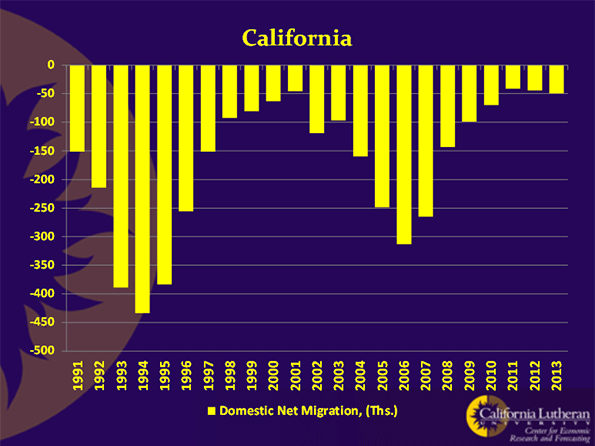

Once, Modarres notes, this region was – like Florida and Arizona – a major lure to retirees, due largely to its ideal climate. But as the region has become more expensive and congested, this appeal has diminished considerably. As a result, our graying is likely the result not so much of senior migration into the region – since the L.A. area is the nation’s second-largest, after New York, exporter of people – but a case of people getting older in place.

In 1980, notes USC demographer Dowell Myers, half of the Los Angeles population ages 55-64 had migrated from another state. By 2010, that inbound segment had dropped to 26 percent and, by 2030, he projects, only 14 percent will be from elsewhere.

Traditionally a source of youthfulness, immigrants, too, are getting older. In Los Angeles County, the foreign-born share of the 55-64 population has risen from 30 percent in 1990 to 50 percent in 2010. By 2030, some 60 percent of this population will be foreign-born. Given the slowing rate of new immigration, Myers and others suggest that the foreign-born population will drop among the younger cohorts over the next few decades.

Geographic divide

Like everything else in this increasingly bifurcated metropolis, the geography of aging is divided into two main segments – high-income growth around the coast and lower-income, more minority-oriented sections further inland. In both groups, evidence suggests that they tend to generally stay close to home. Across the country, baby boomers, who are becoming seniors in ever-larger numbers – notes a recent Fannie Mae report – generally prefer staying in the homes they have occupied for years.

An examination of data from the 2010 census mirrors these trends. Some of the largest increases in seniors occurred in such heavily Latino and working-class areas as the Coachella Valley, where the 65-plus population soared by 14,700, or 43.2 percent; the Ontario area, where it grew by 30.3 percent; and Santa Ana-Anaheim, where this population expanded by 27.1 percent.

This pattern seems to be holding up since 2010, at least at the county level. By far the largest increase in seniors has occurred in the Inland Empire, which saw its senior population rise by 63,000 people from 2010-13. Overall, both San Bernardino (15.1 percent growth) and Riverside (13.8 percent) counties expanded their senior populations well above the regional average of 12.6 percent.

Coastal clusters

Looking at the 2010 Census, we see another fascinating pattern – the aging of beach communities, long the center of the Southern California youth culture. Indeed, the biggest increase in seniors over the past decade took place in coastal Orange County, where the senior population grew by 25,600, or a remarkable 50 percent. At the same time, the oldest parts of the Southland are also by the ocean, in Santa Monica and the Westside of Los Angeles. In 2010, roughly 14 percent of residents of this generally affluent area were seniors, versus 11 percent for the rest of the region.

Why are seniors staying in these enclaves? Well, the real question is, why not? Seniors who have stayed put, for the most part, were able to buy their homes for what today would be almost impossibly low costs, even though they were more expensive than average at the time. But, over the past three decades, as house prices have exploded across Southern California, these areas have become proportionally more unaffordable, which accounts for their declining populations of children as well as young families.

Safely ensconced with little or no mortgage debt, and with their property taxes limited by Proposition 13, many of these lucky seniors get to enjoy the fair climate and gorgeous beachfront for the rest of their active lives. Needless to say, few younger people, particularly families, will be able to join the party for quite a while.

Southland implications

Aging is a natural process, and virtually every city in the world, particularly in higher-income countries, now feels its effects. But the key issue is one of relativity. Until recently, this region’s populace was generally much younger than the national average but, since 2000, has seen its median age rise at nearly twice the national rate. Now, it could be on the way to resembling a sun-baked version of a Rust Belt community, as net outmigration continues by younger people, families and even immigrants.

There arguably are some good aspects of being in an aging region, such as lower demand for schools and, often, lower crime rates. In addition, seniors are an increasingly important source of consumer demand – according to Nielsen, Americans over age 50 by 2017 will control some 70 percent of the nation’s disposable income. Seniors, notes the Kaufmann Foundation, are also the fastest-growing entrepreneurial population, critical for future job creation.

Of course, there are dangers in taking these trends too far. Over time, young people and families are critical to creating demand for many key products, notably houses, cars and furnishings. They also are more likely to start and staff innovative companies. A declining youth population is not necessarily a good thing in a region that lives off being on, and establishing, the cutting edge of design, entertainment and technology.

There’s nothing inevitable about the region becoming a giant retirement home. The Southland can again become a magnet for migration. It’s advantages are manifest, with the beaches, mountains and incomparable weather. But the past couple of decades have demonstrated that these inducements alone are not enough to keep millions of people from moving away.

We need to start addressing the causes for persistent out-migration, and, more importantly, the relative dearth of new people. There are obvious candidates for remediation – one of the nation’s highest costs of living, particularly for housing, too many poor schools, a challenging business climate and a declining infrastructure. These are helping to drive the younger generations and enterprises – who should want to flock here – to Nevada, other mountain states, Texas and elsewhere.

This piece first appeared at the Orange County Register.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

“Senior Citizens Crossing” photo by Flickr user auntjojo.